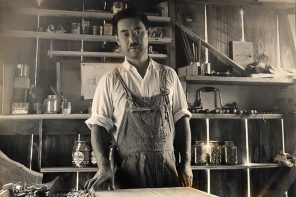

Paul Evans (1931-87), along with George Nakashima and Harry Bertoia, is internationally recognized as one of the superstars of the postwar Delaware Valley American Craft Movement.

Today, Evans’ creations are among the brightest lights in the American furniture market, with the most valuable of his unique cabinets realizing nearly $400,000 at auction. And while Evans trained in the craft tradition, he was also a prolific commercial designer, creating furniture collections that were highly sought after in the 1960s and ’70s, trading regularly in the auction market today.

New Jersey-born Evans studied design and metalsmithing at the School for American Craftsmen (SAC) at Rochester Institute of Technology and the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. A brief tenure as a metalsmith at Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, led in 1955 to a decade-long collaboration with the studio furniture designer Phillip Lloyd Powell. The two shared a showroom in New Hope, Pennsylvania, and worked both independently and collaboratively. It was Powell who encouraged Evans to apply his metalworking skills to furniture. Evans began to weld copper, iron and brass to create sculptures, a line of accessories (such as wood and brass menorahs) and furniture that incorporated wood and metal.

Over time, wood became a less prominent medium for this “carpenter in steel.” In Evans’ mid-’60s cabinets and screens, plywood bases were encased in sheets of copper or bronzed steel, which were then treated with colored pigments and patinated or darkened by a blowtorch. Finally, gold leaf and decorative elements were often added. Among the most striking and sought-after cabinets are those that feature polychromed compartments with welded elements, somewhat reminiscent of Louise Nevelson’s compartmentalized wall pieces.

Evans employed a number of trusted craftsmen to execute these works and over time this model expanded as his business grew. While he continued to produce studio pieces, he began in 1964 to work with Directional Furniture Co. in North Carolina. This successful arrangement lasted 15 years. At its peak in the mid-’70s, Evans’ firm grew to 88 employees, sending 150 to 200 pieces to New York twice weekly.

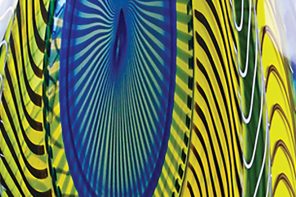

For Directional, Evans produced furniture lines that featured distinct metal finishes. In 1965, he introduced the sculpted bronze technique, best described as a Brutalist look that one might imagine equally well at home in an intergalactic interior. In sculpted bronze, a plywood carcass was built up and sculpted with a mixture of epoxy resin and sand to create a surface in bold relief. A pneumatic spray gun delivered a coating of bronze, resulting in furniture that was metallic in look, yet lightweight. Evans’ Argente technique used welded aluminum, which was treated and etched to create areas of dark and light, a look wholly different from the matte finish typically associated with aluminum.

In the 1970s, Evans turned to reflective surfaces in his “Cityscape” series, using chrome and steel first in flat and later angled configurations — a look that was perfectly suited to the disco era. Other lines followed yearly — wood to contrast metal, lacquer and striped metal, poured concrete and stainless steel with suede.

After Evans’ arrangement with Directional Furniture ended in 1979, his work turned in another direction with “electronic furniture” — tables that changed heights, cabinets that rotated and shelves that popped up and down. The venture was unsuccessful, and Evans was forced to close his business, only to die of a heart attack on his first day of his retirement.

His work subsequently fell completely from fashion but was rediscovered and promoted at the end of the last century. Evans has been the subject of several monographs, documentaries and a retrospective at the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

My boss David Rago, who has been instrumental in bringing many Evans pieces to auction, says “right now there are more high points than low ones as Evans’ work, especially from his studio period, is attracting many European collectors. The heat is definitely more on the earlier studio work, though the Directional Furniture has its share of collectors as well.”

Directional pieces are commonly found at auction, selling in the hundreds to more than $50,000 for an exceptional wall-mounted Disc Bar in sculpted bronze. But it is his studio pieces that are catnip to designers and collectors — Lenny Kravitz, Diane von Furstenberg and Peter Brandt among them — and that often bring stratospheric results.

For further reading: “Paul Evans: Crossing Boundaries and Crafting Modernism” (2014), edited by Constance Kimmerle. Contact Jenny at jenny@ragoarts.com or 917-745-2730.