Different countries seek empowerment in different ways. The Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan – “Land of the Thunder Dragon” but also an insular world where the horse is still central to farming, travel, art and the soul of Buddhism – holds weeklong empowerment ceremonies, which are as popular as the Super Bowl is in the United States.

While skiing in Colorado in 2002, I was lucky to meet Kunzang Pema Namgyel, the High Lama or Tulku (meaning Living Buddha) of the Gangteng Monastery in Bhutan. He was supervising the construction of a Buddhist monastery in Crestone, Colo., and agreed to an interview.

I learned that the Gangteng (or Gangtey) Monastery was founded five centuries ago. It still sits close to the heavens amid the fabled Himalayan Mountains and is considered one of the holiest Buddhist sites in the world. The main temple houses some of the most sacred artwork in Bhutan, but is in urgent need of renovation. To initiate this, the Tulku planned to hold an empowerment ceremony and a Tshechu, a 10-day celebration of Lama Dances.

Bhutan – a country about the size of Switzerland with a population of some 2 million – is the last jewel in Buddhism’s Himalayan crown. For centuries Buddhism flourished in the verdant valleys of the Himalayas. One by one, all the other Buddhist kingdoms in this mystical cosmos, so close to nirvana, have been swallowed up by bigger powers. Earlier Buddhist civilizations stretching from Afghanistan to Mongolia and Turkestan were overtaken in the 10th century by Islam. Then in the 1950s, Tibet, Bhutan’s mentor, was claimed by the People’s Republic of China. In 1975, India absorbed Ladakh and Sikkim, leaving Bhutan sandwiched precariously between two populous giants, China and India.

Although it is a country without military might, Bhutan has managed to make peace with its powerful neighbors. The lamas and statesmen of Bhutan, like the Dalai Lama of Tibet, have excelled in the study of consciousness and developed a highly involved environmental ethic. This mystical kingdom is advocating cultural values that demand serious consideration by the modern world that go far beyond romantic curiosity.

“What if anything can America learn from Bhutan?” I asked the High Lama.

“Militarily or economically, Bhutan has nothing to offer the United States, but in terms of realizing mental happiness and contentment Bhutan has much to offer,” he said. “Our traditions are about peace, contentment and harmony with each other and our protected environment. With the intense pace of modern existence, our way of life is a powerful example that Americans could utilize and learn from.”

The kingdom of Bhutan, like England, is a constitutional monarchy ruled by a parliamentary democracy. In 1907, the present king’s wise great-great-grandfather, Ugyen Wangchuck, (with the encouragement of the British colonial government in India) united the country and established a hereditary dynasty with himself as “The Dragon King.” Before that, Bhutan was a country of warring valleys with a 300-year-old dual system of secular leaders and Buddhist saints entwined in a history of magic and mystery. After the interview, the High Lama invited me to Bhutan to attend the empowerment ceremony as a guest at the monastery. I accepted with pleasure, but soon discovered, that Bhutan is not an easy place to get to. In fact it is one of the world’s least accessible nations, one that even sophisticated travelers had never heard of, but then the Bhutanese had never heard of us, either. For centuries they remained isolated on their own “Roof of the World.” The country was not involved in the Industrial Age, the world wars, the sexual revolution, the arms race or even, until recently, cyberspace.

In 1997, the fourth king of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, initiated a program called “Gross National Happiness.” He declared that Bhutan’s main concerns are the preservation and promotion of its traditional culture, the care of the environment, good governance and economic development.

Looking forward to my empowerment in the Land of The Thunder Dragon, I flew to Bangkok where I met Kate Steichen, a friend and fellow photographer from Colorado. We boarded a small Druk airplane and headed north over the Himalayas toward Paro Valley. Circling over the only airport in Bhutan, we were terrified to see a narrow landing strip, squeezed hazardously between the rugged mountains peaks, but the stewardess told us not to worry because the plane had been blessed by lamas. I already felt empowered. We continued by bus to the capital city of Thimphu, a city in the process of modernization and the only city on earth where “dancing policemen” take the place of traffic lights.

Road-building didn’t begin until 1967. Before that one traveled by foot or horseback. Bhutan is stunningly scenic, from the yak pastures along the Tibetan border through the flower-laden but treacherous mountain passes. But the eight-hour journey by bus from Thimphu to the Gangteng Monastery over the frightening Central Road is not for the faint of heart. The road clings precariously to the steep gorges, averaging about 17 horseshoe turns per mile.

The Gangteng Monastary itself is perched on the rim of the picturesque Phobjika Valley. The next day I talked with the prime minister, who explained that the valley was in an environmental protection zone under a policy started by the king in 1974.

“After his coronation His Majesty King Wangchuck decreed that Bhutan should keep 60 percent of its forests. We believe that cutting a tree is taking a life. We want to tell the world that environmental protection is a wise policy. Bhutan said no to the oil companies. We want industries, but we will keep agriculture to 8 percent so as not to clear land. Demand on natural resources is going up. How to balance? We must find the middle path. We are developing organic farming using little pesticide. We used to export paper to India for a good price, but in 1999 we banned paper export and decided to forgo revenue to save the trees.”

“Is Bhutan afraid of being taken over by the powerful countries on its borders?” I asked.

“We have overcome that. We are now an established sovereign independent country and a member of the United Nations so we have no fear of India or China. We have diplomatic relations with 21 countries. Relations with India are excellent. We were completely isolated until the 1950s when we opened up and established schools, etc. India helped us. Most of our assistance came from India. We are grateful. Today relations have matured and we have a model relationship.”

What is Bhutan’s biggest problem?

“Our problem is not from without but from within. Bhutan fears the inevitable encroachment of modernization. I believe the major challenge we face today is to balance modernization with the preservation of our values.”

Although Thimphu and other cities have (unreliable) electricity and Internet connections, no signs of modernity have yet penetrated the walls of the Ganteng Monastery. The sparsely populated villages in the lush Phobjikha Valley share communal cold-water taps and no telephones or electricity. But in spite of what Americans would consider primitive living conditions, the people appear vigorous and cheerful. Bhutan is in the process of establishing a new high-tech communications network, but the only satellite dish I saw was surrounded by prayer flags sending protective mantras on the winds. The only electricity in the valley comes from a solar generator in the apartment of the High Lama where I recharged my camera batteries. I asked him if the residents were planning to bring in electricity and got an answer unique to Bhutan.

“This valley is the winter residence of about 300 black-necked cranes from Siberia. It is a wildlife preserve. We don’t want to string overhead lines that would interfere with their migration… we don’t have plans to bring electricity here until we can get underground cables. The cranes take priority.”

We were greeted at the monastery by the Tulku in a flowing saffron robe. He blessed us with white scarves and escorted us through a tunneled portal embossed with enormous murals of the “Twelve Protective Goddesses of the Snowy Mountains.”

The portal led to a flagstone courtyard where we witnessed a scene from medieval times. A dizzying feast of reds, yellows and oranges swirled before us. Saffron-robed musicians in spherical red brocade hats recreated discordant music with drums, cymbals and mournful horns. The sun reflected off the blue and golden brocades worn by thousands of devotees in the audience, dressed in their national costumes. Some had trekked for miles or ridden in horse or tractor carts filled with children and escorted by barking dogs.

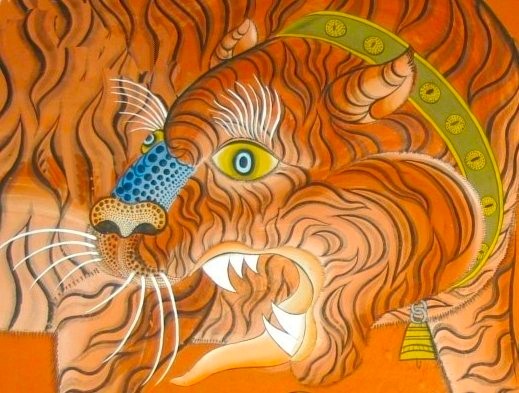

Dancing lamas in animal masks leapt and twirled like whirling dervishes in voluminous yellow and blue skirts performing the dramatic “Dance of the Four Stags.” The dance shows how Guru Rinpoche subdued the God of the Wind and rode off on his stag. It was the first of 12 episodic dance-dramas called Cham to honor Guru Rinpoche – an Indian mystic, Padmasambhava, whom the Bhutanese believe is the embodiment of the historic Buddha Shakyamuni. The dances haven’t changed since they were choreographed 500 years ago. The Tshechu has a dual purpose: The lama dancers make offerings to the Buddha and deities, while the audience receives blessings and empowerment from the dharma, the Buddhist teachings.

Guru Rinpoche is credited with establishing Buddhism in the entire Himalayan region. According to Bhutanese mythology, in the 8th century, the guru flew into Bhutan from Tibet via the kingdom of Swat on the back of a dakini, a kind of female spirit, who took the form of a ferocious tigress, bringing Buddhism to Bhutan. (And if you can’t believe that, don’t go to Bhutan).

The festival climaxes with the empowerment ceremony, which would be a sensation at Super Bowl halftime. The High Lama (Tulku) officiates while other lamas wearing masks to incarnate wrathful and compassionate deities burn fragrant jasmine and monks in swirling yellow and blue skirts dance among the rows and rows of people seated in the lotus position, surrounded by laughing children and dogs. An occasional black goat wandered around gobbling leftover lunches. By the time the sun set into a blazing orange sky, everyone, including me, felt empowered with happiness.