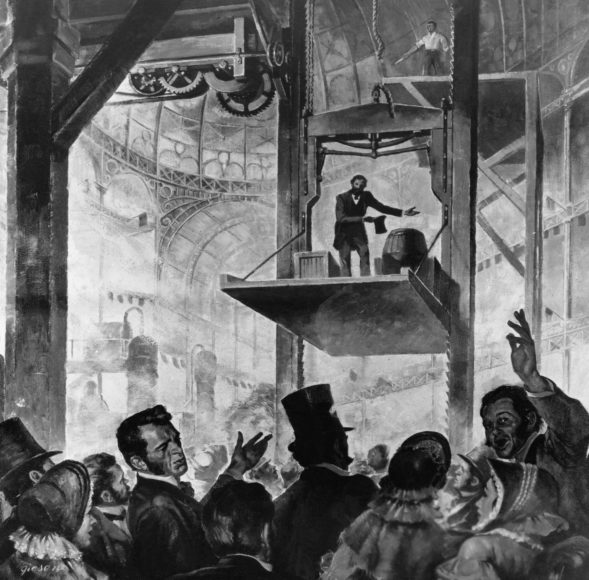

“All safe, gentlemen. All safe.”

That was what Elisha Otis said, showing off his new safety elevator at the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in 1853 in Manhattan.

He had shocked crowds by getting up on a lift platform, which had often been used at the time by manufacturers in factories and warehouses, and ordering it raised to full height. When the rope holding the lift was cut with an axe, the crowd saw the lift locked in place, and that Otis remained unharmed.

It was a key moment not only for the Otis Elevator Co. — which had only seen a few orders come in after opening in Yonkers in 1853 — but also for the development, economies and people of cities everywhere.

Elevators had existed before, as far back as ancient Greece and Rome, but they were not always safe for passengers.

“One problem continued to trouble the elevator as it had since ancient times,” says Ed Jacovino, a spokesperson for Otis, now headquartered in Virginia Beach, Virginia. “There was no effective way to prevent the hoist from plummeting to earth if the lifting cable parted. This ever-present danger made elevators a risky proposition until 1852 with Otis’ invention of the safety elevator.”

The exposition took place at the current site of Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan, which is now, of course, a landscape surrounded by New York City’s signature feature, the skyscraper. An architectural development that changed cities the world over, the skyscraper wouldn’t have been possible without Otis and his invention or other technologies like the steel skeleton frame, courtesy of Chicago architect William Jenney. They enabled the skylines of New York and other cities around the world to soar beyond six stories. (It’s a lesson driven home recently on PBS’ “Impossible Builds’” profile of “the Skinny Skyscraper,” as Manhattan’s Steinway Tower is known. Rising 84 stories, or 1,480 feet, above the preserved, historic, 16-story Steinway Building, the residential tower, the skinniest skyscraper in the world, would not have been possible without the ingeniously stacked Otis passenger-freight elevators.)

After Otis’ demonstration of the safety elevator at the New York Crystal Palace, the company’s sales began to climb. In March of 1857, Otis’ first commercial passenger elevator was installed on Broadway and Broome Street in Manhattan at the E.V. Haughwout and Co. department store, which paid $300 for the device.

“By the 1870s, there were 2,000 Otis elevators in service as elevator safety and efficiency improved, and high floors became desirable real estate,” Jacovino said. “Other big breakthroughs include Otis’ introduction of the hydraulic and electric elevators as well as the gearless traction elevator, which made skyscrapers possible, (and) Otis’ creation of the first elevator system to use flat belt technology in place of steel cables.”

Otis elevators are now in eight of the 10 tallest buildings in the world and such other New York landmarks as the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building and the United Nations. You can find them at the White House, the Eiffel Tower and the Vatican as well.

Along with its global influence, however, Otis Elevator Co. was also a major player in Yonkers and its development through the years. Originally, Otis had settled in the city to work for the Bedstead Manufacturing Co., Jacovino said, the Bergen County, New Jersey-based company that had first asked him to design a freight elevator for its new Yonkers factory. After financial problems led the company to close its doors, Otis opened his own shop in part of the old Bedstead plant.

The Otis plant in Getty Square was one of the largest manufacturing plants in the city and a key to the area’s industrialization, at its peak employing more than 1,300 people, according to a 1982 New York Times report. In 1976, Otis was acquired by United Technologies and became its subsidiary. Business percolated for a time, but in 1983, United decided to close the plant and lay off its 375 workers. United cited a decrease in demand as a reason for pulling out of Yonkers operations, along with changes in technology that the Yonkers plant was not well-suited to meet. The equipment that had been manufactured there would continue being made in Otis’ plants in Bloomington, Indiana, and Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

The factory that had been so critical to Yonkers and its modernization of Getty Square left behind broken hearts — and angry politicians as the area was heavily funded by the Yonkers Industrial Development Agency (IDA).

Otis spun off on its own to become an independent company once again in 2020, as United also spun off its other subsidiary, Carrier, and then merged with Raytheon. But the elevator company never returned to Yonkers.

Today, however, the former Otis complex is home to the nine-story, quarter-mile-long iPark Hudson, purchased in 1999 and developed throughout the years by National Resources, a Greenwich-based real estate company with a penchant for rehabilitating old manufacturing facilities.

Modernization has been bringing new powerhouse companies to the property and as a result, to Yonkers’ economic landscape, offering updated facilities in a setting more affordable than companies might find in New York City. National Resources has even added residential apartment options to the space.

Lionsgate is a major commercial occupant — (Page 18) — adding more than a touch of Hollywood glamour to the site. Other occupants include the State Department of Motor Vehicles, Mindspark, which transforms learning through community and industry partnerships, and ContraFect, which develops biologic therapies to treat life-threatening, drug-resistant infectious diseases.

And while most of the new developments at the plant look toward the future of industry, a major iPark tenant, Kawasaki Rail Car Inc., calls to mind the history of the space. Kawasaki purchased its 239,000-square-foot factory at iPark from National Resources for $25 million in 2012 and continues to build the railcars that are used by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) Metro-North Railroad, the New York City subway system and the Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corp. (PATH).

So while Otis is gone, its former space still hosts major commercial development in Yonkers that is helping to position the city for a brighter future.