Director James Ivory is a fan of disaster films. His favorite? “San Francisco” (1936), in which Jeannette MacDonald brings down the house — quite literally as the movie ends with the great 1906 earthquake — singing the title song.

This may come as something of a surprise for fans of his own movies — or rather Merchant Ivory films as they were known in part for the last name of his producing and life partner, Ismail Merchant. Their collaboration with screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala on a number of tony adaptations — mainly of E.M. Forster and Henry James — conjured images of PBS’ “Masterpiece” series. The catastrophes that occurred in their films tended to be psychological rather than physical; the seismic shifts, of the cultural kind as their characters — mainly cosseted, sometimes closeted types — found themselves unmoored from the customs of their countries and their own hearts.

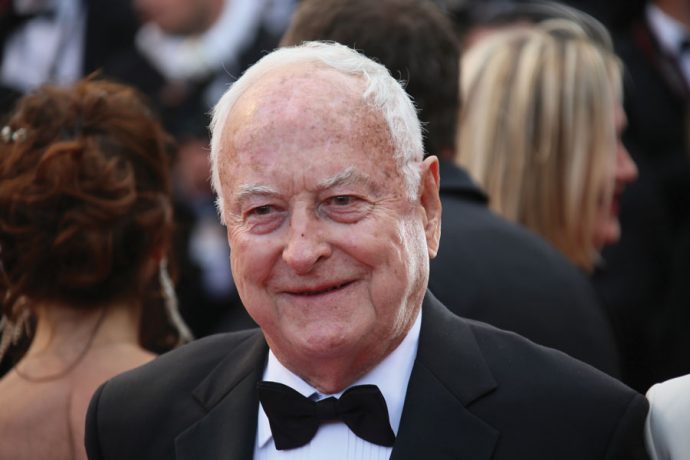

Fans could be forgiven, then, for thinking that the trio — whose 40 films have received 31 Oscar nominations — was “teddibly” “British. But as Merchant, who died in 2005, once noted, “I am an Indian Muslim; Ruth is a German Jew; and Jim is a Protestant American. Someone once described us as a three-headed god. Maybe they should have called us a three-headed monster.”

Not only weren’t they British; they didn’t start out as feature filmmakers either, Ivory said this past summer during a talk at the Greenwich International Film Festival. When it came time for a hesitant Jhabvala to adapt her novel “The Householder” to the big screen in 1963, Ivory recalled, Merchant reassured her by saying, ‘Never mind. Jim never directed a feature, and I’ve never produced one.”

Indeed, Ivory, who was born in Berkeley, California, and raised in Klamath Falls, Oregon, — where there were a lot of movie theaters “going full blast” and where “San Francisco” no doubt left an indelible impression on him as a child — studied architecture at the University of Oregon with the idea of being a set designer. At the University of Southern California, his interests shifted to documentary filmmaking, which in turn led to his meeting Merchant.

Theirs was a prolific partnership — the longest in independent film history — that was conducted with the utmost discretion privately, because of Merchant’s conservative Muslim background. Yet you can’t help but think that the relationship was in a sense up there on the screen in depictions of both gay and straight characters who could not or would not express their feelings for others, often until it was too late (“A Room With a View,” “Maurice,” “The Remains of the Day”).

Still, Merchant Ivory never shied away from passion’s full expression either. This isn’t Hollywood’s call, he told WAG after the Greenwich talk, but the director’s. His “Maurice,” based on Forster’s posthumously published novel, is a tale not only of gay love repressed but of gay love fulfilled.

“What is seen is seen,” he told the Greenwich audience. “What is not seen is not seen.”

In “Maurice,” he explained to The Guardian earlier this year, “the two guys have had sex and they get up and you certainly see everything there is to be seen. To me, that’s a more natural way of doing things than to hide them, or to do what Luca did, which is to pan the camera out of the window toward some trees. Well …”

He was referring to Luca Guadagnino, for whom he wrote the screenplay for “Call Me By Your Name.” Ivory’s screenplay — based on André Aciman’s coming-of-age novel about a teenage boy’s romance with a male grad student — called for nudity, which was nixed by the no-nudity clause in the actors’ contracts. There was something of a he said-he said disparity between Ivory and Guadagnino over whether the director had ever considered a nude scene between stars Armie Hammer and Timothée Chalamet. There’s no disputing the film’s success, however, which earlier this year made Chalamet, as the teen lover, a breakout star and Ivory the oldest Oscar winner to date (at 89 for Best Adapted Screenplay).

But then, Ivory’s work always seems to be associated with breakout stars — Daniel Day-Lewis and Helena Bonham Carter in “A Room With a View,” Hugh Grant in “Maurice.”

“You can’t tell when they’re young if they’re going to go on to big careers,” Ivory told the Greenwich audience. “You had to take it on trust. But you did have a sense of their personalities. Helena Bonham Carter was very young, 19, beautiful, very smart….Daniel Day-Lewis I cast on the spot.”

Another great stage star had a small part in “View” years before she would go on to her own Oscar-winning career — Judi Dench.

“English actors have terrific technique,” he says. “They’re well-trained, which is not always the case of American actors.”

Nonetheless, he says, “good actors are good actors.” He worked with two of the best — Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward — in “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge” (1990), based on Evan S. Connell’s novel of a 1930s Kansas couple confronting a changing world. Their fellow Westporter, distributor Harvey Weinstein, didn’t think the screenings were enthusiastic enough and wanted changes. To which, Ivory said, Newman replied that if he wanted him to do press for the film, he wouldn’t mess with what Merchant Ivory had created.

It remains a favorite film of Ivory’s, along with “The Remains of the Day,” which he recently saw in a digitally remastered print at the Bedford Playhouse and was bowled over by. He’d like to see his “Jefferson in Paris” and “Slaves of New York” restored as well.

As for himself, Ivory keeps working on a plan to bring “Richard II” to the screen with Tom Hiddleston and Damian Lewis, and a detective story to tease Day-Lewis out of retirement.

He’s also adapting Jhabvala’s short story “The Judge’s Will” for director Alexander Payne (“Downsizing”).

“All you can do,” Ivory said, “is follow your instincts and make films about things that interest you.”