There have been the ever-popular Tudors, the tabloid-ready Windsors and the tragic Romanovs. But it’s fair to say there’s never been a royal family like the Plantagenets (plan-TA-ghah-nets).

The men were brilliant; the women were beautiful.

The women were brilliant; the men were beautiful.

For more than 300 years — from the ascension of Henry II to the English throne in 1154 to the death of Richard III in 1485 — they conquered and consolidated, thundered and plundered, quested and lusted, fighting their enemies and especially themselves.

Their names and associations are legendary — Becket, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Lionheart, the Black Prince, Agincourt, the Princes in the Tower — woven into histories along with fiction by Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Jean Anouilh, Thomas B. Costain, James Goldman and Sharon Kay Penman.

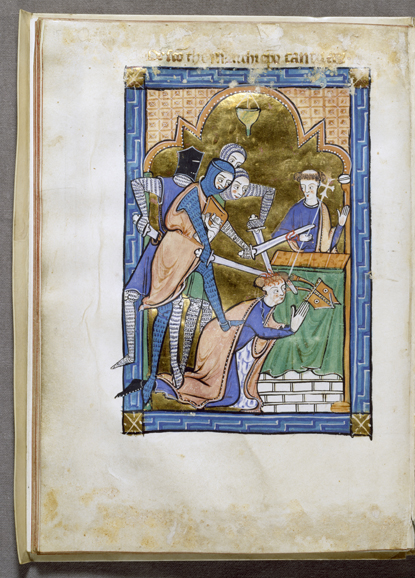

And to think this juicy family tree sprang from a dry plant or “sprig of broom” (Plante Genest) that Geoffrey V, count of Anjou, liked to wear in his bonnet. (That’s right: England’s greatest dynasty had its origins in France.) Geoffrey married the Empress Mathilda, heiress of Henry I of England. Mathilda and Geoffrey’s child became Henry II — king of England, count of Anjou and Nantes, duke of Normandy, lord of Ireland and ruler of Scotland, Wales and Brittany. A larger-than-life figure absorbed in maintaining and expanding the holdings of his grandfather and namesake, Henry battled his pal and chancellor Thomas à Becket once he made him archbishop of Canterbury, forgetting that the job really does make the man. Their maneuvering would result in Becket’s martyrdom and sainthood.

Henry’s other mighty opposite on the chessboard of life was his incandescent wife, Eleanor — duchess of the rich, romantic French province of Aquitaine and the former wife of Louis VII of France.

Even though she had borne Louis two daughters, Eleanor was able to obtain a papal annulment on the grounds that she had given him no sons and was distantly related to him. She promptly married Henry, 11 years younger and a third cousin. But then, Eleanor — who had accompanied the pious, in-over-his-head Louis on the Second Crusade to Jerusalem — was not the kind of woman to be refused. Henry would discover this again and again as they fought over their eight children — five boys and three girls — and the disposition of their realm among them, with Eleanor often taking her sons’ part against her husband. William, named for the Norman conqueror of England, died in infancy. Henry, prince of Wales and daddy’s favorite, was actually proclaimed the Young King in his father’s lifetime, which only fueled the rebellious ambitions that died with him. It would be Eleanor’s pride and joy, Richard — the dashing Crusader known as “the Lionheart” — who succeeded Henry II. Richard, however, was so bound up with military interests outside England that Eleanor would actually rule in his absence, trying to keep the Lionheart’s backstabbing baby bro, John, who aspired to the throne, at bay.

In the end, John got his wish, succeeding his childless brother. But he proved to be no charismatic Richard and was forced to concede lands to his rival, Philip II of France, and considerable power to his own barons in the document known as the Magna Carta.

By then a pattern had emerged of strong kings followed by weak or childless ones, creating a power vacuum. It would not be John’s son, Henry III, but his grandson, the tall, intimidating Edward I (“Longshanks”) who re-established the centrality of the monarchy, subduing the Welsh and engaging in an ongoing war with Scotland that he left to a son, Edward II, most unsuited to the task. Preferring everyday pursuits like gardening, this Edward remains one of England’s most controversial monarchs, not for the disastrous favoritism he bestowed on his soulmate Piers Gaveston but for its equation with a kind of fey homosexuality (most notably in Mel Gibson’s historically inaccurate film, “Braveheart.”) Whether or not Edward II was bisexual, it was political favoritism, not sexual identity, that led to his deposition and death at the hands of his increasingly unhappy wife, Isabella of France, and her lover, Roger Mortimer.

But Edward would be avenged by his son, Edward III, who quickly dispensed with Mortimer and expanded England’s power during a popular reign of 50 years. And it looked as if that popularity would continue under his eldest son, Edward, the Black Prince, an imposing military leader in the Lionheart mold. He, however, took ill on one of his campaigns, leaving his succession in the hand of his young son, Richard II, whose lofty view of absolute monarchy and favoritism — shades of Edward II — would lead to his deposition by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke and subsequent death.

This Henry — the fourth of that name to rule England — would give his country one of its greatest rulers, Henry V, whose stunning victory against a much larger French force at Agincourt and marriage to the French princess, Catherine, would cement his fame and presumably the united thrones of England and France for his son, Henry VI. However, Henry VI suffered a mental breakdown that ushered in the War of the Roses between his own Lancastrian branch of the Plantagenets and the Yorkist branch of the family.

The House of York triumphed and Edward, son of Richard, the third duke of York, ascended the throne as Edward IV. Here the Plantagenet curse of murderous ambition — visited upon father and son, brothers and cousins – would play itself out for the last time as Edward’s brother Richard imprisoned the king’s sons (the children Edward V and Richard, Duke of York) and succeeded his brother as Richard III.

Did Richard actually murder the two “Princes in the Tower,” as they came to be known? There is no concrete evidence, but he did depose and imprison them, meeting his own ghastly end at the Battle of Bosworth Field at the hands of Henry Tudor, a descendant of Edward III.

Henry married Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth — thus ensuring his claim to the throne and that the Plantagenet blood, if not the dynasty, would endure.