Megalomaniacal world leaders run amok. Celebrities making sex tapes. The hoi polloi capturing every waking moment in selfies and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Sometimes, it seems as if we’re all singers warming up — me, me, me, me, me, me, me.

Indeed, in the spirit of the forthcoming season, I thought you’d enjoy the lyrics from a 2012 Target Black Friday commercial satirizing this effect, sung to “Deck the Halls”:

“One for you and one for me. You, you, you, you and one for me.

Check out the price of this new flat screen. I’ll buy it for Bill, but it’s also for me.

Xbox for Jack. Sweaters for Nancy. I’m blown away. I’m freaking out. Deals, deals, deals.

One for you and one for guess who. It’s on. It’s on. It’s on. It’s Black Friday.

I’m so super-pumped for Target Black Friday.”

Sound familiar? We live in an age of narcissism — or, at the very least, “targeted” selfishness.

So what then does it mean to have a sense of self at such a moment in history? Oddly enough — or perhaps not so oddly — it’s a question that artists of every ilk have wrestled with at other times, not only in their works but in their own careers. The term narcissism, which psychoanalyst Otto Rank first linked to self-admiration in 1911, comes from art, from narrative — the Greek myth about Narcissus, a proud, disdainful youth cursed by the gods to fall in love with his own beautiful, unattainable reflection. Today, the word is used to describe a particularly nettlesome personality disorder characterized by an excessive insecurity and need for attention and a lack of empathy and boundaries.

Ironically, such self-absorption brings with it no self-awareness, because presumably, if you were self-aware you would realize you’re acting like a jerk and modify your behavior accordingly.

The beauty of the arts, however, is that they let us have our cake and eat it, too. We can indulge, explore and exorcise our failings within the safe confines of great works organized in time and space. Some of the most memorable characters — Homer’s Achilles; (see related story); William Shakespeare’s Iago, Edmund and Coriolanus; John Milton’s Lucifer; Emily Brontë’s Cathy and Heathcliff; Herman Melville’s Ahab; and Margaret Mitchell’s Scarlett O’Hara, to name but a few — are creatures of monstrous ego who leave a path of destruction in their wake. Still, literature would be poorer without them. We just wouldn’t want to live next door to them.

You might argue that in some instances self-centeredness is healthy, necessary even, particularly when it benefits the common good. Certainly, Scarlett’s selfishness saves her ancestral home, Tara, and her family as well from the ravages of the Civil War in the American South. But you’d be hard-pressed to convince her put-upon sisters and long-suffering beaus of that — to say nothing of the slaves underpinning her antebellum ideal and many a reader.

It’s tricky, isn’t it? Being self-possessed without being self-absorbed, knowing what belongs to you in this world, what belongs to others and what — and whom — you belong to. For the artist — working one or two jobs to support his passion, then spending long hours, often alone, to realize that passion — this is a particular challenge. For women — traditionally saddled with being the more giving sex — it’s a double bind, one that Hollywood loves. Remember Anne Bancroft’s single-minded ballerina in “The Turning Point.” Having manipulated rival Shirley MacLaine years earlier, she must face being upstaged and replaced by MacLaine’s daughter (Leslie Browne), with only a glamorous apartment and the requisite petite pooch for company. Ah, the price of art.

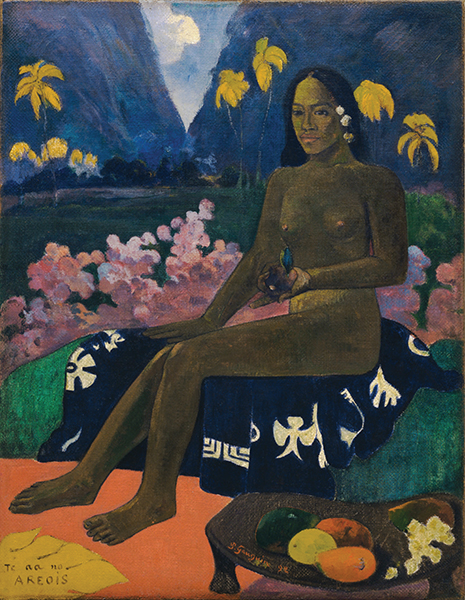

Sometimes, though, it’s the family of the artist that pays the price. In “The Moon and Sixpence,” W. Somerset Maugham fictionalizes the life of Postimpressionist Paul Gauguin in his narrative of an artist who uses and discards others in pursuit of painting. Gauguin contributed to the myth of the self-absorbed artiste, with himself as a prime example. But it’s certainly true that he abandoned his wife, children and the bourgeois life of a Parisian banker for la vie bohème in Tahiti and he wasn’t kind to the admittedly difficult Vincent van Gogh.

Yet he created great art. Was it worth the tradeoff? Maybe to us, yes, but what about

the family?

It’s a tough balancing act — one that many artists navigate by being among the first to donate money, time and talent when charity and crises call. Consider the recent “Hand in Hand” Hurricane Relief telethon, in which performing artists raised more than $55 million.

They seem to understand that we are put on this earth to give joy to others and ourselves. And yet, if you are going to have any kind of creative life, there must be moments when those two are mutually exclusive. You have to go within to reach out, say “no” instead of “yes.”

As long as there are those moments, in the end, when you do say “yes.”