Traditional Chinese shadow play, a popular folk art for 2,000 years, met its virtual demise when the Communists came to power in the 1950s and Chairman Mao Zedong denounced the freedom-loving puppets as “bourgeois.”

Then during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), Mao’s wife, Jiang Jing, banned shadow puppets in favor of her seven boring, propagandistic “revolutionary operas.” However, after the fall of the scurrilous “Gang of Four” and Jiang’s suicide in 1976, the treasured silhouette puppets ascended again like red phoenixes, to the delight of generations both in China and the West.

Shadow puppets began to emerge from the dark shadows in the early 1980s when the folk art spontaneously reappeared at traditional rural marriages, funerals, banquets and special occasions. Besides entertainment, the story plots of this performing art extol the loyalty, strength and honor of legendary generals during historical battles — generals who are now trending.

According to Chinese historical records, shadow puppets were originally created by a Taoist monk during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) — contemplating how to console the brokenhearted Emperor Wudi, who was grieving over the death of one of his favorite concubines. The Taoist experienced an epiphany while watching children playing under parasols in the noonday sun and became inspired by the lifelike power of the moving shadows. He fashioned a stone image of the emperor’s departed concubine and placed it in a tent illuminated by burning candles, which cast a flickering shadow of the emperor’s lost love. Emperor Wudi saw the resemblance and sensed her spirit. He was comforted. Sadness passed and shadow play was born.

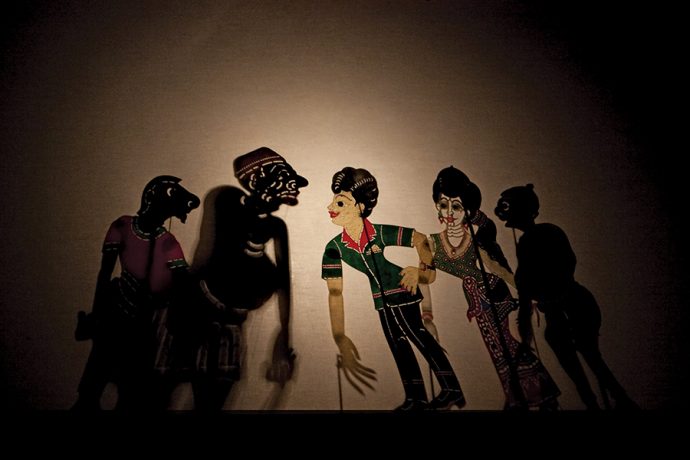

Over the next 2,000 years, the stone figures were gradually replaced by cow and goat-hide leather silhouette images with movable limbs adorned with brilliant, almost psychedelic costumes. Puppeteers with dexterous hands maneuvered the charismatic puppets from attached strings, enabling them to stroke their beards, nod their heads, kick their legs, wave their arms and carry swords. Skills and complex techniques developed. Voices were added so they could curse their enemies and sing their stories in falsetto like old Chinese Opera performers. Music, accompanied by drums and gongs, was added and the puppets became backlit works of art.

Shadow Play is now popular throughout Southeast Asia as well as in China, where a group of passionate artists have protected the tradition against all odds. One of the main leaders is master puppeteer Wang Bao from Langzhong in Sichuan province, who comes from a family that has been performing shadow puppetry for seven generations. With the support of a national fund, Wang is bringing attention back to the ancient art. He broke the tradition of teaching only male students by including females and is now training 22 chosen students in the techniques needed to master the art of puppetry. Wang was taught the art by his grandfather, a renowned shadow puppet performer. He told China’s Xinhua News that it takes years before puppeteers are ready to go onstage.

“Every movement has to be on point.” Wang said. “You need to memorize the whole script and sing the lines of many different characters while showing their emotions with the puppet strings.”

The complex yet sophisticated designs that have evolved in shadow puppetry carry with them China’s human history. The whole enactment in shadow play, including the vibrant costumes, has symbolic or allegorical meaning. Every puppet is an amalgamation of Chinese philosophies, imagery and love of harmony. In June 2011 China adopted a law protecting intangible cultural heritage. Shadow Puppetry was added to the UNESCO list of “Intangible Cultural Heritage.”

Intangible, yes, and priceless.