Can you name a renowned woman artist primarily associated with Taos, New Mexico?

Well, yes, there’s Georgia O’Keeffe. But there is also Agnes Martin.

The Canadian-born painter (1912-2004) had a life and career that were full of fascinating contradictions. She began painting traditional narrative themes, but made her name with art that has most often been classified as Minimalist. (She thought of herself as an Abstract Expressionist.) She lived off the grid in Taos, New Mexico — what was then a remote, unfashionable outpost — but became influential in the art world and a wealthy woman late in life. She was intensely private, even reclusive, yet she was active in the Taos art scene and gave generously (and secretly) to several local causes, especially those that benefited disadvantaged youth and victims of violence.

Perhaps most telling, however, was that Martin created a serene body of work that reflected a Zen philosophy despite — or maybe because of — the difficult circumstances she contended with in her long life. She was a lesbian at a time when homosexual acts were considered immoral and even criminal. She was schizophrenic and underwent electroshock treatments. Until her paintings received attention and acceptance late in her life, she experienced rejection and poverty.

Yet she produced a distinctive body of work that radiates spirituality. The facts of her life might indicate a preoccupation with suffering, anxiety and isolation, but that is far from the truth apparent in her paintings and prints. She often gave them such joyful titles as “Happy Holiday,” “Faraway Love,” “I Love the Whole World” and “Gratitude.”

Earlier in her career, Martin had experimented with self-portraits, watercolor landscapes, and biomorphic forms. She soon developed the geometric abstract style that became her signature and later destroyed as much of her early work as she could acquire.

After participating in the vibrant mid-century New York art scene for 10 years, Martin saw her home and studio in lower Manhattan slated for demolition in 1967. She felt compelled to return to Taos, where she had lived and taught in the 1950s after graduating from Teachers College, Columbia University. Building her own small adobe dwellings, she abandoned painting for several years to write and meditate in isolation.

By the late 1950s Martin settled on the restrained, highly disciplined themes, format and color palette that she refined for the rest of her long career.

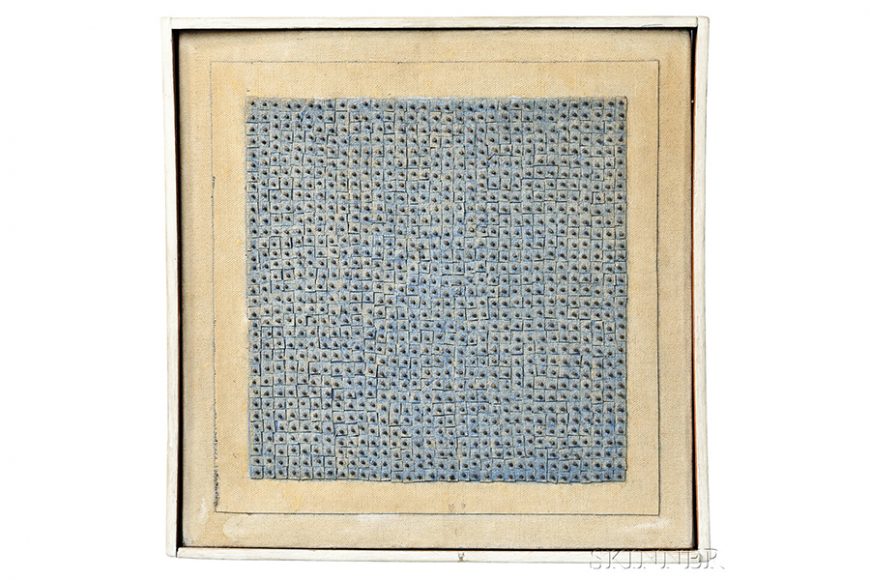

The grid, later somewhat modified into related linear patterns such as stripes and bands, became the defining characteristic of her distinctive work. Martin’s geometries are not exercises in mechanical perfection, however. Close observation reveals tiny irregularities and relaxations, clear evidence of the artist’s hand.

Her paintings were also recognizable by their unusual format — squares measuring 6 feet each side. (When she could no longer manage such large canvases she downsized a little — to 5 feet.) Her works on paper, although much smaller in scale, were also square.

Equally characteristic was her restricted, subtle palette, often applied in light washes of pastel shades. Martin also used multiple media to create a mysterious shifting play of light and form, incorporating graphite pencil, gesso, small nails and gold leaf into her work.

Today her work is gaining even wider recognition, as the market for Modern and contemporary art is ever eclipsing works from before World War II. A Martin retrospective in 2015 at London’s Tate Modern helped to introduce her to a new generation of art lovers, and a catalogue raisonné is underway.

What those art lovers are discovering is that her spare, restrained style served a vision of beauty, mystery and an optimistic response to life. Her grids do not exclude or confine. In her own words, “When I cover the square surfaces with rectangles, it lightens the weight of the square, destroys its power.”

Martin once said in an interview, “I paint with my back to the world.” That thought-provoking comment, both playful and profound, is intimately connected to the Zen philosophy that was Martin’s lifelong interest. It also reveals a final contradiction. Despite her acclaim, Martin did not create her art in order to gain public approval.

And her work isn’t concerned with accurately representing what the eye sees. Instead, Martin’s works are visual meditations on what is felt and known. Her subtle depictions of a state of quiet introspection invite the viewer into a silence that is not emptiness but full of possibilities.

For more, contact Katie at kwhittle@skinnerinc.com or call 212-787-1114.