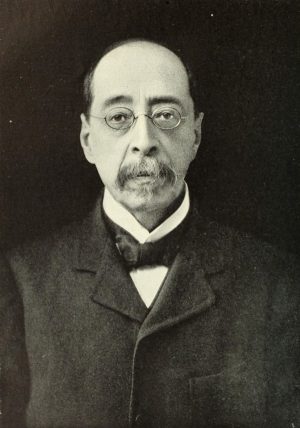

“John La Farge … our sole ‘Old Master,’ our sole type of genius that went out with the Italian Renaissance.” Royal Cortissoz, art historian and art critic for the New York Herald Tribune, wrote those words in 1911. Today’s art lovers are reaffirming this admiration for a multifaceted man whose reputation went into eclipse for much of the 20th century.

La Farge is best known for his achievements in stained glass, a traditional medium that he helped transform and revive in the later 19th century. But La Farge was a man of encyclopedic knowledge and many talents — a highly accomplished painter, art historian and lecturer (among other venues, he lectured at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, where several of his works enrich the permanent collection), interior designer, muralist and author. His circle of friends included such eminent figures as architects H. H. Richardson and Stanford White, painter Winslow Homer, novelist Henry James, his psychologist-brother, William James, and historian Henry Adams.

Born in New York in 1835 into a cultured and successful French émigré family, La Farge was bilingual (as children, he and his brothers produced a handmade magazine they titled Le chinois) and began learning to paint in watercolor when he was in grammar school.

Throughout his life, La Farge remained a serious student with wide-ranging interests. His respect for and knowledge of diverse artistic and cultural traditions was combined with a taste for fearless and fruitful technical experimentation.

In 1856, having completed his law studies, he was rewarded with a trip to Europe. He soon began to study painting seriously and his life took a new direction. When he returned to the United States in 1857, he married, moving to Newport, Rhode Island, and studying with the artist William Morris Hunt.

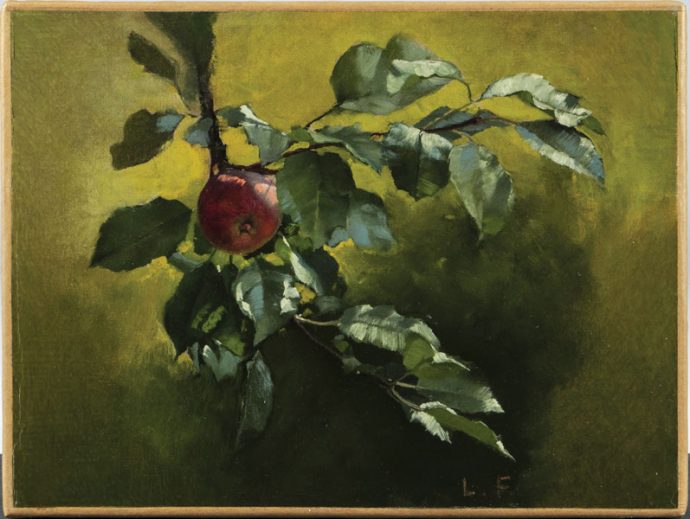

In the 1860s and ’70s, La Farge painted primarily landscapes and still lifes. He also did illustrations and engravings for books and magazines and began his intensive study of Japanese woodblocks. His rise to prominence began in 1876, with his murals and stained-glass designs for H. H. Richardson’s Trinity Church in Boston. This successful collaboration led to many other important schemes for public buildings, including St. Thomas’ Church and the Church of the Ascension in Manhattan, as well as private commissions for prominent patrons such as Cornelius Vanderbilt.

La Farge’s energies were largely directed toward his innovative stained-glass windows. Both in terms of artistic design and technical achievement, his work was remarkable. He is credited with the development of opalescent sheet glass by blending and layering different colors. La Farge was awarded patents for his new methods. Conflicts with his contemporary and rival, Louis Comfort Tiffany, resulted in threatened lawsuits that were eventually dropped.

His fascination with stained glass and the unique effects of color and light that could be achieved in that medium encouraged his work in watercolor, long considered subordinate in importance to oil painting but beginning to be widely popular and greatly respected at the end of the 19th century. La Farge frequently used watercolor to make studies for illustrations and decorative projects, to record his travels and to paint sparkling floral pieces for exhibition and sale.

The brilliance of both watercolor and colored glass depends on translucency, and La Farge found watercolor the ideal medium to develop sketches for stained-glass compositions. The importance of watercolor in his artistic development is shown by the fact he produced at least 1,200 watercolors during his career, almost twice as many as his oil paintings, stained-glass projects and murals combined.

In the 1880s, La Farge began the travels abroad that continued until his death. His trips to Japan in 1886 and to the South Seas in 1890-91, both in the company of Henry Adams, were the source of some of his best-known watercolors. These plein air paintings captured subjects that were then little known and exotic. Japan had been open to the West for fewer than 35 years. South Pacific islands such as Fiji, Tahiti and Samoa had been seen only by adventurous mariners, merchants or scientists.

La Farge’s watercolors are characterized by lively brushwork, jewel-like colors and a respectful curiosity about the cultures being depicted. They, along with his drawings, are probably the most accessible and characteristic of his works, and examples are much sought-after by collectors.

Like many of the great masters with whom he was compared, La Farge’s creative genius belied a lack of business acumen. When he died in 1910, his bank balance was $13. His artistic legacy, however, is priceless.

For more, contact Katie at kwhittle@skinnerinc.com or 212-787-1114.