With our January focus on the year 2020, we thought it would be fun to look not only at eyes and vision — 20/20, get it? — but at doubles of all kinds, including the tennis game, twins and doppelgängers, our subject here.

The “doppelgänger” — the word comes from the German for “double” and “walker” — is different from the evil twins so beloved by soap operas, historical fiction (“The Man in the Iron Mask”), horror novels and films (“The Other,” “Dead Ringers”) and Bette Davis tearjerkers (“A Stolen Life”). Nor is the doppelgänger the same as an alter ego, perhaps best realized in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” It’s an 1886 novella that has often been reimagined for the stage and screen, perhaps never more poignantly than in the novel and film “Mary Reilly,” which tells the story of the experimenting doctor who transforms himself into a man of unbridled passions from the viewpoint of his compassionate Irish maid.

As with twin tales, doppelgänger stories turn on resemblances and mistaken identities. And the doppelgänger can appear so close to the subject that he may seem like an alter ego, or other self. But the doppelgänger is a separate individual, a nonbiological lookalike who may be different in personality but not necessarily sinister in character — though in truth sinister is how we like it.

Indeed, the idea of a doppelgänger has been a favorite subject of a variety of cultures going back at least to the ancient Egyptians and Greeks, who saw ghostly doubles as harbingers of bad luck and even death. Dante Gabriel Rossetti captures this in his 1864 painting “How They Met Themselves,” an exemplar of the sensuousness and medievalism of his Pre-Raphaelite Movement. In this lush watercolor, a man and a woman encounter their unearthly doppelgängers, ringed in yellow, during a twilight walk in a forest. Swooning in recognition of impending doom, the woman is braced by her male companion, who confronts the ghostly couple with a look of real vehemence.

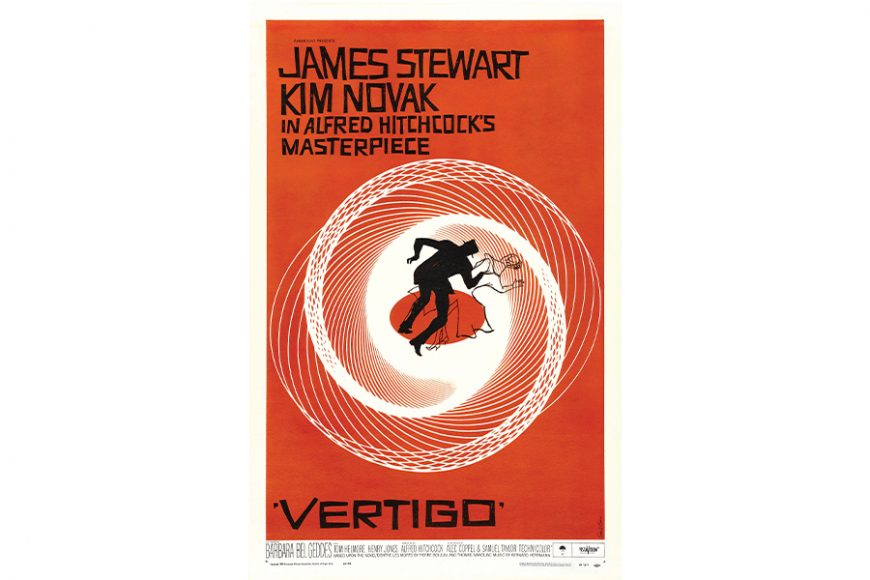

The doppelgänger as malevolent figure has propelled literary works ranging from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “The Double” to Stephen King’s “The Outsider.” It’s at the heart of a movie that a 2012 poll of critics by the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound magazine called the greatest ever, Alfred Hitchcock’s haunting “Vertigo” (1958). The film tells the story of a San Francisco detective, John “Scottie” Ferguson (James Stewart), who falls for the suicidal Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak), whom he’s been hired to protect. We’re giving

nothing away — since Hitchcock deliberately gives away the plot twist mid-movie — to reveal that the woman is imposter Judy Barton (also played by Novak), hired by Madeleine’s murderous husband, Gavin, to make her death look like a suicide. And then things get really interesting. Suffice it to say that Scottie is much like the great Gatsby — see our opening essay — a man in thrall to his love of an illusion.

Such delusion is not limited to art. Capgras syndrome — named for the French psychiatrist who identified it, Joseph Capgras — is a rare neurological disorder in which the sufferer thinks someone close to him or her is an imposter. It’s particularly tragic as the subject — usually a schizophrenic but oftentimes someone with a degenerative condition like dementia — can be fine one moment then turn violently on the “double” who has supposedly taken the beloved’s place. There is little in the way of research, and treatment and results vary with the underlying condition.

But sometimes in art and in life, the stranger wears a friendly face. In Mark Twain’s “The Prince and the Pauper,” Henry VIII’s son, Edward, changes places with an abused lookalike pauper and learns how to rule with compassion, rewarding his new friend with a position of importance at court.

The doppelgänger has also become a darling of the digital age, with the site twinstrangers.net using facial recognition technology to match visitors with their doubles. There have been more than 5.6 million matchups and the results for those who download their passport-style photographs for a fee can be uncanny and moving, as the meeting of Sara from Sweden and Shannon from Ireland attests. In one of the site’s meet-ups, the two bond over a fairy tale Christmas in Dublin.

“Are you twins?” a food vendor asks. “No, we’re not related,” Shannon says to the vendor’s astonishment.

Perhaps not biologically but emotionally?

“Shannon is the best present I could ever ask for,” Sara says of their fast friendship.