In 19th-century France, a perfect storm of revolutionary equality and maritime botanical discoveries ushered in a new era of landscaping and, with it, a new approach to art.

This is the charming theme of one of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s prettiest exhibits. “Public Parks, Private Gardens: Paris to Provence” (through July 29) draws on The Met’s superb collection of Franco paintings, drawings, photographs, prints, illustrated books and decorative objects, showcasing an all-star lineup from A (photographer Eugène Atget) to V (Vincent van Gogh).

Before the French Revolution of 1789, the exhibit notes, French garden design was formal — symmetrical and geometrical — as seen in the work André Le Nôtre, who magnificently landscaped the palaces at Versailles and the Tuilleries for Louis XIV (reigned 1643-1715), and in elegant Adam Perelle etchings of those gardens that emphasize straight-line perfection and a commanding use of perspective.

With revolution, however, came the notion that “the pleasures of the king would be the pleasures of the people.” Out with the regimented jardin à la française and in with the undulating, winding verdure of the English park. Ironically, it took an empress to give the new style a little push. At Malmaison, her estate just northwest of Paris, Josephine Bonaparte, first wife of Napoléon I (reigned 1804-14/15), also kept a glasshouse that became a mecca for the botanical treasures culled from an age of exploration. She is represented here not only by some exquisite watercolors that conjure her as a goddess or depict her now lost hothouse, dismantled in 1826 — oh, to jump into those canvases — but by the rarified drawings of botanical illustrator Pierre Joseph Redouté, who meticulously documented each of her rare specimens, especially her fabulous roses. His work remains an apotheosis of the genre.

It was Napoléon’s nephew and heir — Napoléon III, who reigned from 1852 to ’70 — who would transform Paris into the city of verdant boulevards, pastoral parks and sparkling squares that we know today, particularly from such films as “An American in Paris” (1951) and “Gigi” (1958). It was not long before every red-blooded Frenchman wanted to be a Napoléon — at least from a botanical standpoint — in his own home.

“One of the pronounced characteristics of our Parisian society,” French journalist Eugène Chapus observed in 1860, “is that…everyone in the middle class wants to have his little house with trees, roses and dahlias, his big or little garden, his rural piece of the good life.”

Is it a coincidence that the rise of the burgeoning, meandering garden and park paralleled the ascent of photography — an art form created by the French in 1839 that encourages wandering — and of the plein air (outdoor) painting that would yield Impressionism and Postimpressionism? We think not. The resurrected Parc Monceau, for instance, inspired, among other works, an 1877 Gustave Caillebotte painting of distant figures on a canopied, curving path that suggests all the leafy mystery of a spring/summer day.

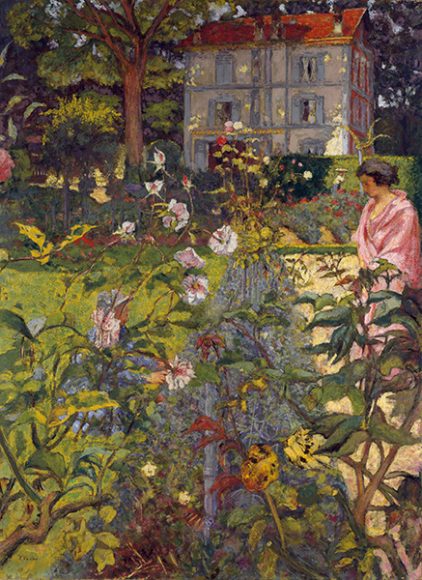

With the more informal, intimate pleasures of the revamped French park or garden came a freedom of composition, a loosening of brushstrokes, a brighter, lighter, riotous palette — in short, a joie de vivre on canvas that has made the Impressionists and Postimpressionists perennial favorites. And this extended to a new approach to the still life and floral painting, which had heretofore been ordered, precise, ladylike. (Earlier on, flower painting had been one of the few accepted arts for women.) Now the floral canvas was free to be a pitcher of thickly bunched Van Gogh irises headed in a variety of directions or curling Van Gogh sunflowers on a flat surface.

Considering these works grouped together offers a fresh perspective, one that finds us grateful to France’s historical landscapers.

Without them, there would be no Paris — and no French art — as we know them.

For more, visit metmuseum.org.