“…the New Frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises — it is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer to the American people, but what I intend to ask of them. It appeals to their pride, not to their pocketbook — it holds out the promise of more sacrifice instead of more security. But I tell you the New Frontier is here whether we seek it or not.” – John F. Kennedy accepting the Democratic Party nomination for president of the United States, 1960

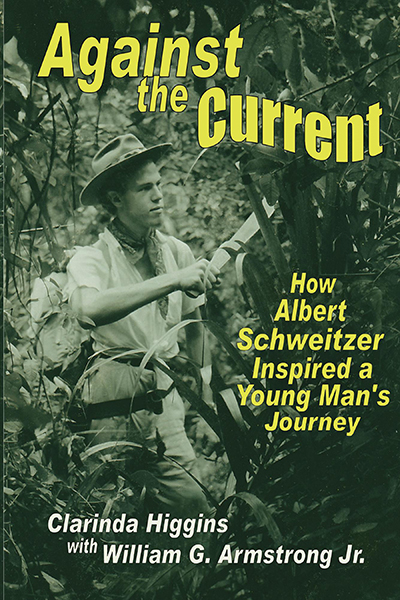

On May 27, 1959, a young American anticipated John F. Kennedy’s call to action, arriving at The Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon, to begin a life of sacrifice and service. The 18-year-old from North Brookfield, Massachusetts, learned how to wield a machete to prune the encroaching jungle, particularly along the path to the leper village. He helped plant a 15-acre riverside garden filled with eggplants, beans, peppers, beets, tomatoes, lettuce, carrots, turnips, cabbages and kohlrabies, cousins to the cabbage. He forged bonds with creatures of the two- and four-legged variety, marveling at the goats, sheep, wild pigs, chickens, ducks and pigeons that had the run of the complex, along with the butterflies, blue fish catchers, African red parrots and toucans in the jungle skies beyond.

In time, he would conduct a cardiology field study that would save lives among the Fang people, who suffered from a correctible condition called mitral stenosis. A little more than a year later, however, he set off across Africa toward his ultimate goal of living in Israel.

He never made it, meeting a grisly fate in the newly independent, strife-torn Democratic Republic of Congo. That is where Mark Higgins’ life ended. But, in a sense, it’s where his story begins.

“It’s a sad ending, but the consequence is an inspirational legacy,” says William G. “Bill” Armstrong Jr. He and his wife, educator Clarinda Higgins, Westport residents, are seated in l’escale restaurant bar at the Delamar Greenwich Harbor, discussing their haunting book about Mark’s brief but transformative life, “Against the Current: How Albert Schweitzer Inspired a Young Man’s Journey” (Oakham Press, 2014). Mark and Clarinda, nicknamed Rindy, were first cousins and Rindy, a warm, enthusiastic woman who teaches in Weston and Westport, recalls a tall (6-foot, 5-inch), grave young man with whom she shared a special connection.

Shaking his hand when his family came to visit in the manner of a child who wants to be grown up, 9-year-old Rindy looked up at him — and to him.

“There was some recognition in his eyes,” she recalls. “And I would always say, ‘When I grow up, I want to have large hands like cousin Mark. And I have big hands,” she adds, splaying her fingers.

That wasn’t all Rindy noticed. “Mark was always very morose, gloomy,” she says. Of the three siblings, “he was the most affected by his parents splitting up.”

His depression, however, went beyond that. The Higgins’ name in Worcester, Massachusetts, was synonymous with achievement. Mark and Rindy’s grandfather, John Woodman Higgins, possessed a playfulness that delighted his grandchildren but belied a shrewd business brain that built Worcester Pressed Steel and amassed the nation’s finest collection of arms and armor, which became the now-defunct Higgins Armory Museum. Mark’s father, Carter, inherited his father’s drive but not the playfulness. Mark’s older brother, Dick, took himself off to Greenwich Village where he became an avant-garde poet and artist and co-founder of the interdisciplinary Fluxus movement, working with composer John Cage and artist Yoko Ono.

It looked, then, as if the steely Higgins’ mantle would fall on the lanky Mark’s shoulders. But who we are is in part what we are not. Mark had no interest in becoming a third-generation industrialist. The crushing pressure he felt to conform led him to attempt suicide with an overdose of sleeping pills while he was a senior at Milton Academy and endure a horrific stint at The Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut, where the patients undergoing the standard electroshock therapy had included the actress Gene Tierney.

Salvation came in the form of Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) — theologian, organist, medical missionary and Nobel laureate, whose “reverence for life” credo would galvanize members of the Higgins’ family.

“His reverence for life extended to every living thing,” Rindy says. “He’d even stop the truck for ants…. I really adopted it for myself. Schweitzer was my hero. I read everything I could about him.”

Adds Bill: “We can apply that philosophy to everything we do and it really changes people.”

In offering his services to Schweitzer, however, Mark had traded one exacting father figure for another, Rindy says. Was that perhaps why he was eager to push on to the Congo, despite Schweitzer’s admonition not to? The young man was determined to fulfill his dream of communal life in a kibbutz. But in the Congo, where resentful locals squared off with Belgian forces intent on protecting their nationals, Mark was mistaken for a European colonial and shot to death on July 25, 1960, his remains then mutilated.

News of the “missing” American made headlines back home, reaching the attention of a man embarked on a bid for the nation’s highest office. How many, John F. Kennedy asked at a University of Michigan rally that October, were willing to serve at home and abroad?

While no one knows where Kennedy got the idea for the Peace Corps, Bill says, it seems reasonable to conclude that it came in part from Mark’s example.

When Kennedy established the Peace Corps on March 1, 1961, he named his brother-in-law Sargent Shriver as its first director. In a not-so-quirk of fate, Shriver had been a fraternity brother of Mark’s father at Yale University.

“Those kind of coincidences kept us going,” Bill says about researching and writing the book, as did an encounter in Redding with medium Roland M. Comtois, who kept coming back to Rindy in the audience, saying he had a message for her from beyond. Finally, he revealed it: “You must finish the book.”

She and Bill had met in 2004, married in 2007 and worked on the book for a year and a half, from 2012 to ’14.

“Bill’s research skills were a great help,” Rindy says of her husband, who has had a long career in journalism, public relations and academia.

Working on the book together and traveling to Gabon, where The Schweitzer Hospital has become a museum, brought them closer together. Schweitzer’s legacy also embraces The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship, of which Bill is a director, and The Albert Schweitzer Institute at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut.

As for Mark’s legacy, Rindy says it’s about “not being afraid of your inner self. It’s all about the journey of self-discovery.”

“He lived a life that’s remembered by so many people,” Bill says. “He made such an impact….In part, he was the inspiration for the Peace Corps and, if that’s not a fitting legacy, I don’t know what is.”

For more, visit schweitzerfellowship.org, qu.edu/on-campus/institutes-

centers/albert-schweitzer-institute.html and oakhampress-againstthecurrent.com.