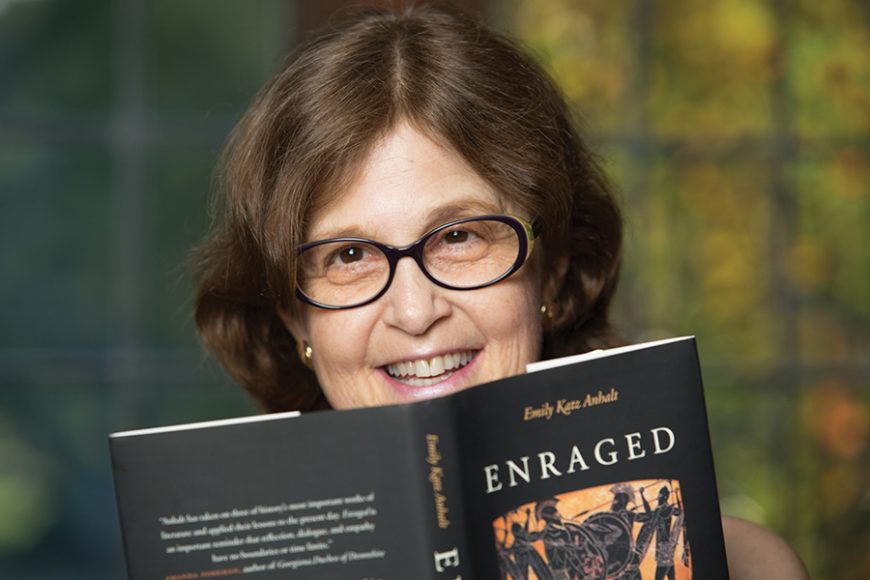

Emily Katz Anhalt, who teaches classical languages and literature at Sarah Lawrence College in Yonkers, has written a timely new book. Not that that was necessarily her intention.

“Sadly, yes,” is how she responds when you note how “Enraged: Why Violent Times Need Ancient Greek Myths” (Yale University Press, $30, 268 pages) resonates. “But it’s been in the works a long time. I was hoping to have it come out before the

(presidential) election.”

Because it came out in September, it must be judged as a work of timeliness instead of one of prescience, though it is both. Anhalt can write passionately, eloquently of the ancient Mycenaean king Agamemnon — one of literature’s great bad leaders — who “epitomizes the most dangerous sort of demagogue, one who panders to the people he ought to lead. Like most 21st century political leaders, Agamemnon cares most about appearances and about his own susceptibility to blame. (The Trojan queen) Hecuba has his number: ‘Since you are afraid,’ she tells him (in Euripides’ play ‘Hecuba’), ‘you distribute more to the ochlos, mob.’ Instead of leading, Agamemnon subordinates himself to the mob. And we have already seen the mob twist wrong into right.”

Yet lest any reader of a certain political persuasion think that she is out to thump Trump and his base, think again. Anhalt is too much of a discerning smart cookie for that and, judging from our conversation with her at Sarah Lawrence, too much of a moderate concerned that “the rational power in the middle is getting obliterated.” She is as worried about violence on the extreme left as on the extreme right, along with the role that all forms of media — not just social media — play in instigating it.

“I worry that a lot of commercial films celebrate violence, equating it with justice,” she says. “That’s going back to tribalism.”

The ancient Greeks and their myths and literature have a lot to say about tribalism; nationalism, which she sums up with the slogan “my country, right or wrong”; patriotism, “the critical assessment of what makes a country stronger”; and just about every other “ism” you can think of. But it’s been a long time since modern society thought the Greeks were relevant.

“It’s an interesting phenomenon,” she says. “To be educated 150 years ago, you read Greek and Latin….” Today, she adds, not many are aware of the ancient Greeks and Romans. But Anhalt, a Guilford, Connecticut, resident, bucked the trend — switching her focus from philosophy to the ancient Greeks at Dartmouth College; earning a Ph.D. in classical philology at Yale University; and teaching Greek mythology, classical languages and history at Yale and Trinity College. Those experiences taught her that the ancient Greeks were a lot more than a bunch of dead white guys who had kept slaves and relegated women to second-class status.

“The ancient Greeks didn’t live up to their ideals initially,” Anhalt acknowledges. “Their transition away from tribalism took centuries….But one of the premises of the book is that the stories we tell shape our attitudes and priorities. You can make all the institutional changes in the world, but unless you address the propensity for violence, it won’t matter. For me, the Greeks are central to what qualities we need to value.”

Among those qualities is an understanding of the destructive power of anger and violence. Anhalt is not talking about righteous anger, the kind that might fuel a constructive fight against social injustice, or the violence in an act of self-defense, as in the Allies’ response to the Axis powers in World War II, but overweening anger and violence — the subjects of Homer’s “The Iliad,” which lie at the heart of her book. (She also addresses two related works — “Hecuba” and Sophocles’ “Ajax.”)

“Rage” is the first word in “The Iliad,” an epic poem that may be as much as 3,000 years old, Anhalt writes. Rage drives its narrative and its protagonist — Achilles, the Greeks’ greatest warrior and one of literature’s most fascinating creations. When we meet him and his fellow Greeks, they have been on the beach for 10 years trying to lay siege to Troy in revenge for the Trojan prince Paris taking off with the beauteous Helen — wife of King Menelaus of Sparta, brother of the Greek high commander Agamemnon.

Now the Greeks are suffering from a plague brought on by the god Apollo to avenge Agamemnon taking Chryseis — daughter of the god’s local priest — as a war prize. When Achilles, a king in his own right, demands Agamemnon respect Apollo and his earthly servant and so return the young woman and assuage the Greeks’ suffering, the high commander seizes Briseis, Achilles’ war prize, to be strong on him.

“It’s tempting to sympathize with Achilles,” Anhalt says. “We have a tradition in America of the rebel hero.” (It helps that the Greeks and later artists portrayed him as one of the great male beauties. In the 2004 movie “Troy,” he was played by Brad Pitt.)

Yet not so fast on the sympathy. Rather than man up, Achilles takes to sulking in his tent (although this being an ancient Greek myth, he does so beautifully, strumming his lyre and singing of heroic deeds). This leads his best bud Patroclus to don Achilles’ armor to get the Greeks back in fighting mode, which leads the Trojan prince Hector, the city’s champion, to kill Patroclus, thinking he’s Achilles; which leads Achilles to go berserk — slaying Trojans left and right and killing Hector, then dragging his body around the battlements in front of the horrified royal family before returning to the Greek camp with it.

“When he succumbs to rage, he goes to the dark side,” Anhalt says.

“For me,” she continues, “Homer introduces distancing between what the characters see and what the audience sees. The characters see honor and winning as primary. The audience sees the characters as honor-obsessed.”

But Achilles transcends this at the end when, visited by the Trojan king Priam, who begs him to release the body of his son Hector for burial, he acquiesces — seeing his own father in Priam and, perhaps more important, Priam’s suffering in his own.

Writes Anhalt: “…Achilles regains his humanity by recognizing human vulnerability to suffering and death and by discovering the value of empathy.”

Emily Katz Anhalt is writing a sequel to “Enraged” based on Homer’s “The Odyssey.” For more, visit emilykatzanhalt.com.