Claude Monet. Frida Kahlo. Dale Chihuly. Roberto Burle Marx. Roberto who?

Over the years, the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx has celebrated a number of famed artists with deep connections to the land. But for its year of #plantlove — in which it is exploring the absolute necessity of botanicals in our lives at a moment when they are under increasing threat — the garden is creating a show about a landscape architect/artist who, while well-known in his own day, is hardly a household name today.

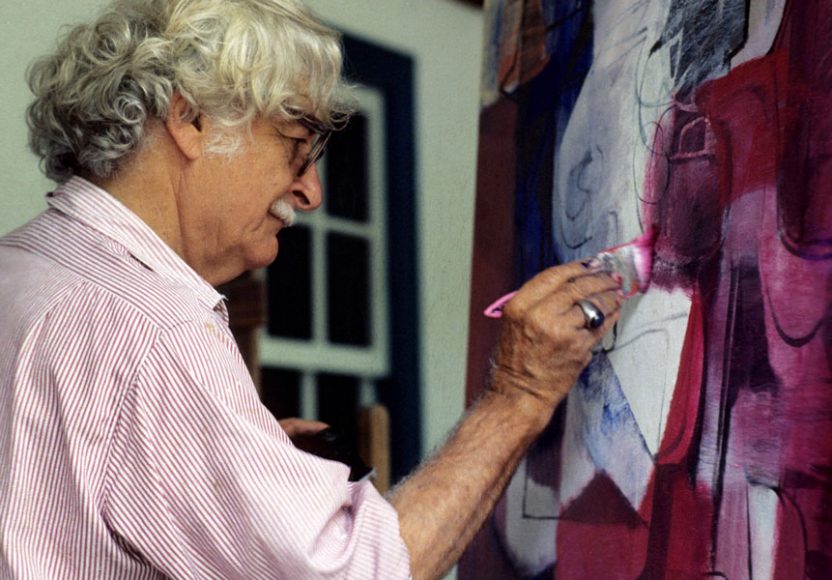

And yet, Roberto Burle Marx (1909-94) put his stamp on the Americas in private and public spaces that melded his protean creativity; his love of key isms — Modernism, Cubism, Abstractionism; his passion for the flora, fauna and folk art of his native Brazil; and his fascination with the sculptural quality of plants, the mosaic potential of pavement and the reflective capability of water.

“Burle Marx embodied plant love in every aspect of his life,” says Joanna Groarke, the garden’s director of public engagements and curator of library exhibitions. “Whether it was the boardwalk on Copacabana Beach or private and public gardens in his native São Paulo, his sculpture, jewelry and tapestries, he was constantly creating. His love of the natural world permeated every aspect of his art, and that’s seen in his love of gardens.”

The botanical garden plumbs that love in its “The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx,” on view June 8 through Sept. 29. For the exhibit, it will not be recreating any one garden by Burle Marx, whose work includes the landscape design for Itamarty Palace, headquarters of the Ministry of External Relations in Brasília, Brazil; the colorfully patterned sidewalks and medians of Biscayne Boulevard in Miami; and the Cascade Garden, offering a touch of South America at Pennsylvania’s Longwood Gardens; as well as the wavy Copacabana promenade.

Rather, the garden has worked with landscape designer Raymond Jungles, a friend and admirer of Burle Marx’s, to transform the green expanse outside the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory. There will be undulating pathways, rich patterns, water features, architectural elements and, of course, plants, including Burle Marx’s beloved brilliant bromeliads.

“(Burle Marx) was an ardent advocate for conservation,” Groarke says. “That’s another part of the story” — one that will be addressed in a June 7 symposium. There will also be music and culinary offerings as well as an exhibit of his increasingly abstract drawings, paintings, prints and tapestries of his last 30 years in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library, curated by Edward Sullivan, deputy director of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts; and a Poetry Walk, featuring the works of the peripatetic Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Elizabeth Bishop, who translated Brazil’s João Cabral de Melo Neto and Carlos Drummond de Andrade, among other Latin American poets.

All of which would’ve been music to the ears of the multitalented Burle Marx, who once studied opera. (His oldest sibling was the pianist, composer conductor Walter Burle Marx, who guested with the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland, Detroit and Washington symphony orchestras.) Situated in Rio de Janeiro, theirs was a musical, linguistic family, headed by their father, Wilhelm Marx, a German-

Jewish entrepreneur; and their mother, the former Rebecca Cecília Burle, a music teacher from an old Brazilian Roman Catholic family of French-

Portuguese-Dutch descent.

Groarke says that a nanny first introduced the young Burle Marx to the native plants of his homeland. But sometimes you have to step away from something close to you to understand what you have. It wasn’t until Burle Marx visited the Berlin-Dahlem Botanical Garden and Botanical Museum, while studying painting and opera in Germany, that the varied beauty of the flora of his country really hit him. Returning to Brazil in 1930, he began collecting plants and attended the National School of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, where he soaked up whatever he could from botanists as well as artists and architects. He did his first landscape, for a private residence, in 1932. Five years later, he garnered international acclaim for his dramatic roof garden for the Ministry of Education building in Brasília.

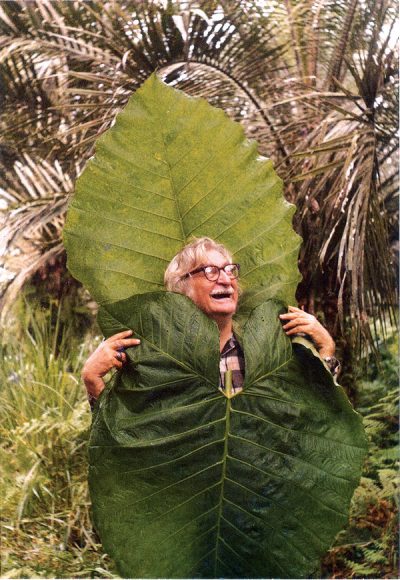

He is, however, one of those artists/landscapers who is as well-known for the way he lived as for the work he did. In 1949, he acquired an estate in Rio that would become the base for his artwork, cultural salons and excursions into the rainforest with scientists, landscape designers and other guests to collect plant specimens — for which, Groarke says, he was a generous host.

Today, the Sítio Roberto Burle Marx, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a 40.7-acre complex that includes Burle Marx’s home and library and a collection of more than 3,000 items set amid his landscaping and gardens.

It, along with his other garden designs worldwide is, Groarke says, the legacy of a man of “creative vision, who thought in a way that surpasses any one discipline.”

For more, visit nybg.org.