On Oct. 1, Beijing will celebrate the 68th anniversary of the defeat of Chiang Kai-shek in the Chinese civil war and the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

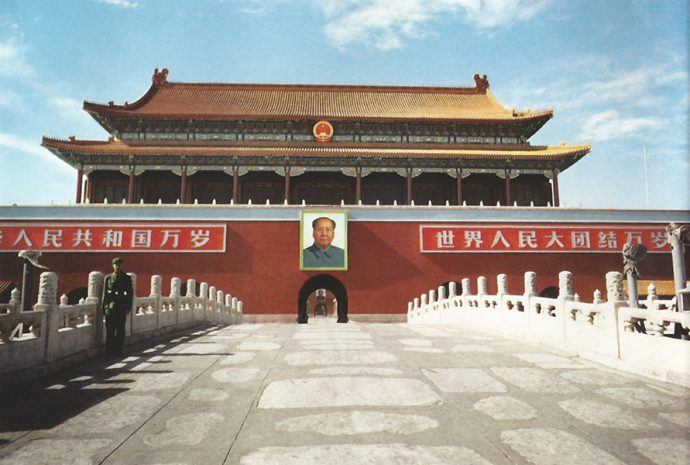

National Day is usually marked with a giant military parade through Tiananmen Square under a large portrait of Mao Zedong, who led the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) across the Yangtze River for the capture of Nanking (now Nanjing), Chiang’s capital. This year’s National Day has special significance since it comes at a time when China is competing with the United States for global leadership in economic and military development.

Since coming to power in 2012, President Xi Jinping has been seeking to heighten the nationalism and pride of the Chinese people in their cultural and political history. His current “China Dream” envisions a “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), which my wife, Audrey, has written about in WAG and which would, under Chinese leadership, launch a global infrastructure program dubbed “the New Silk Road.” It is in fact an expansion of Mao’s vision of the People’s Republic of China, which was realized when the PLA took over Chiang’s Nationalist capital, the key to Mao’s eventual control of the entire Chinese mainland six months later.

As a correspondent for the Associated Press, I covered the fall of Nanking. At dawn on April 23, 1949, I was awakened by the sounds of explosions on the Nanking riverfront. Communist troops were storming across the Yangtze in all manner of boats under the cover of artillery fire. I clambered into my jeep and headed toward the river quays. Mobs in the streets were looting houses. Chiang Kai-shek’s government had fled to Canton, the southern metropolis, and the luxurious houses of officials were being stripped. The sky was brightened by flames of burning government buildings, including the massive Judicial Yuan. Saboteurs had been at work.

On the highways, the military checkpoints were unmanned and I soon learned that the Nationalist garrison had abandoned the city and the municipal police had fled with them. Thousands of refugees and disheveled Nationalist soldiers were fleeing south. The river port was ablaze with torched buildings and exploding fuel dumps.

In the American Embassy, young diplomats patrolled the grounds with flashlights. A platoon of Marines had been stationed in the compound but had been flown out on April 20 to Shanghai to avoid possible clashes with the Communists. Six Marines were left behind to protect the 200 embassy personnel.

At 6 p.m., I picked up Bill Kuan, a Chinese reporter, who worked for the Agence France Presse. After inspecting the airfields, which we found wrecked, we headed for the Nanking Hotel to find the Peace Preservation Committee, appointed to hand over the city to the Communists to minimize damage in the takeover. Committee members said that they had made contact with the Communists and delegates would meet their advancing troops.

Hoping to meet the Communists I drove slowly toward the Northwest Gate at 3 a.m. Suddenly, I heard a command to halt. Two soldiers with rifles pointing at us emerged from the shrubbery beside the road. They were the point soldiers of the first column of Gen. Chen Yi’s Communist troops, ordered on forced march to enter Nanking. The officer, who was to meet the Peace Preservation Committee questioned Kuan and me, then ordered us at gunpoint back into the city.

I drove my Jeep back into Nanking, past the burning Judicial Yuan to the city telegraph office. There Kuan and I flipped a coin to determine who would file first. Kuan won and sent a three-word flash: “Reds Take Nanking.” My 65-word dispatch followed. Immediately after my transmission, Communist troops cut the landline between Nanking and Shanghai. When Kuan’s dispatch reached the foreign desk in Paris, the editors waited for additional detail but radio transmission was out until morning. The delay denied Kuan a world beat and bestowed it on me. My dispatch went out immediately on the AP wires. Through the years, Chinese websites have carried a photograph of Mao Zedong reading the front page of a Peking newspaper citing my dispatch on the Communist seizure of Nanking.

At daybreak I picked up Chester Ronning, charge d’affairs of the Canadian Embassy, and we drove to the Northwest Gate where we witnessed the entry of thousands of Communist troops into the city. I had met his daughter Audrey in the Chinese capital when she was attending Nanking University. We had become engaged, but at this point she had been evacuated with her mother and siblings to Tokyo with other diplomatic families as the Communists closed in on Nanking.

At first, I was imprisoned by the Communists, who thought my typewriter meant I was a spy. Two weeks later, I was freed and spent the next six months reporting from Communist-occupied Nanking. After Mao’s establishment of The People’s Republic of China, I flew to Audrey’s home in Camrose, Alberta, where we were married.

We returned to Hong Kong, which became our base for reporting on Mao’s complete control of the Chinese mainland. It remains to be seen if Xi will enjoy success with his “New Silk Road” or, like Mao, enjoy initial success but then stumble and suffer the kind of violent reversals that overwhelmed Mao and the country in the disastrous Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.