It’s fair to assume that Daniel Ksepka wins the “So, what do you do for a living?” game at cocktail parties.

He’s a paleontologist, and not just any kind of paleontologist, but a penguin paleontologist.

He’s one of the foremost penguin paleontologists in the world.

“Well,” he says sheepishly, “we’re a small group anyway. But I’m among the most enthusiastic.”

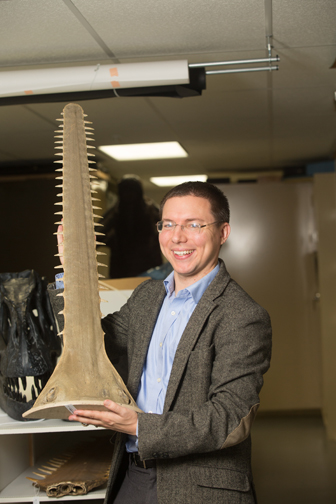

He’s like that — boyish and charming and boyishly charming. Ksepka (pronounced “SEP cuh”) is curator of science at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, where he organized the popular exhibit “Madagascar: Ghosts of the Past” (through Nov. 8). It’s a journey to an island that broke off from Africa and India millions of years ago and is home to lemurs and thousands of other unusual species, alongside prehistoric remains. Like those of the elephant bird — a flightless giant (up to 10 feet tall and 1,000 pounds) that survived until about a millennium ago. Ksepka peers into a case that juxtaposes an egg from an elephant bird (huge) with those of a chicken (tiny) and an ostrich (bigger but still dwarfed by the elephant bird egg). Ksepka says one elephant bird egg could supply 75 omelets (assuming that you, too, like a two-egg omelet).

But Ksepka’s favorite birds are, of course, everyone’s “tuxedoed” faves. Why penguins?

“By definition, every paleontologist is an evolutionary biologist,” he says. “Penguins have been around for 62 million years. The human species is only 6 million years old, so penguins are 10 times older than we are.”

And very different from other birds. Penguins may not be able to fly, but their little flippers and dense bone structure make them ideally suited for their amphibious role in the ecosystem.

“What they do in the water is similar to flight,” says Ksepka, whose “March of the Fossil Penguins” blog has more than 50,000 visitors a year. “I call it ‘underwater flight.’”

Plus, he says, “(they) have such personalities. They fall in love. They steal. They pair off and raise chicks.”

They also transcend traditional roles. Ksepka points to the 1998 story of Roy and Silo, male chinstrap penguins at the Central Park Zoo who formed an attachment and incubated and raised a chick named Tango. There are, he says, a range of behaviors in the animal kingdom.

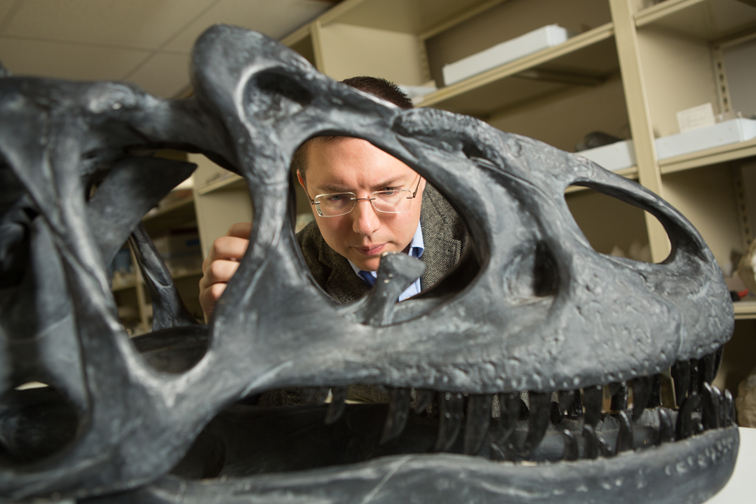

Ksepka has been observing animals since he was a child in New Jersey. That’s when he fell in love with dinosaurs and trains. All kids love both, he says. But dino-might never left this Jersey Boy. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in geology from Rutgers University before going on for a master’s and Ph.D. in earth and environmental studies at Columbia University. Ksepka “practically lived” at the American Museum of Natural History during the five years he spent researching penguin fossil records for his dissertation and learning about curating natural history objects, including skeletal remains, skins and rocks. He did postdoctoral research at the North Carolina Synthesis Center before joining the Bruce in June of last year.

Next up for Ksepka at the museum is “Secrets of Fossil Lake” (Nov. 21-April 17), in which the paleontological sleuth will uncover the remains of days lived 52 million years ago in and around a Great Lake in what is now parts of Colorado, Utah and Wyoming.

When he’s not studying birds, Ksepka is watching them. However, he and wife Kristin Lamm — a Ph.D. candidate in bioinformatics, the science of categorizing complex biological data — share a Stratford home not with birds but with four cats, Oscar, Minou, Giselle and Tabitha, as well as a Mediterranean spur-thighed tortoise named Jane.

What? No birds in the menagerie? Ah, see Oscar, Minou, Giselle and Tabitha.

“We once had a button quail,” Ksepka adds, “but I think birds for the most part prefer not to be pets.”

For more visit brucemuseum.org and fossilpenguins.wordpress.com.