It is one of the most famous businesses in the world — a British multinational corporation, headquartered in Manhattan that specializes in everything from wines to watches to Whistlers.

So it’s no surprise that Sotheby’s should launch a luxury real estate company in 1976. Gotta have a place, after all, to display all those treasures. That addition has helped make Sotheby’s one of the largest brokers of, well, stuff on the face of the earth, with 90 locations in 40 countries and art sales alone in the billions.

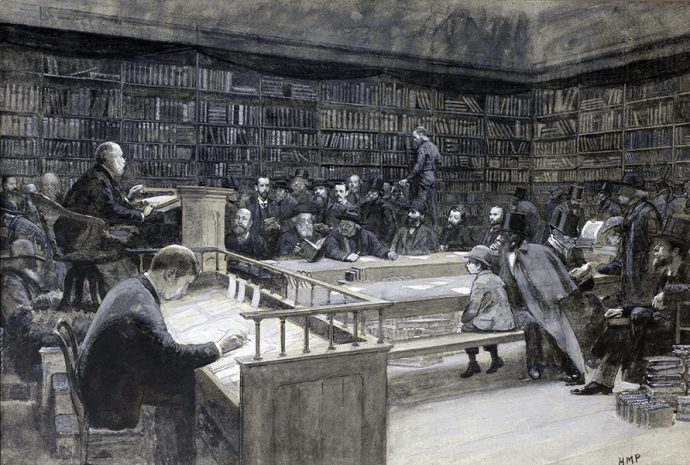

Not bad for a business that began in 1744 in London as Baker and Leigh. (First auction — several hundred rare books from the library of the baronet John Stanley.) Samuel Baker died in 1778, leaving his estate to partners George Leigh and John Sotheby. They continued as book dealers, even auctioning the library Napoléon took with him into exile on the island of St. Helena. It was the Sotheby family that broadened the auction house’s interest to include prints, medals and coins. Fine art wouldn’t enter the picture until 1913 when the auction house sold a Frans Hals for 9,000 guineas. Four years later, Sotheby’s moved to its present London home, 34-35 New Bond St. The U.S. office, at Bowling Green, wouldn’t follow until 1955.

The 1980s proved a turning point for the company. A sales slump spurred the North American flagship’s 1982 move to 1334 York Ave., now Sotheby’s world headquarters. A group of investors led by developer Alfred Taubman bought the company a year later, privatized it, incorporated it as Sotheby’s Holdings Inc. and then took it public in 1988, making it the oldest company to be traded on the New York Stock Exchange. In 2006, Sotheby’s Holdings Inc. was reincorporated as Sotheby’s.

Over the years, Sotheby’s — whose offerings range from private sales to corporate art and museum services to an Institute of Art that is a graduate school of art and its markets — has had its share of scandals (price-fixing, illegal antiquities) and successes. Nothing has grabbed headlines the way the record breakers do, like the version of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” that sold at Sotheby’s for almost, yes, $120 million. (Wonder if the guy in the painting is holding his hands to his ears screaming, “Oh, no, someone just paid $120 million for me.”)

For sheer international interest, few sales could top the four-day April 1996 extravaganza that was the auction of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ estate. Everyone from the tabloids to The New York Times to the major networks thronged York Avenue, working their notepads and flip-top phones — this being before the internet took off. The press was roped off to the side of the main auction room, craning and straining to catch the action. The first night ended on a note of high drama as the bids for John F. Kennedy’s humidor — an inaugural gift from comedian Milton Berle — went for an unheard of $520,000 to Marvin R. Shanken, the New Haven-nurtured editor and publisher of Cigar Aficionado magazine.

The whopping and hollering sounded like Yankee Stadium. It probably could’ve been heard at Yankee Stadium and was yet further proof that Sotheby’s is like no other place in the world.

For more, visit sothebys.com.

I could not have requested a more honest article reported exactly as I told it