“In time you’ll drop dead and I’ll come to your funeral in a red dress.”

— Loretta Castorini to her (former) fiancé, Johnny Cammareri, in “Moonstruck” (1987)

We know the feeling, Loretta. We were once humiliated by a garden gnome of a celebrity gatekeeper — think Truman Capote with a particularly bad comb over — whom we knew we were fated to encounter at a banquet. So what could we do but take ourselves off to The Westchester to purchase a form-fitting red lace cocktail dress for the occasion, one with a low neck and back. And we kept that back to him — or was it our cold shoulder? — for an entire evening as we sat a table away, looking fabulous.

We called it our — well, never mind what we called it. It’s not printable. Let’s just say it was our “drop-dead” dress.

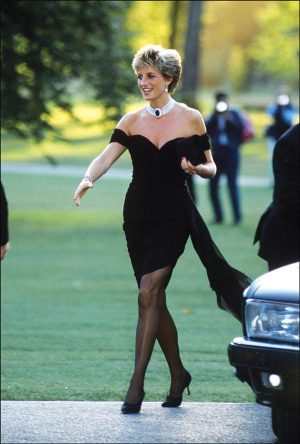

Perhaps the most famous “drop-dead” dress in recent history was the asymmetrical off-the-shoulder Christina Stambolian LBD (little black dress) that Diana, Princess of Wales, wore to Vanity Fair’s summer party in 1994. She had actually had the dress in her wardrobe for three years, considering it too daring to wear. But out of the closet it came for the party, which took place the same night an interview aired with estranged hubby Prince Charles, in which he admitted his adultery with Camilla Parker Bowles (now his wife and Duchess of Cornwall).

What would we have given to see Diana at the May wedding of her younger son, Prince Harry, to the former Meghan Markle, not just because she loved him so but to see what she would’ve worn — something no doubt elegant that nonetheless would not have upstaged the bride.

That wedding was chockablock with fashion statements, which everyone from fashionistas to pundits pored over as if they were biblical texts. There were, to name a few,

• The I’m here-to-support-the-bride-on-a-lovely-spring-day look (Serena Williams in pink Versace; Priyanka Chopra in lavender);

• The I’m-here-not-to-upstage-the-bride-even-though-I’m-the-future-queen-of-England statement (Catherine, the Duchess of Cambridge in a lemon yellow bordering on cream Alexander McQueen coat that she had worn twice before, including to daughter Princess Charlotte’s christening);

• The-I-can’t-help-but-upstage-the-bride-because-I-look-so-hot statement (Lady Kitty Spencer, Prince Harry’s cousin, in head-turning forest green Dolce & Gabbana with a floral border);

• The I’m-here-to-be-noticed-along-with-my-self-satisfied-husband-even-though-we-have-no-familial-ties-to-the-royals look (Amal Clooney in goldenrod Stella McCartney with a matching flying saucer on her head);

• The I’ve-made-mistakes-in-the-past-but-today-I’m-the-picture-of-propriety statement (Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, in a smart navy dress with pink piping by Windsor-based Emma Louise Design); and

• The I-didn’t-get-the-pastel-memo-and-anyway-I’m-a-winter look (Countess Karen Spencer, Prince Harry’s aunt, in shapely but off-season purple).

And then there was the bride herself, a goddess in demure but glamorous Givenchy (and later a sexy white Stella McCartney halter gown), the deus ex machina in the fairy tale that ends “Harrily” ever after.

With the exception of Harry and Prince William in the frockcoat uniforms of the Blues and Royals, does anyone remember what the men wore to the wedding? Mostly morning coats. It’s not that men haven’t been fashionable or made fashion statements since the dawn of discernible fashion (around the 14th century in the West). It’s that they have for the most part ceded that role to women — along with beauty and sex appeal — in exchange for power. Indeed, when we think of male fashion statements, we think of the early 1950s rebels in their uniform of white Ts and blue jeans — with Montgomery Clift, adding a bomber jacket; Marlon Brando, a motorcycle one; and James Dean, a red windbreaker.

For the most part, though, fashion has been female and occasionally fraught, particularly for the small group of women who become first ladies. From Nancy Reagan’s “donated” red Adolfo suits and gowns to Barbara Bush’s granny pearls to Hillary Clinton’s ever-evolving hairstyles and headbands, the first lady’s looks and actions are endlessly parsed, as if there were special meaning in the cut of a blouse or the color of a pantsuit. Because there is.

Melania Trump watchers certainly seem to think so as they divine each outfit. Was the pussy bow blouse she wore to one presidential debate a sign of solidarity with the Pussyhat movement, a comment on her husband’s infamous “Access Hollywood” tape or both? Did the white pantsuit she wore to the president’s State of the Union address earlier this year hold a message for the women’s movement, whose suffragist ancestors took white as their color? Who actually was the intended audience for the olive “I REALLY DON’T CARE, DO U?” Zara jacket Trump wore on the plane to the southern border but not to her actual meeting there?

In a recent piece in The New York Times, Vanessa Friedman — the paper’s fashion director and chief fashion critic — noted that Trump seems to have reversed the first lady’s fashion role, which is to be unassuming in a crisis at home and vibrant in overseas diplomacy. Unlike the “I REALLY DON’T CARE” jacket, Trump’s choices for the president’s explosive recent trip to Europe were elegant but safe, Friedman wrote. A possible exception was the pale yellow J. Mendel goddess gown with the attached cape she wore to the state dinner at England’s Blenheim Palace, which some in the Twitterati likened to Belle’s ball gown in Walt Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast.”

After the brouhaha over jacket-gate, the first lady’s communications director, Stephanie Grisham, took a page out of Sigmund Freud, who reportedly once remarked about dream symbolism: “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.”

“It’s just a jacket,” Grisham told reporters.

Except that when it comes to women, clothes and gesture politics, it rarely is.