In the center of the bustling city of Nairobi, Kenya, stands Nairobi National Park and, within the park, a special place, affectionately called the Nursery.

It’s an orphanage that treats baby elephants as if they were human babies — maybe even better — with each cared for by one person, who sleeps with the orphan each night on a simple plywood bed raised 3 feet off the ground and built into the walls of each stall. (In earlier times, I was told, the caregivers slept on the ground with the elephants.)

The caregivers’ titles are either elephant keeper or project manager. Most of them are in their 30s. They are part of The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and its Orphan’s Project, which we touched on in November WAG and which is today the most successful orphan-elephant rescue and rehabilitation program in the world.

Elephants arrive at The Trust — which Daphne Sheldrick created in honor of her late husband, the naturalist and founding warden of Kenya’s Tsavo East National Park — for different reasons. Most often, poachers have killed the mother and family for their ivory. Elephant society is comprised of bonded female units, which stay together for life. A baby cannot survive for the first two years of life without its mother’s milk and, for the next three years, eats a diet of vegetation with some milk from its mother.

When a calf is orphaned, its chances of survival are, therefore, slim. Although the family will do its best to raise and care for it, without sufficient milk from another lactating female, it will become weak and inevitably be left behind, a final decision of the ruling matriarch, whose primary duty is the survival of the herd. In 30 years, the African elephant population has dwindled from three million to under 250,000. Now with help from local people who report animals in distress, a rescue team can arrive promptly, oftentimes with a helicopter, for quick transport to Nairobi.

During a Nursery visit, our anticipation builds until the elephants parade out in single file, each announced by name. One baby, Luggard, had been shot in the leg. His mother was also shot and had to be euthanized due to the severity of her wounds. Luggard survived the ordeal, but he will never walk normally again. However, even with an obvious limp, he keeps up with the others. And with the help of the Orphan’s Project, he’s been doing well. He instantly becomes our favorite.

Luggard is one of more than 150 infant elephants that The Trust has successfully hand-raised. Generally, the babies will remain at the center until they are 3 years old and sometimes longer, depending on their personalities and under what circumstances they first arrived. When they are deemed ready to be independent again and can recall what it was like to live in the wild, they are released into Tsavo — the only park large enough to accommodate sizeable herds in perpetuity.

The Trust is not only saving baby elephants (and baby rhinos and hippos), however. It’s transforming the way Kenyans think about the four-legged creatures in their midst. One of the personal caregivers at the orphanage is a Samburu man. After years spent working with elephants at The Trust, he now understands their value and is eager to tell his fellow tribesmen.

As a tribesman, he was raised to see elephants and other wild animals as threats to livestock and the Samburu way of life. Today, new orders of protection for the elephants combined with drought and human encroachment on elephant land have created complex and controversial conflicts between the conservation of elephant populations and preservation of human life among the Samburu.

The Orphan’s Project can transform you as well (as it did us). For an annual fee of $50, you can select the orphan you want to help and you will be given monthly updates on how your baby is doing. All proceeds go toward improving the orphans’ care.

To foster online or for more information, visit sheldrickwildlifetrust.org.

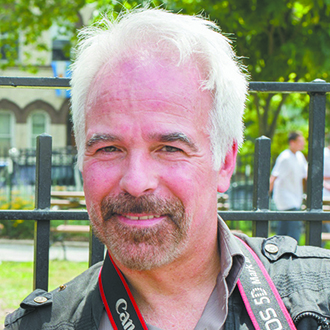

John Rizzo is a WAG staff photographer who offers group tours to Africa to see the mountain gorillas in Rwanda, the tribes of the Omo Valley in Ethiopia, wildlife safaris in Kenya and Tanzania, and the Gerewol Festival in Niger. For more, visit johnrizzophoto.com.