When opera singer Emily Geller was growing up in Manhasset on Long Island, the parts she really wanted to play in the school musical weren’t coming her way.

“I was always cast in the chorus,” she said.

That frustration bolstered her determination to wrest control of her future away from naysayers and forge her own path to center stage. “I wasn’t born with a good voice,” she said. “Teachers didn’t know what to do with me.”

So, she went out and found someone who did. “Once I had a teacher that really believed in me, things changed,” she said. Then in high school, Geller was accepted into Boston University’s Tanglewood Institute for vocal students, a pivotal program that confirmed her trajectory.

Now, praised by critics as “an effervescent delight,” and “delightfully over the top,” Geller has made her mark as a mezzo-soprano, performing in operas up and down the East Coast.

Lately, Geller, a resident of Briarcliff Manor, has been playing roles coveted by so many aspiring singers, from Annina in “La Traviata” to Mercedes in “Carmen” or Suzuki in “Madama Butterfly.”

In retrospect, her journey to those roles couldn’t have happened any other way.

“Neither of my parents are musical,” she said. “But I was very involved in theater and chorus.” She knew the stage was where she wanted to be. I started out acting first, then evolved into musicals. You only start learning opera when you’re older. Once you get to college you start training on arias. But musical theater and opera are pretty different.

“The kind of technique you need to sing over a full orchestra with no microphones is completely different. Your body is your instrument,” she said of opera, “Some people are born with larger instruments.” She’s quick to add that weight has nothing to do with the size. What matters are genetic traits like the size of the larynx, vocal folds and the length of vocal tract.

“It’s the technique of voice,” she added. “You can change your technique. Once I learned the correct technique in how to sing, I got better really quickly.”

For her, opera is an athletic endeavor.

“I would compare singing to any sport,” she said. “There’s lots of different drills, a lot of things you work on individually and then put it all together.” Geller stresses the importance of good support, being resonant, being able to tell a good story, singing at dynamic levels and making sure diction is clear. “Being a professional opera singer is like the Olympics for singing,” she said. “You train for decades. I am still learning to sing.”

That’s one reason she can relate so well to her high school students. She sees her role as a voice teacher as critical to not letting great talent slip between the cracks. She remembers that it was when she changed voice teachers that she got “significantly better.”

What did the teacher do differently?

“It wasn’t just one piece of advice,” she said. Voice teachers get good results by not giving up on their students. Not in a cheesy, believe in yourself kind of way. But in that initial moment when progress is slow. A lot of teachers give up.

“The ones that had a beneficial effect kept trying different exercises when the first ones didn’t get results. The teacher she stuck with never gave up on her going to the next plane, even after she didn’t respond or do it right the first time.

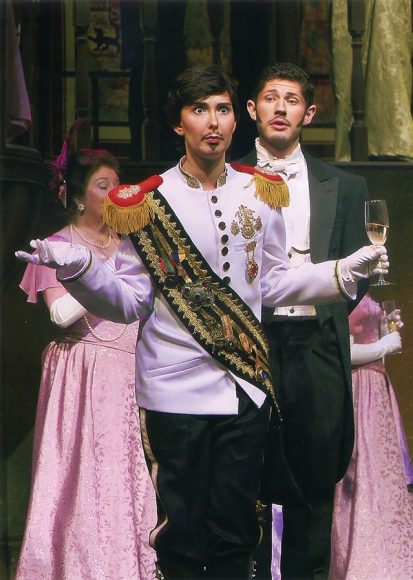

Because of her vocal range as well as her acting chops, Geller often plays “pants roles,” that of young male characters. “Those are usually played by lower female voices,” she said of contraltos and mezzos. “I have been cast in a lot of comedy roles,” she added. “People seem to like it so I just keep doing it.”

Geller takes a sensible approach to caring for her voice onstage and off. “If you’re singing technically correctly with low, supported, resonant sound, it’s not necessarily putting a lot of strain on your voice,” she said. “But if you’re singing over a long period of time, your voice can get tired.”

You won’t find her going mute for long stretches or gargling with warm salt water. “Usually, opera singers are pretty hardy,” she said. “I just get a good night’s sleep, stay hydrated and just listen to my body.” She will try not to yell if ever in a loud environment, though. Her trick is to bring earplugs. “They allow me to hear myself speak.”

Any other routines before Geller takes the stage?

“I wish I could say something really cool,” she said. “A lot of singers have super-fun routines. I like to drink coffee before I sing…but maybe that’s just because I like coffee.

“I do bring my score with me backstage,” she added, “even though I have everything memorized backwards and forwards.” Directors can always give last-minute notes.

Is there a particular part she would love to play in the future?

“I would love to say something that’s a real standard role,” she said. “I think an obvious answer would be Carmen” — actually a soprano role that’s been a showcase for mezzos because of its darker tessitura. But that’s not the answer she’s leaning toward. “I’m interested in new, modern operas,” she said. “A lot of companies do ‘Rigoletto’ by Verdi,” she said. “Maddalena is a role (in it) I really want to do. So that would be the short answer.”

And which opera has moved her to tears?

“When it’s done really well, ‘Madama Butterfly’ makes me cry,” she said. And earlier this year, she saw “Fellow Travelers,” about a gay love affair set against the backdrop of 1950s Washington, D.C., and the Sen. Joseph McCarthy Communist witch hunt. That, she said, was “the most I’ve ever cried at an opera.”

“But I don’t cry when I’m onstage,” she said. “As a performer, I’ve never cried.”