When you think of the French Impressionists — perhaps as famous a group of artists as there is today — the name “Alfred Sisley” does not come readily to mind.

ociété anonyme coopérative des peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc. — what was called derisively then and admiringly now the Impressionists. Indeed, he exhibited with Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro and Pierre-Auguste Renoir in their first show, in 1874, and on three subsequent occasions — in 1876, 1877 and 1882. (Other members included Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt, the only American.)

That Sisley is not as celebrated as many of his colleagues says perhaps more about his temperament and the vagaries of fate and fame than it does about his art.

You have to wonder what he would have thought of the just-opened “Alfred Sisley (1839-1899): Impressionist Master” — through May 21 at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich — surely one of the most ravishing shows to come to this area in a long time. Sisley, from a well-to-do British family of shifting fortunes, strove to be entrepreneurial. Indeed, we learn from MaryAnne Stevens’ essay in the coveted accompanying catalog (Bruce Museum/Hotel de Caumont Centre d’Art) that it was Sisley, along with Morisot and Renoir, who organized an auction of the group’s works during a market downturn.

Yet he was a private man with no gift for self-promotion. In a way, his art and his life were metaphors for each other. His success and his limitations lay in his desire to stay within himself.

That was certainly true of his painting, which remained faithful to the original premise of French Impressionism. Not for him the bright lights and boulevards of Pissarro, the pearlescent nudes of Renoir, the flitting dancers of Degas, the domestic drama of Cassatt or the versatile genius of Monet.

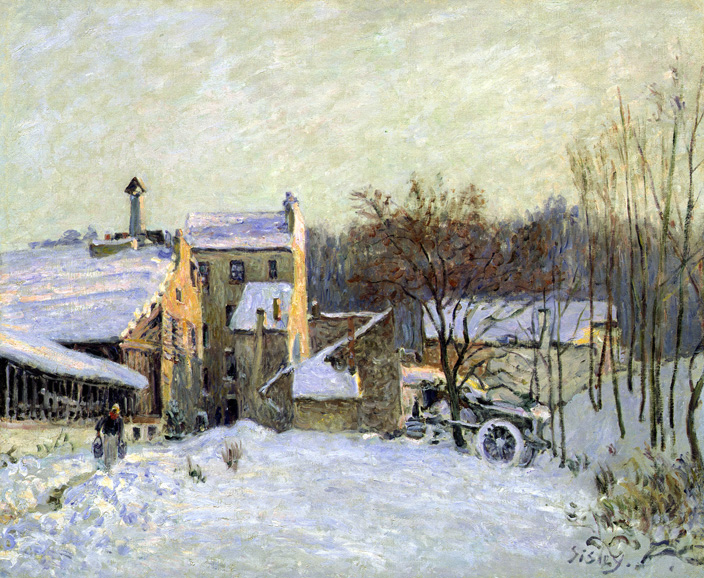

“He was a pure landscape painter whose vision was entirely directed by sky, land and water in all its variety and combinations,” Richard Shone writes in the catalog. In his only writing about his work — no Vincent van Gogh, he — Sisley pronounced the sky the key pictorial element and said that he always began a painting with it. “Boat During the Flood at Port-Marly” (1876) gives us a signature Sisley sky, with patches of ochre, opal and periwinkle reflected in watery shards that also turn a mustard and white building into a shimmery mirage. In “Foggy Morning, Voisins” (1874), the blue, gray, periwinkle sky envelops and tinges trees, fencing, flower beds and even the bent figure of a woman picking blossoms, who, in typical Sisley fashion, remains almost unnoticed in the landscape.

It was no doubt the Sisleyean sky palette that led Shone to declare Sisley — along with Monet — “the great painter of snow.

“Has any other painter suggested so well a sky imminent with snowfall or one that is clearing after rain?”

Some critics have attributed Sisley’s moody palette and reticence to his Britishness. He was born in Paris on Oct. 30, 1839 — the year photography was invented — to a successful textile merchant who sent his son to London in 1857 to learn the family business. But Sisley’s heart belonged to art and Paris, in particular the Forest of Fontainebleau, which Shone calls “the ‘cradle’ of French landscape painting.”

In the 1860s, Sisley studied with Swiss academic painter Charles Gleyre in preparation for the École des Beaux-Arts and exhibition at the official Salon. He also established relationships with those artists who would form the core of the Impressionists.

Sisley lived on the western outskirts of Paris before moving to Moret-sur-Loing, southeast of the Forest of Fontainebleau. These areas, along with three visits to the United Kingdom — including a stop at Hampton Court Palace, a favorite of Henry VIII’s — would inspire him for the rest of his life.

Today, that inspiration is worth millions. But Sisley never saw financial success. His liaison with Breton Eugénie Lescouezec — the mother of his two children, Pierre and Jeanne, and later his wife — led his father, William, to cut off his allowance (although he did try to help him during the Franco-Prussian War). The war itself dealt several blows, destroying Sisley’s home and studio at Bougival and William Sisley’s business, spurring the elder Sisley’s mental instability.

Through it all, the French Impressionist persisted, emphasis on the word “French.” In 1898, a year after marrying Lescouezec in Cardiff, Wales, Sisley applied for French citizenship but was denied. A second attempt was scudded by illness.

Sisley died on Jan. 29, 1899, a few months after his wife, in Moret-sur-Loing. Like the hero of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “HMS Pinafore,” the perhaps quintessential French Impressionist “remains an Englishman.”

For more, visit brucemuseum.org.