In the world of contemporary art glass — without doubt one of the auction industry’s hottest markets — it is Dale Chihuly’s name that has the greatest star power and commercial success.

Chihuly’s recent blockbuster show at the New York Botanical Garden is a testament to this artist’s popularity. But it is Lino Tagliapietra who is regarded as the field’s ultimate luminary and a living legend — and he’s still designing and creating glass at age 83.

Chihuly has described Tagliapietra as “perhaps the world’s greatest living glassblower.” Tagliapietra’s technical prowess is matched by his talent for design and innovative techniques. Above all, Tagliapietra is revered within the Studio Glass community for his collaborative approach. By sharing his knowledge and techniques with fellow glassmakers, he broke with the tradition of secrecy that had surrounded Italian glassmaking for centuries and propelled forward the American Studio Glass movement.

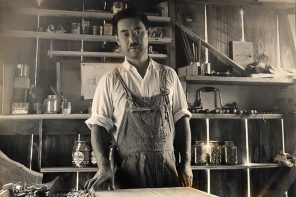

Tagliapietra was born in 1934 on one of the islands surrounding Murano — about a mile north of Venice — and left school around age 10 to learn the glassmaking trade. By his early 20s, he had risen to the most accomplished level of glassblowing — maestro — and then spent his career working for a number of Murano factories. Traditionally, they sharply demarcated the role of glassblower and designer. But Tagliapietra began blurring these lines by developing his own designs, many of which were put into production. While traditionally only the factory name appeared on a work, Tagliapietra began to sign his own name on his work late in his career.

Tagliapietra’s collaboration with other designers and glassblowers, like Marina Angelin and Chihuly, and his association with the newly established Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington, transformed his own work. By the mid-1990s, when Tagliapietra ceased collaborating with others to concentrate on his own work, he became bolder in his technique and his realization of color and form. The results were astonishing.

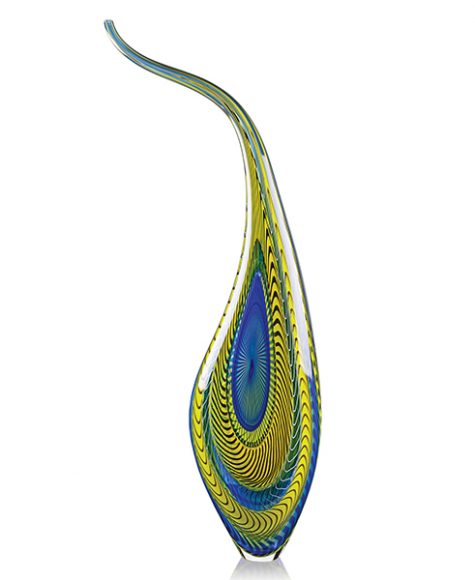

With the help of his assistants, Tagliapietra continues to make glass himself, often making decisions about the piece in front of the furnace. He rarely uses premade colors, instead relying on old recipes. With his decades of experience, he manipulates the glass to incorporate different patterns and colors, from filigree to painter’s brushstrokes. Some pieces are further embellished after the glass has cooled with cold-work, which encompasses engraving and cutting to add texture to the vessels and results in different effects on the glass’s reflection. For example, battuto imitates hammered metal and inciso creates slender grooves.

Today, most major institutions have acquired examples of Tagliapietra’s work for their collections and his glasswork has been the subject of numerous exhibitions and monographs. Locally, Tagliapietra’s work can be seen at the Seven Bridges Foundation in Greenwich, which has an extraordinary collection of modern glass.

Tagliapietra’s pieces are now also well-established in the secondary market — where his works sell at auction at prices that range from $1,000 to more than $40,000. According to Suzanne Perrault, Rago Auctions’ contemporary glass specialist, Tagliapietra’s early works are the most affordable, because as editions they are made in multiples and don’t feature the extraordinarily complex techniques and cold-work found in later pieces. For example, the “Oggetti” series of brightly colored eggs, the “Pueblo” series inspired by Native American pottery and the “Rainbow” series can sell at auction for around $1,000.

Later works, representing Tagliapietra’s most mature period, are highly coveted and often bring prices in the tens of thousands. The colorful “Flying Boats” series, with pieces more than 5 feet in length, is embellished with complex canes and cutting, and the resulting forms have a floating, ethereal quality. The “Dinosaur” series, so named for its oversized shape and elongated neck, beautifully evokes these extinct creatures. The “Batman” series uses multicolored glass canes and cold-working to create a dense opaque vessel evoking a reptile’s scaly skin.

Aside from edition size and the sophisticated nature of later work, what other factors affect the value of Tagliapietra’s work at auction? According to Perrault, signed pieces will garner a slight premium over unsigned works. But above all, the condition of the piece is the key factor. While glass artists are far more forgiving of inclusions in the making, such as a bubble, or other minor damage, collectors are adamant that the work be free of these imperfections and will pay a premium for glasswork that is devoid of any nicks and scratches.

For further reading, see Susanne K. Frantz’s, “Lino Tagliapietra: In Retrospect” (2008). For more, contact Jenny Pitman at jenny@ragoarts.com or 917-745-2730.