Without a doubt, American silver in the Japanese taste is one of the most inventive styles in American silver, and certainly one of the most collectible today. For a 20-year period from about 1870 to ’90, American silver won worldwide acclaim. It was a period of great creativity, when form and ornament were integrated and whimsy, humor and even color were incorporated into silver. Much of the credit for the fashion belongs to Tiffany & Co. and its chief designer, Edward C. Moore (1827-1891), who was at the forefront of this movement.

The effect of Japanese art on Western fine and decorative arts in the 19th century is well known, spurred on by the opening of Japan to the West in 1853, after centuries of that country’s isolation. Westerners now had access to a much richer array of Japanese material through trade and travel and though international exhibitions, in which Japan became an active participant.

Dealers, art critics and designers were another important influence in promoting Japanese art. Christopher Dresser, one of the first industrial designers, was one of the biggest promoters of the “cult of Japan.” In 1876, Dresser traveled to Japan and was hired by Tiffany & Co. to bring back Japanese goods for the firm. In total, Tiffany & Co. acquired some 8,000 objects. Half of these pieces were sold at auction and the other half presumably remained in the Tiffany & Co. collection, either for sale or to serve for study and inspiration.

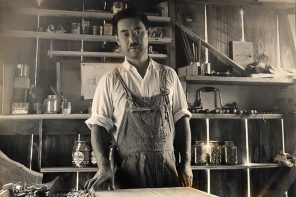

As Tiffany & Co.’s chief designer, Moore had his own varied and extensive collections, including more than 900 pieces of Japanese ironwork, baskets, ceramics, lacquer work and ivory. Interestingly, almost none of these items were silver. It is clear from looking at Moore’s collection (now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan), that these works were rarely copied outright but served as inspiration — a shape, a color, a motif — for a design in silver.

These different influences began to gel for Moore around 1867, when his sketchbook featured silver designs in the Japanese manner. Indeed, Moore had visited the 1867 Paris exhibition and was greatly inspired by the Japanese display there and, possibly, by Christofle’s French works in the Japanese style.

Tiffany’s early silver works in the Japanese style were rather conventional, typically featuring engraved decoration — such as fish, fans, baskets and kimono-clad figures — taken from print sources like Hokusai or birds on flowering branches, inspired by other woodblock prints.

Moore’s Japanese pattern flatware typifies these early works, decorated with different birds inspired by Chinese paintings. Pieces were often further embellished with engraved decoration. Introduced in 1871, the Japanese pattern was the first American flatware pattern in the Asian style. The pattern was later renamed and is known today as the Audubon pattern.

By 1878, however, Moore’s silver in the Japanese taste was radically transformed and was eagerly snapped up by European, American and Japanese collectors and museums. At the Paris Exhibition in 1878, Tiffany & Co. won the Grand Prix for silver and Charles Tiffany was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor.

Moore’s mature style in the Japanese taste concentrates on flora and fauna and is largely devoid of human figures. The decoration is often cast and applied to give it a three-dimensional quality, decoration is placed asymmetrically and, in the finest works, tells a story, much as a painting could. The silver forms have an equally organic quality to them.

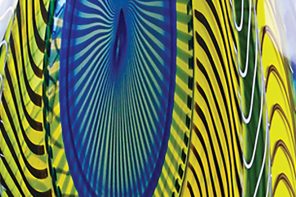

Many of Tiffany’s pieces also featured color, known as “mixed metal.” Gold, copper and alloys stood in contrast to the silver background, which was itself adorned with a hammered and matte surface. Copper was used extensively and often patinated to a raspberry red color, which is reminiscent of Japanese lacquer work. Tiffany & Co. also mastered Japanese metalworking techniques, such as mokume, in which several layers of different precious metals — gold, silver, copper — were layered, folded and flattened to create a wood-grain effect. This charming alloy was used sparingly and for decorative effect, such as on the wings of a butterfly.

A Tiffany & Co. centerpiece circa 1880 is a beautiful example of this mature style. The basket, itself of a highly original shape, has been hammered to imitate a swirling pool of water in which maple keys and mottled and decaying leaves of copper and gold float by as a beetle skirts along the water and a spotted salamander lounges on the shore nearby.

Is it any wonder that imaginative pieces like these continue to enchant collectors nearly 150 years later?

Jennifer Pitman, a Westchester resident, writes about the jewelry, fine and decorative arts she encounters as Rago Arts and Auction’s senior account manager for Westchester and Connecticut. For more, contact her at jenny@ragoarts.com or 917-745-2730.