There’s a terrific moment in the musical “South Pacific” — “This Nearly Was Mine” — when kindly French plantation owner Emile de Becque realizes that the love and happiness he longs for and deserves is slipping away. And all because of the blind, stupid, infuriating prejudice of others.

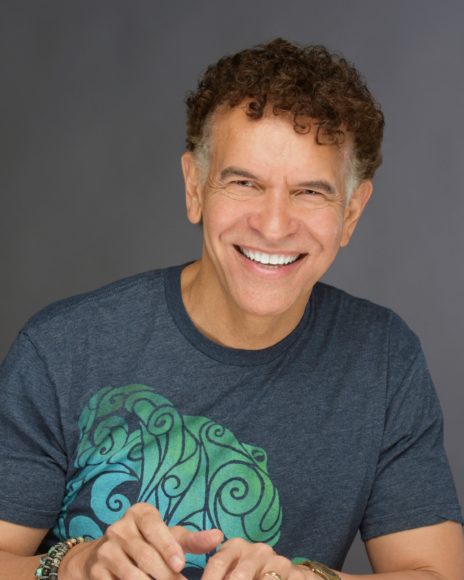

“For me, that’s my favorite song in the show,” says Brian Stokes Mitchell, who played de Becque in “ ‘South Pacific’ in Concert From Carnegie Hall,” which aired on PBS’ “Great Performances” in 2006. “That is the center of the show — that and ‘You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught’” — which is also about the emotional cost of prejudice.

Though he listened to recordings of Italian opera star Ezio Pinza — who originated the role of de Becque in the acclaimed 1949 Broadway production — Stokes, as he prefers to be called, says he wanted to reinvent the character and in particular de Becques’ big number. In rehearsal with music director/conductor Paul Gemignani and then on the concert stage, Stokes sang the song through but then in the reprise, slowed the tempo and sang more softly, offering “a close-up of what’s in (de Becque’s) head” until words, music and emotions accelerated and crescendoed at the end. De Becque may be resigned to love lost, Stokes says, but he is resilient. And in Stokes’ portrayal of that resilience, a hushed audience knew it was in the presence not only of theatrical greatness but of a transcendent experience.

“A song takes you on a journey, the way a poem does,” says Stokes, who’ll bring his artistry to Caramoor in Katonah as part of its summer festival (June 18 through Aug. 19).

Fortunate son

Although Stokes is as well-known on the concert circuit as he is on stage and screen and has visited Caramoor, his July 9 appearance will mark his debut at the Caramoor Center for Music and the Arts, which financier Walter T. Rosen and his wife, the former Lucie Bigelow Dodge, began with musical performances in their Mediterranean-style home in 1946. (Quick to make connections to Caramoor and Westchester, Mitchell notes that his older brother John designed and built examples of the theremin, an electronic instrument in which Lucie Rosen excelled. And Mitchell himself is a big fan of the late Cortlandt Manor composer Aaron Copland (Page 32), whose “Lincoln Portrait” he narrated for a U.S. Marine Band performance that aired on NPR.

“He was a huge influence on my life,” Stokes says, adding that he learned orchestration in part by transcribing such Copland scores as “Billy the Kid” by hand — a skill that would come in handy when he scored and conducted the music for some episodes of the 1980s CBS series “Trapper John, M.D.,” on which he co-starred for its seven seasons. It was a role he landed right at the beginning of his career.

“Man, I’ve been so lucky,” he says, not only in a 40-year career that has taken him from Broadway (“Man of La Mancha”) to Netflix (a new film on the late Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress) but in a family that was able to offer him so much.

He was born on Halloween in Seattle to Lillian Mitchell, an educator, and George Mitchell, a civilian electronics engineer who worked for the U.S. Navy and later served as chief radio officer for the Scripps Institute of Oceanography and Exxon, now ExxonMobil. (Mitchell was also one of the original “Tuskegee Airmen,” an African American unit of the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) during World War II, having taught radio and blinker code at Moton Field, Alabama.)

Young Stokes grew up in Seattle, San Diego, Guam and the Philippines, beginning piano and vocal studies at age 6. Eight years later, he would return to the U.S. to study singing, acting and dancing at the San Diego Junior Theatre. And two years after that, he’d be on San Diego stages before a transfer with a repertory company to Los Angeles — and destiny.

Art and money

Stokes understands only too well, however, that not everyone has been so fortunate. Perhaps that’s why while he speaks passionately about the arts and culture — the words rushing forward, punctuated every now and then by three in particular, “joy,” “joyous” and “joyousness” — there’s a pragmatism to him as well that’s evinced in his roles as a founder of Black Theatre United and chairman of the board of The Actors Fund.

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, Stokes joined with a group of actors, directors, musicians, writers, technicians, producers and stage managers that included Vanessa Williams, Audra McDonald, Billy Porter and Anna Deavere Smith to form Black Theatre United and stand for social justice. The group also met with “producers, directors, union heads, artists,” Stokes says, to discuss not only the portrayals of Blacks in the theater but also the opportunities for them, particularly in the arena of leadership.

“We got into a room and said, ‘We have a problem, and how are we going to solve it? It’s about the business of theater and the message of theater but mostly it’s about the business of theater, because we live in a capitalistic society.’”

We also live in a heterogenous one that is becoming increasingly multicultural, he adds. “What happens to organizations that don’t embrace heterogeneity?” To Stokes, it’s about everyone getting off his high horse to understand the viewpoints of others and perfect a flawed system of government that’s better than most.

That understanding needs to be extended to a theatrical community that for the most part doesn’t consist of stars like himself but gig workers going from job to job, he adds. The Actors Fund offers social services to those in need in the performing artists, be they on camera or stage or behind the scenes — a need that has become greater with Covid.

But as the need for help has increased, so has the theater’s initiatives. Stokes points to efforts like “Stars in the House,” a livestream series hosted by Sirius XM’s Seth Rudetsky and his husband, producer James Wesley, that raises money for The Actors Fund with a talk-performance format. The fund will also host its fundraising gala on May 9 at 7:30 p.m. in New York and Los Angeles.

Man of Manhattan —

and La Mancha

Stokes knows all about Covid. In March 2020, he came down with it.

“It was the worst thing I’ve ever had except shingles — a 105-degree fever, chills. I lost my senses of taste and smell. I could feel it moving around my body.” Jason Kindt, DO, The Actors Fund’s medical director, advised him not to go to a hospital, since no one knew what he was dealing with at that time. So Stokes quarantined away from his wife and son in his Manhattan apartment. When he was strong enough, he began going out on his balcony and singing “The Impossible Dream” from “Man of La Mancha,” in whose 2002 Broadway revival he starred. Inspired by Italians in lockdown, Stokes did this for 2 ½ months to honor essential workers, all the while wondering if he were making it about himself and should quit.

But like the cynical prisoners in “La Mancha,” who are ultimately won over by the troubled Miguel de Cervantes’ tale of Don Quixote’s impossible dream, Stokes’ neighbors urged him on, gathering beneath his balcony to listen. And he realized he wasn’t just singing for an ideal or himself. He was singing for them. It’s what he’s always done.

“Here’s my main thing,” he says, “trying to…let the music come through and bring joy.”

Brian Stokes Mitchell performs songs from the American Songbook at 8 p.m. July 9 at Caramoor Center for Music and the Arts’ Venetian Theater. Tickets begin at $40. For more, visit caramoor.org. And for more on The Actors Fund’s May 9 gala, visit actorsfund.org.

A ‘dynamic’ season

Caramoor’s summer season opens with cellist Yo-Yo Ma & The Knights on June 18 and continues through Aug. 19. Headliners include opera sopranos Stephanie Blythe and Dawn Upshaw; country-blues-old time singer and instrumentalist Rhiannon Giddens with the Silkroad Ensemble; the Trinity Baroque Orchestra in Handel’s “Theodora”; and Michael Gordon presenting his new, experimental, site-specific “Field of Vision” for 40 percussionists.

“This summer is one of the most dynamic in our history,” says Caramoor President and CEO Edward J. Lewis III. “Our incredible lineup of artists and repertoire include voices from an array of backgrounds, eras and lived experiences, reflecting a broad diversity of audiences…. We’re thrilled to present a season of such powerful world-class music experiences in our picturesque outdoor venues.”

Adds Kathy Schuman, Caramoor’s artistic director: “Over the years, Caramoor’s programming has expanded beyond classical music to include jazz, American roots, world music and more, so we’ve already been presenting a diverse slate of musicians. This summer I’m particularly excited to be highlighting many underrepresented artists in the classical realm, who so deserve greater recognition. I hope that their amplified voices and music will be as great a discovery to audiences as they have been to me.”

In addition to Gordon’s “Field of Visions,” other free events include “Soundscapes,” a pre-season program that officially opens the grounds on June 5 with performances by percussive dancers, a beatboxer, and vocal percussionist and a breath artist, as well as a theremin performance, workshops and the opportunity to meet the sound artists and participate in guided tours of the Sonic Innovations exhibit. Caramoor will also celebrate the emancipation of enslaved African Americans with a Juneteenth event marked by its collaboration with the town of Bedford.

For tickets and more, visit Caramoor.org.