Polka dots. Pumpkins. Pumpkins with polka dots. And trees with polka dots. Don’t forget the trees wrapped Christo-like in polka-dotted mesh. Plus, Polka Dot Picnics and Pumpkin Power Weekends, along with immersive infinity mirror installations.

The Bronx will be even more of a happening place this spring as the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) presents “Kusama: Cosmic Nature” (May 9-Nov. 1), a multimedia exploration of the legendary 90-year-old Japanese artist, whose work fuses the aesthetic and the organic, the infinitesimal and the infinite.

In announcing the exhibit, NYBG CEO and President Carrie Rebora Barratt called Yayoi Kusama “an artist for our time and our place, taking her cue from our planet and all that matters to us in our world.”

Just how timely the artist has become was evident in 2017 when some 160,000 art lovers snaked around the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. to spend a half-minute in each of six “Infinity Mirror” installations — a phenomenon that drew the national press, including “PBS NewsHour’s” chief arts correspondent Jeffrey Brown. (Expect more of the same when the Hirshhorn opens another Kusama show April 4.)

For the NYBG exhibit, Barratt said there will be two different types of tickets, one of which will include timed access to the “Infinity Mirrored Room — Illusion Inside the Heart” — an immersive outdoor installation responding to the ever-changing daylight and seasons — to ensure everyone has his experience of both the fleeting and the eternal.

Melding art and nature

“Infinity” is just one of four new works, including “Flower Obsession,” the artist’s first-ever “obliteration” greenhouse, where visitors can cover the interior with coral flower stickers; “Dancing Pumpkin,” a dynamic 16-foot-tall bronze painted in Kusama’s signature yellow with black polka dots; and “I Want to Fly to the Universe,” a bright 13-foot-high sunflower-like form with a yellow face and, yes, polka dots.

To accompany the intense design aspect of Kusama’s work, the garden will create a rich patchwork of flora that will also respond to the seasons as bulb plants like daffodils, irises and tulips as well as blossoming fruit trees give way to roses, day lilies and hydrangeas and ultimately to pumpkins and kiku (for “chrysanthemum,” Japan’s harbinger of the fall). On the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory lawn, “Dancing Pumpkin” will boogie with river birches, flowering plants, grasses, ferns and whimsical topiary. (In the pas de deux between art and nature, Barratt said, no botanical would be harmed.) “Hymn of Life: Tulip” (2007), made of three outsized fiberglass flowers, will commune with the conservatory courtyard pool’s water lilies. Inside the conservatory’s exhibit galleries, “Starry Pumpkin” (2015), festooned with pink and gold mosaic, will have pride of place in a similarly colored woodland garden of flowers and foliage, while “Alone, Buried in a Flower Garden” (2014) will serve as a blueprint for a changing arrangement of plantings, separated by river rocks, to replicate the painting’s bold shapes and palette.

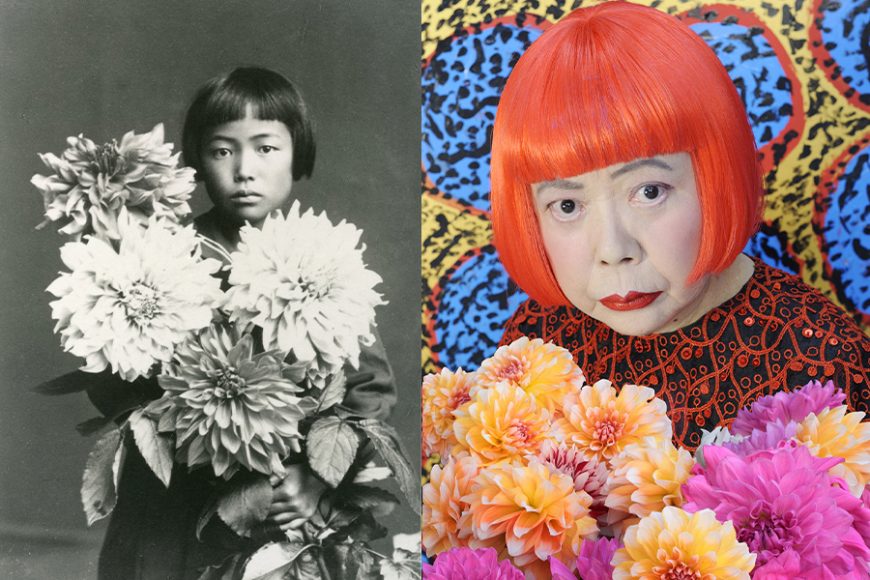

Across the 250-acre campus, the Library Building will feature an array of Kusama’s botanical sketches, paintings, works on paper, biomorphic collages, assemblages and recent soft sculpture and canvas works that consider the infinite variety of floral structures — a theme addressed in the magnified images of plants viewed through electron microscopes in the library’s Britton Science Gallery. In the library’s “Life” (2015) installation, visitors will navigate a circular space enclosing polka-dotted forms with mosaic surfaces. In “Pumpkins Screaming About Love Beyond Infinity” (2017), they’ll encounter a mirrored cube reflecting an infinity of polka-dotted pumpkins. It’s accompanied by a statement in which the artist describes the pumpkin as “beloved of all the plants in the world. When I see pumpkins, I cannot efface the joy of them being my everything, nor the awe I hold them in.” If it’s true that you grow to resemble what you love, Kusama looks like her adorable pumpkins, with her flame-colored, Louise Brooks-bob of a wig and matching attire.

Mystical connections

Kusama’s love of art and nature was born in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, Japan, where she grew up in a rich but troubled family of merchants, who owned a plant nursery and seed farm. Like the artist Louise Bourgeois, Kusama was forced to become a go-between in her parents’ adulterous marriage, which in Kusama’s case meant spying on her father and his various lovers for her mother.

From an early age, she escaped into an art that was heightened by her hallucinations of light, auras, fields of dots and talking flowers, which would become the key elements in her works. It was as if she was looking to become lost in them. She refers to her art as “self-obliteration,” and indeed a drawing she did as a 10-year-old of a woman in a kimono presumed to be her mother shows the subject engulfed in dots.

At 13, Kusama was sent off to a military factory to make parachutes for the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, which she would later describe as a period of darkness. After the war, she studied traditional Japanese painting at the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts. But Kusama was increasingly drawn to the avant-garde styles of the West and, after initial success in Japan, she moved to New York City in 1957.

Over the next 15 years, she would establish herself at the forefront of the avant-garde — befriending artists like Donald Judd, Eva Hesse and, especially South Nyack’s reclusive Joseph Cornell, who gave her many of his Surrealistic assemblages. She also explored sex, sexuality and political protest in happenings that often involved nudity. While these gained her fame, they distressed her family and this, coupled with her inability to sell her work — which was often successfully copied by men — led her to two suicide attempts.

In 1973, she returned to Japan, took up fiction and autobiography, became an art dealer briefly and checked into Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill, where she continues to live voluntarily, not far from her Tokyo studio. (The city is also home to the Yayoi Kusama Museum, a hotspot since its opening in 2017.)

In the 1980s, Kusama’s art career continued to simmer, but she would soon turn up the heat. At the Venice Biennale in 1993, she blazed, presiding over a mirrored room filled with her beloved pumpkin sculptures. In the new century, her polka dots would adorn everything from cellphone cases to Lancome lipsticks to Louis Vuitton and a collaboration with Marc Jacobs, who once said, “I don’t think there is ever a wrong time for polka dots.”

Or indeed for Kusama.

For tickets and more, visit nybg.org/kusama.