Photographs by Bob Rozycki.

The most frequent visitor to “Ralph Pucci: The Art of the Mannequin” just might be Ralph Pucci himself.

“I go about once a week,” the Greenwich resident says with a smile.

And who can blame him?

The vibrant exhibition at the Museum of Arts and Design in Manhattan — a career retrospective of the man whose work transformed a vital, if often overlooked, element of the fashion industry — has proven so popular it was extended two additional months.

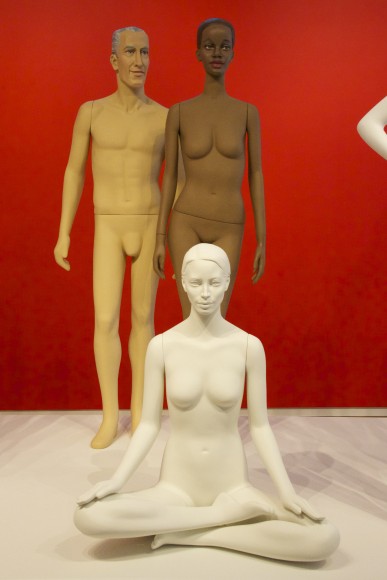

The museum show is eye-catching, to say the least. While it’s attracted the expected fashionistas, its centerpiece — a gathering of dozens of Pucci mannequins set on a runway of sorts — has resonated with a variety of visitors.

“The greatest feeling is (seeing) the people not affiliated with the field getting off the elevator and just smiling,” Pucci says.

In a career filled with groundbreaking, award-winning work, the exhibition continuing through Oct. 25 is proving a special moment for Pucci.

“This is the first museum show we’ve ever had,” he says. “Obviously, we’re very proud of it. To get a New York City museum interested … incredible.”

Pucci is sitting down with WAG on a recent summer morning, having welcomed us to the West 18th Street headquarters of Ralph Pucci International.

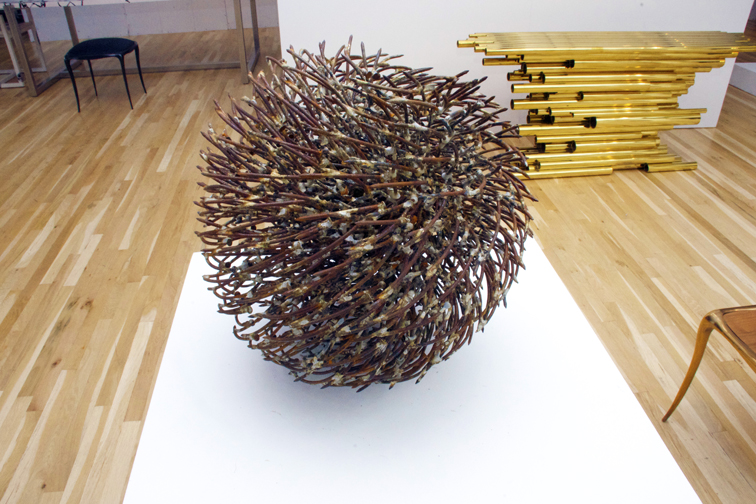

Surrounded by ultra-chic vignettes filled with statement-making furniture, lighting and the most exquisite Murano glass, the space is not only about mannequins, but also the decidedly artistic furniture and interior-design arm of the company. “Everything shown at Pucci is exclusively with me,” he says of the furniture, lighting, floor coverings and art.

This showroom, which anchors others in Miami and West Hollywood, Calif., is where Pucci discusses the mannequins — a creative crossing between the worlds of commerce, fashion and design — now taking center stage.

A CAREER IS BORN

Pucci, who spent nearly two decades in Bedford raising three now-grown children with his wife — one of their sons is part of the business today — also traces his earliest days back to Westchester County, first in Mount Vernon and then primarily in New Rochelle.

Though he often pitched in to help with his parents’ mannequin-repair business, it was not his career plan.

“I studied journalism at Northeastern University, but I’ve always been interested in the arts,” he says. “When you have an open mind, it goes from one creative field to another.”

Soon after graduation, Pucci would join the family firm, making suggestions that were welcomed by his parents. First up was making their own mannequins.

“When you have a repair company, you have all the positions,” he says of the smooth transition. Pucci, though, knew that to succeed they would have to be distinctive.

Then, back in the late 1970s, he says, “The industry was flooded with beautiful, ladylike mannequins. We went in a different way.”

His more sculptural works were welcomed.

“The great thing about the visual industry is they’re very open-armed about new ideas,” he says.

Pucci, always with an eye on what was happening in the world, was affected by the 1976 Summer Olympics and the growing fitness craze and introduced the action mannequin, his earliest success. Its sense of movement and bold hues were revolutionary, catching the attention of major retailers.

Soon, there would be bike-riding mannequins at Marshall Field in Chicago and other effective campaigns.

“When Macy’s San Francisco bought 30 mannequins, 40 mannequins and used them on their ledges. … People are walking off the street to just come in and look at these mannequins.”

Work with national department stores would continue to build the Pucci name, leading to a pivotal moment in 1986.

Pucci was tapped by Barneys New York to work with French interior designer Andrée Putman to create the mannequins for its new downtown store. The job, Pucci says, validated that “we had been doing interesting things.”

And the collaboration, resulting in the bold, Deco-inspired mannequin that became known as The Olympian Goddess, sent ripples throughout the industry.

“It just exuded a whole different feeling,” Pucci says. “That was all Andrée, but we were there to execute it.”

It would spark decades of collaborations with those in fashion, art and design that continue to today. Over the years, the Pucci mannequin has come to reflect trends in art and music, fashion and form, ideals of beauty and more.

There would be a nod to Marilyn Monroe (1988’s The Mistress); fashion artist Ruben Toledo’s Birdland of the same year, a fluid piece originally designed to showcase jewelry; Ada, a 1994 work with children’s illustrator and author Maira Kalman (a collaboration inspired by Pucci’s reading her books to his children); and Nile, the 1995 work with artist/designer/architect Patrick Naggar that’s part mannequin, part ancient vase. Pucci has also worked with fashion and art luminaries from Veruschka to Anna Sui, Kenny Scharf to Christy Turlington and, in 2013, Diane von Furstenberg, to create the mannequins used in celebrating the 40th anniversary of her iconic wrap dress.

The mannequins also have worked in an educational setting, as the basis for “Pratt + Paper & Ralph Pucci,” an exhibition of designs in paper by students at Pratt Institute’s School of Art and Design presented a few years ago.

In addition, Pucci’s early work with Putman fueled his diversification, sparking further collaborations with her in design and helping launch his furniture division that has included work with such legendary figures as Vicente Wolfe, Vladimir Kagan and Jens Risom.

MAD PERSPECTIVE

The mannequin has been a constant in the Pucci world.

Barbara Paris Gifford, curatorial assistant at the Museum of Arts and Design who organized the show with MAD’s chief curator Lowery Stokes Sims, says the mannequin itself connects with people in a very basic way.

“They’re human proxies, so there’s an inherent fascination with them.”

The retrospective grew, she says, out of the first MAD Biennial in 2014, which spotlighted dozens of “NYC Makers,” including Pucci. His sleek red action mannequins were more than memorable — and eye-opening for the MAD staff itself.

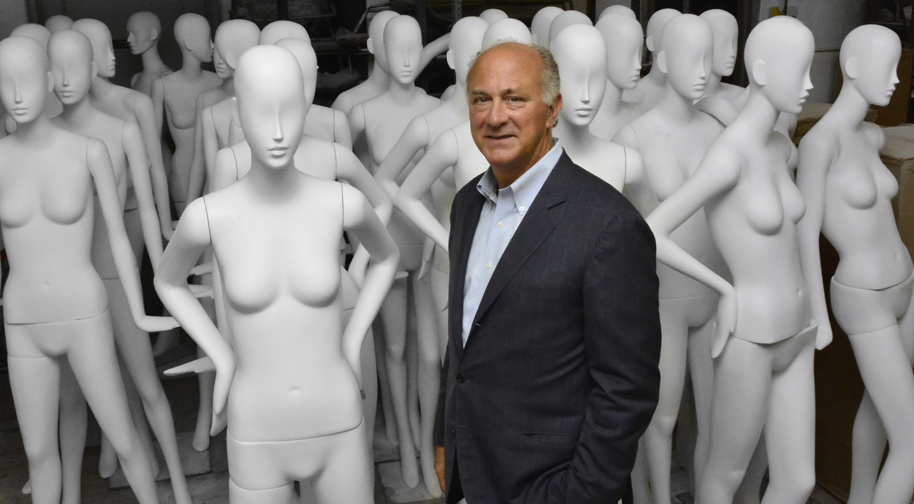

The team ended up going to the Pucci headquarters, says Gifford, who vividly remembers her first impressions.

“There he was, this very elegant man in this sea of naked mannequins,” she says with a laugh. “It was kind of a funny picture.”

But soon enough, she adds, she “discovered this wealth, really, of an artistic kind of information and history that would really be appropriate for this museum.”

The story fit MAD’s mission, she says.

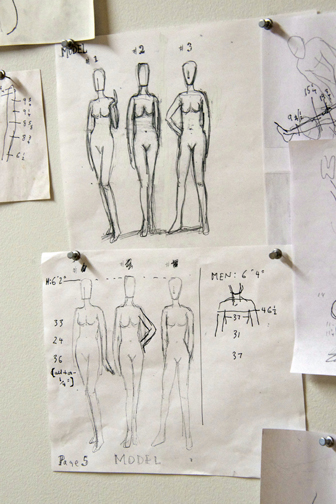

“What we were really interested in, of course, was the sculpting process and the ‘making process,’” she says. “Also, we were interested in the design behind it and all the artistic personalities.”

Throughout, she says, something became clear: “It sort of charts this history of American culture.”

As Pucci shared his history, she saw something more universal.

“We started talking about each individual mannequin and these stories were just so rich, and I realized this is a treasure of our American culture.”

It also serves, she says, as a testament to the mannequin’s most basic role.

“Ultimately, you’re trying to relate to people in retail,” she says. “Ultimately, you’re trying to present fashion.”

STUDIO WORK

As Pucci leads us into the sculpture studio at the Pucci headquarters, there is almost a sense of déjà vu since the MAD exhibition partly recreates this airy space.

Master sculptor and longtime collaborator Michael Evert, who’s on hand this morning, is also in residence throughout the exhibition, giving visitors a weekly look at how a mannequin goes from sketch to clay model through final fiberglass creation, a process all completed in-house at Pucci.

Crowds are known to gather at MAD for the Thursday evenings of Evert’s live sculpting, which have included sittings by the likes of Mary McFadden, Sui, Kagan and Margaret Russell, the Architectural Digest editor-in-chief, a longtime Pucci friend who wrote the foreword to the exhibition publication.

As she writes in that piece, “Part businessman, part impresario, and all creative visionary, Ralph plays a singular leading role in the world of design.”

And, Russell later adds, “Clearly, Ralph is a brilliant businessman, driving hard bargains and monetizing opportunities that his competitors might have dismissed. But his world is as much about promoting creativity as it is about managing his profit margin. No one else mixes commerce, culture and community quite like he does. Where else but at a Ralph Pucci showroom will you see a product launch accompanied by a theatrical modern dance troupe or amid a display of edgy fashions by young designers that Ralph is excited about?”

STRUTTING AHEAD

Pucci’s vision has never wavered, which has made his work remain so important, MAD’s Gifford adds.

“I’m not sure he exactly realized how culturally rich these objects were. These are art objects.”

And they also speak to a specific artistic tradition and integrity.

“It’s important to realize, too, that all mannequins are not made like this anymore,” Gifford says. “This is a very Old World way of doing mannequins.”

Again, she says, it’s due to Pucci’s savvy take on culture and business, branching out into furniture, art and home design.

“Having that diversity has allowed him to not compromise on the other side of this business.”

That, Pucci agrees, holds no interest for him.

“I do not work with the mass retailers that need 5,000 mannequins for two, three hundred dollars,” he says.

Today, he says, there is a need “to find something different. There’s a lot of sameness out there.”

His is a world of constant exploration, from catching some jazz, gallery shows or theater in the city to jaunts to DIA: Beacon, a favorite regional destination.

“I try to see as much as possible,” Pucci says. “Whenever I travel, the first thing I do is go to the museum or galleries.”

As it has for decades, what Pucci experiences himself is translated into innovative mannequins that are launched into the fashion world with the artistic fanfare they deserve.

Pucci wouldn’t have it any other way.

“People come to Pucci to expect the unexpected.”

“Ralph Pucci: The Art of the Mannequin” continues through Oct. 25 at the Museum of Arts and Design, at 2 Columbus Circle in Manhattan. For more, visit madmuseum.org or ralphpucci.net.