Timothy J. Rooney was destined to be president and CEO of Empire City Casino at Yonkers Raceway. Indeed, he owes his very name to horse racing.

One of the stories told about the legendary Rooneys – his father, Art, founded the Pittsburgh Steelers, which the family still owns – concerns a bet that Art made around the time the third of his five sons was about to be born.

“In those days, you placed your bet with a bookie, like they do in England and Ireland,” Timothy Rooney says. Art placed this one with a friend and leading bookmaker – Tim Mara, who was also owner of the New York Giants. The bet paid off big, thanks in part to a tip Tim had given him, so Art honored him by naming his third son Timothy.

It was the beginning of what we might call Six Degrees of Timothy: Tim Mara had a son named Wellington Timothy Mara, who succeeded his father. Wellington had a Timothy, too – Timothy Christopher “Chris” Mara, the Giants’ vice president of player evaluation, who married Timothy Rooney’s daughter Kathleen. Among Chris and Kathleen’s children are the actresses Kate Mara, who appeared in the acclaimed series “House of Cards,” and Rooney Mara, who broke through in “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.”

“I see most of their films,” says their proud grandfather, who’s looking forward to catching Rooney Mara’s turn in the Oscar-winning “Her” when it comes to DVD. “I enjoy them very much. They’re very talented and they’re interested in working with all the great producers and directors to learn as much as they can. They’re diligent. And that’s absolutely essential no matter what field you’re in.”

Family is key to Rooney.

“I really think our successful background comes from our parents. You learned respect for others, honesty, loyalty.”

It wasn’t just his father who instilled these values but his mother, Kathleen.

“She was very funny and quick-witted with a lot of old Irish sayings.” She would say, for instance, that someone was “so proper he’d wear a riding hat to eat horseradish.”

Timothy Rooney has his mother’s silver tongue. He’s an easy conversationalist, who can flow from Triple Crown winners to pizza parlors (try Johnny’s Pizzeria in Mount Vernon, he says) and conjure images of an underage kid so in love with horses that he’d sneak under a fence or hang out by a barn to catch the racing action. When the Rooney family bought the raceway in 1972, he was a natural to run it. (Timothy Rooney no longer has any stake in the Steelers as the NFL stipulates that team owners cannot have gambling interests.)

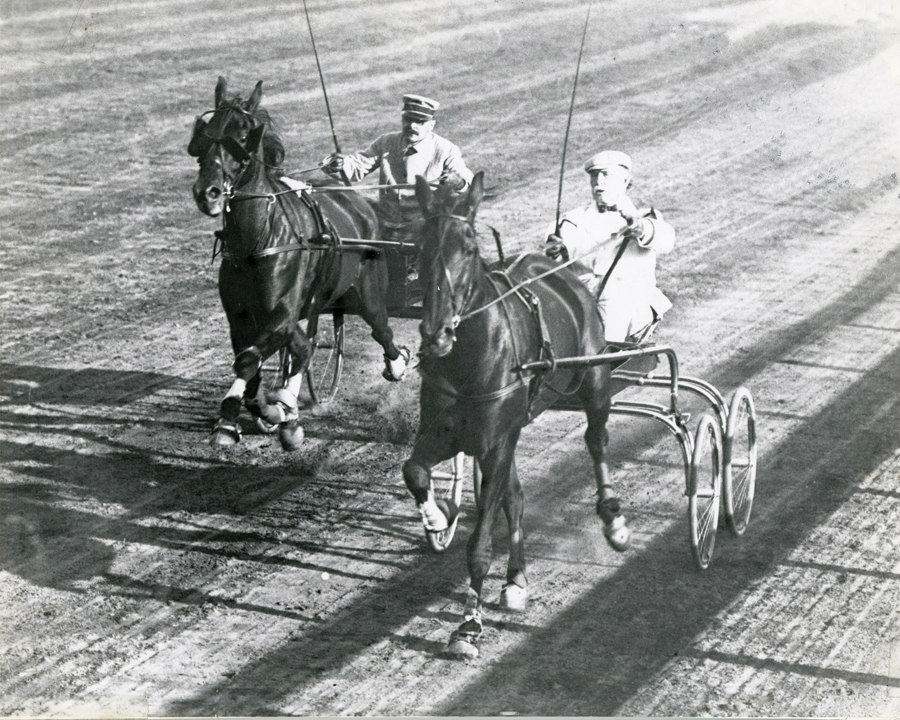

By then the raceway had seen a lot of history. A Yonkers landmark, the track began with harness racing when William H. Clark opened it as the Empire City Trotting Club in 1899. When he died a year later, the track went dark except for events like the 1902 car race in which Barney Oldfield, driving the Ford “999,” set a one-mile record with a time of 55:54 seconds.

New York grocery titan James Butler would return the other kind of horse power to Yonkers, reopening the venue in 1907, this time for Thoroughbreds like Seabiscuit, who took the Scarsdale Handicap in 1936 on his way to his eventual victory over War Admiral.

The track returned to harness racing in 1942. Eight years later, the Algam Corp., headed by William H. Cane, turned the site into Yonkers Raceway.

The turbulent ’60s saw a decline in harness racing’s popularity and in the raceway, though the diehard fans still came. Rooney can remember looking up at the bank of TVs on the pillars of the grandstand the day in August 1974 that President Richard Nixon resigned. Every TV carried Nixon’s image. And every bettor had his eyeballs glued to his program.

Rooney is not like that. “I very seldom make a bet, except for the Breeders’ Cup and the Ascot, which I go to every year.”

But he is fascinated by breeding, bloodlines and equine evolution.

“The interesting thing is that Thoroughbreds’ speed has not dramatically changed, although they are faster now. But the speed of the harness horses has evolved in the past 50 years.”

Back then, Rooney says, a good harness horse, or Standardbred, might run the raceway’s one-half-mile dirt track in 2:05. “If a harness horse did 2:05 today, you’d be giving him away to the Amish or maybe to Mayor (Bill) de Blasio” – a reference to the New York City mayor’s plan to do away with horse-drawn carriages in Central Park.

Faster turns and lighter bikes (the carts the drivers sit in) are among the contributors to the greater speed. But the evolution of the harness horse is probably nothing compared to the change Yonkers Raceway has undergone. The track moseyed along in the 1990s, welcoming flea markets and the annual Westchester County Fair. There were cosmetic effects as well. The finish line was moved in 1996 to the end of the stretch, increasing the length of the stretch from 440 to 660 feet. A year later, the grandstand was demolished.

Then in 2001, New York state authorized slot machines at eight racetracks, including Yonkers Raceway, paving the way for a $225 million renovation by EwingCole. The original six-story clubhouse was refurbished to accommodate slots and restaurants on the first two floors. A one-story building was added to hold additional video gaming machines, a food court, bars and an entertainment lounge. (Under state lottery laws, you must be at least 18 to play any of the 5,380 slots at Empire City, not to mention video roulette, electronic craps, Sic Bo and the holographic baccarat games that are expected to go live at the end of May.)

Rooney calls the state’s decision “the most dramatic effect. Without the slots, Yonkers Raceway would’ve become a shopping center.” The proof of the turnaround: During the first week of its October 2006 opening, the raceway netted $3.8 million, streaking by its nearest competitor, Saratoga Casino and Raceway, by two-thirds.

A year ago, Empire City Casino unveiled a $50 million, 66,000-square-foot expansion that relocates 700 slots and video table games; includes two new restaurants – Dan Rooney’s Bar and Café and Pinch; and features a new, high-tech entrance, a 300-foot curved glass wall and a 30,000-square-foot modern gaming floor crowned by artwork of the Manhattan skyline.

The raceway remains home to the Messenger Stakes, one leg of the Triple Crown of Harness Racing for Pacers; the Yonkers Trot, a leg of the Triple Crown for Trotters; and the Art Rooney Pace. But when Hurricane Sandy hit, it was transformed into a hub for Con Edison to distribute dry ice and blankets.

Meanwhile, Timothy Rooney dispatched the Empire City culinary team to serve hot meals to first responders and residents in hard-hit areas, donated $500,000 to the Catholic Charities Hurricane Sandy Relief and Recovery Fund and a $100,000 matching grant to the Empire State Relief Fund.

Rooney, who divides his time between Westchester and Florida, says at first he wasn’t aware of the depth of the tragedy. When it hit him, he hit the ground running.

“With so many people devastated,” he says, “anyone in a position to help had to help.”

Art and Kathleen would’ve expected nothing less.