Photographs courtesy The New York Botanical Garden.

When we think of Frida Kahlo, we tend to think of a life (1907-54) that was as dramatic as her paintings — the bus/trolley car accident that left her body broken and unable to bear children; the volatile marriage to muralist Diego Rivera; the love affairs with men, women and Communism.

Among the less-considered facets of that life was a complex relationship with the natural world that spurred her to go hiking as a child in her native Mexico, learning the proper names of the plants she encountered along the way; to fill the garden of the Casa Azul (Blue House), her home outside Mexico City, with cacti and other succulents; and to paint nature as a metaphor for the balance in duality that she sought.

It is this aspect of the painter that The New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx celebrates in “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life” (May 16-Nov. 1), its latest multidisciplinary blockbuster. Past exhibits have combined elements in the garden’s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory and LuEsther T. Mertz Library “to tell the story of people whose connection to gardens may be little-known or unknown,” says Todd Forrest, The Botanical Garden’s Arthur Ross vice president of horticulture and living collections. This program of shows began with naturalist Charles Darwin in 2008 and continued with poet Emily Dickinson and painter Claude Monet.

It’s safe to venture, however, that at a time when immigration has been in the news and when Hispanics have become an increasingly vital part of American culture, “Frida Kahlo” may prove to be the most popular of these exhibits to date, with “Frida al Fresco” evenings of Mexican music, drinks and food, a Poetry Walk studded with the words of 20th-century Mexican bard Octavio Paz; a symposium on Kahlo, Rivera and 20th-century Mexican art; a Mexican film festival; a companion book; a scavenger hunt; an interactive puppet theater; cooking demonstrations; and botanical science activities.

Though biography is a key influence on any artist’s life, this is not a biographical exhibit.

“We’re not overemphasizing her biography,” says guest curator Adriana Zavala, associate professor of modern and contemporary Latin American art history and director of Latino Studies at Tufts University. “There are definitely autobiographical elements, but if we focus on her biography, we limit our understanding of her imagination. What we’re focusing on is the relationship of the plant world to her creativity.”

That exploration is a two-pronged approach — a reimagining of her garden and studio at the Casa Azul (now the Museo Frida Kahlo) in the conservatory by Tony Award-winning scenic designer Scott Pask and an exhibit of 14 paintings and works on paper in the Mertz library.

The Casa Azul, where Kahlo grew up the daughter of a German father and a mother of Spanish-indigenous ancestry, came into its own, Zavala says, when Kahlo returned there in 1939. (Rivera, with whom Kahlo had a turbulent open marriage, paid the taxes on the house; she retained the title, Zavala says.) With the help of servants, Kahlo transformed her childhood home from a pale gray country house to what Forrest calls “this glorious color palette” of cobalt-blue walls with pale orange, red and pale green touches. The Mediterranean-style garden of roses, violets and orange trees underwent a similar metamorphosis, giving way to agave, barrel and old man cacti, donkey’s tail, calla lilies and bougainvillea. (The garden today is different yet again — more tropical than desert — as trees planted in Kahlo’s childhood have grown tall, requiring shade-bearing plants.)

Over two years, exhibit organizers visited the Casa Azul and neighboring sites, poring over “an archive of photos that’s not out there in the world,” says Karen Daubmann, associate vice president for exhibitions and public engagement:

“There’s Frida in the garden with her animals (including spider monkeys and a pet deer), with Diego. We see the sense of place that small space was in her life.”

The exhibit team also took thousands of photos, Daubmann says, so that it could transfer her love affair with nature — which also manifested itself in the nature books in her library, the flowers embroidered on her native dress and woven into her braided hair — into what the viewer sees.

In the conservatory, that means the garden of Kahlo’s maturity, complete with a scale reproduction of the Aztec-style pyramid that Rivera created for his pre-Hispanic art collection. (In the conservatory, the pyramid will showcase terra-cotta pots containing cacti and other succulents.)

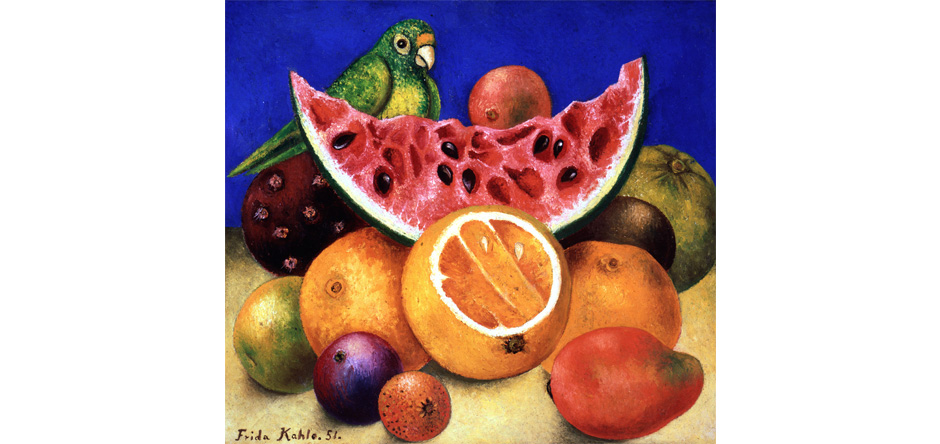

Over at the Mertz library, viewers will encounter the well-schooled Kahlo, steeped in art history, whose paintings and works on paper display what Zavala calls “the dualism of opposites — industry and nature, Europe and indigenous society, men and women.”

And two more pairs of mighty opposites — life and death, pain and joy.

In “Portrait of Luther Burbank” (1931, oil on masonite), inspired by Kahlo’s visit with Rivera to the tree that is the gravesite of the botanist, Burbank’s body becomes the roots and trunk of a tree. As he holds one of his hybrid plants, he, too, becomes a hybrid. It’s a Surrealist fantasy that has its antecedents in art history’s diverse portrayals of Daphne — the classical nymph who prays to be transformed into a bay laurel to elude Apollo’s advances.

In “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” (1940, oil on canvas), the lush backdrop of nature that includes one of Kahlo’s beloved spider monkeys and cats — suggesting the dreamlike work of Henri Rousseau — contrasts with the Christ-like crown of thorns that becomes a piercing, bloody statement necklace.

“Life giving way to death. Death giving way to life,” Forrest says. “It’s nature as complex.”

For more on “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life,” visit nybg.org.