Edmund F. Ward’S works depicting White Plains history captured a key aspect of the city that is the seat of Westchester County government.

In 1926, Ward painted the Revolutionary War “Battle of White Plains” to be used for a commemorative stamp. Selected by White Plains Congressman J. Mayhew Wainwright (of Wainwright House fame), Ward’s design was sent to the United States Treasury and turned into a two-cent stamp (sheets of which can sell for more than $1,000 today). More than 43 million of these stamps were sold (the first of which was purchased by Ward’s wife, Laura).

A few years later, Ward completed a larger oil painting of the “Battle of White Plains,” which was purchased by the city and hung in its post office. In 1984, the painting was moved to the White Plains Public Library and is now on display high on the walls of the east wing.

Born and raised in White Plains, Ward was a 1910 graduate of White Plains High School, where he worked for The Orange, the school’s newspaper, and illustrated for the yearbook. After graduating, he took a job on the railroad before working for a Kensico Dam surveying team. His passion, however, was art.

“I had the idea I wanted to paint pictures,” he once said. “I can’t remember when I didn’t want to make pictures. It was just built in me, nothing else would do.” So, with the money made from his civil engineering jobs to cover his commuting costs, he enrolled at the Art Students League in Manhattan where he met Rockwell. The two became fast friends and shared a $15-a-month studio which was, unbeknown to them, above a brothel. Before his 20th birthday, Ward had already begun illustrating for The Saturday Evening Post, alongside Rockwell yet again.

Ward spent much of his early career illustrating magazines such as The Post, Harper’s, Woman’s Home Companion, Redbook and Cosmopolitan. Many of his illustrations, like those of other illustrators of the time, have disappeared since their publication. “The art directors for the advertising agencies would grab off the good stuff,” Ward said.

To his dismay, the painting for which he may be best-known is commonly referred to as “Hamilton at the Cannon,” as many viewers incorrectly identified the man at the cannon as America’s first secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton. Historians note that although Hamilton, George Washington’s aide de camp, did command artillery on Chatterton Hill during the 1776 Battle of White Plains, none of the figures in Ward’s painting are pictured in the captain’s uniform that Hamilton wore. “I didn’t paint Hamilton. I didn’t want Hamilton,” Ward said, insisting he intended to depict a humble gun crew.

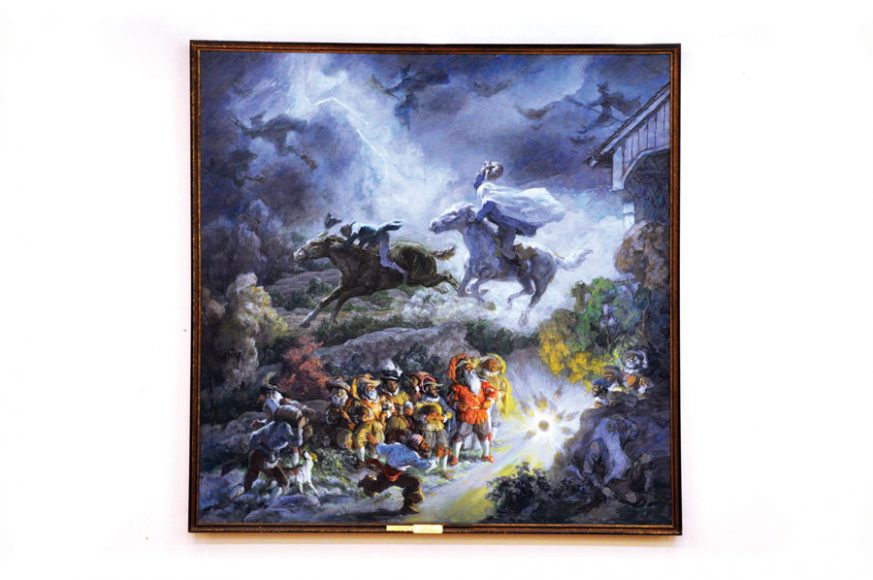

One of his favorite works was his “Hudson Valley Legends,” now also in the east wing of the White Plains Public Library. The painting, which won the Bicentennial Award at the National Art Show of the Hudson Valley Art Association in 1976, combines images of Washington Irving’s “The Legend of the Sleepy Hollow“ and “Rip Van Winkle,” fueling the imagination of each passerby.

Although his works were shown at major galleries and have toured the nation, garnering their share of awards, Ward would observe that Rockwell, “made millions, while I haven’t.”

Nevertheless, Ward never gave up on his passion. After moving away from magazine illustrations, he taught art at Westchester County Center and the Art Students League. Ward continued to paint, shifting from illustrations to portraits of prominent men in the White Plains area and other commissioned work. He became active in the local government after illustrating for the Republican Party. Ward claimed he didn’t believe in retirement and spent the majority of his later years working in his studio.

Even when he traveled, he carried a sketchbook, canvas and paints with him. “When you go out looking for a paintable scene, you will seldom find it, for you keep thinking beyond each bend there will be a better picture,” he said. Ward’s passion for art truly carried throughout his whole life.

“Art is a necessary aid to living,” Ward once observed. “It should inspire enthusiasm and other emotions. The Abstract Expressionist and the like are capable of fine craft and design, but they aren’t dealing in everyday symbols that can be understood. They evoke more bewilderment than enthusiasm. But then, I really can’t express my true feelings about art in words. If I could, I’d be writing, not painting.”

When he died in 1990, just a few days short of his 99th birthday, Ward was hailed for the way he shaped the city that in turn shaped him.

“He was so much a part of White Plains,” said former city historian Renada Hoffman. “He has accomplished so many things other than just painting. He was part of our background and our heritage.”