“Gardens are good for the soul,” New York City public garden designer Lynden B. Miller observes in the newly released documentary “Beatrix Farrand’s American Landscapes.”

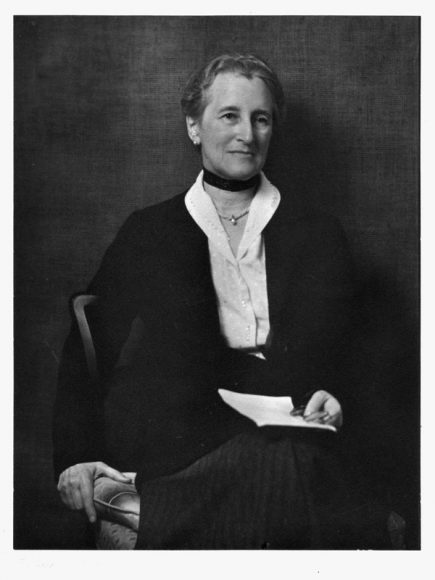

Narrated by Miller, the film charts the life and career of America’s first female landscape architect (1872-1959), who designed gardens for the private estates of East Coast society and served as a consultant for some of the country’s most prestigious private universities and colleges. The film features several of her best-known extant public masterpieces, including the Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden in Seal Harbor, Maine, and Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C.

Garrison resident Anne Cleves Symmes — one of the producers of the film and the current garden educator for the Beatrix Farrand Garden Association at the Bellefield mansion in Hyde Park — spent 20 years leading the team that restored the property’s Farrand garden (built in 1911-12 for her cousin Thomas Newbold and his wife, Sarah). The garden is on the property of the Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site on Route 9 in the Dutchess County town.

“I’ve always been so in love with Farrand and amazed by her career, both as a pioneering woman and as innovator in the field of planting design,” Symmes says. “She broke down barriers and did work that women had not been able to do, and she really advocated and believed in the importance of public landscapes and parks.”

Symmes’ husband is Stephen Ives, founder of the historical documentary film company Insignia Films. “I said to Steve over and over, ‘We’ve got to make a movie about Beatrix Farrand. She’s such an incredible person and everybody needs to know about her legacy,’” Symmes recalls. “He hemmed and hawed, because he worried that we didn’t have enough archival material and there were no moving images of her. He was afraid it wasn’t going to have that certain dynamic.”

That all changed when Miller came to Hyde Park to lecture on how Farrand had mentored her in her career in public horticulture and garden design. Among her many projects, Miller oversaw the restoration of Central Park’s Conservatory Garden. “Lynden did such a dynamic and wonderful talk that Steve fell in love with her and said we could do the film through her eyes and through her journey to learn more about Farrand,” Symmes says.

The film, which took three years to produce, begins with Farrand’s early life. She grew up in high society — Edith Wharton, the novelist and stiletto-sharp chronicler of the 1 percent of the Gilded Age, was her aunt — and came from a family of five generations of garden lovers. Her own passion for it was born at age 11 when her parents bought a house on Mount Desert Island off the coast of Maine.

“Farrand grew up treasuring the property’s little woodland plants and was always digging them up and bringing them close to the house to add to her own gardens,” Symmes says.

Farrand was determined to pursue a career in horticulture, a challenge since the profession was not open to women. No universities would take her, so she studied privately with Charles Sprague Sargent — one of the foremost botanists of his day, who was the first director of The Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University and a cousin of the Gilded Age portrait painter John Singer Sargent. She then hired a tutor from the School of Mines of Columbia University to teach her surveying skills.

In 1895, Farrand went on a five-month trip with her mother to visit almost 150 gardens around the world, from Versailles in Paris to the Jardin d’Essai in Algiers.

“What makes Farrand stand out is the way she was able to combine styles and to bring ideas from Europe — including Italian and French gardens — and mix those with the wild gardens and landscape gardens of England as well as the Hudson River tradition of romantic landscapes,” Symmes says. “She took all those influences and combined them in new ways, and she was a big champion of native American plants.”

In 1916, she started work on what became New York Botanical Garden’s Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden.

“Farrand designed the Rose Garden with a natural, beautiful plan in a triangular form and with great

attention to the scientific layout. She grouped the roses by families, with wilder roses farther out than those in the more formal structure,” Symmes says.

Farrand was up against a difficult time, because while botanical garden board members were excited about her ideas and plans, they had a lot of difficulty raising the money to bring them to completion.

“She had these amazing iron gates, a pergola and all these wonderful support structures for the roses. None of that could be built because there were no funds,” Symmes says.

In 1988, David Rockefeller, the youngest of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s six children, made a donation in honor of his wife Peggy — a horticulturalist and conservationist who adored roses — that enabled the rose garden to be completed. It has gone on to become an important teaching garden, featuring many new roses that hadn’t been cultivated in Farrand’s day, along with old-fashioned roses that she would have been very familiar with. “It’s a recreation of her original design in terms of the structure of the garden, but it now features a modern curation of some 650 different varieties of roses,” Symmes says.

For the Dumbarton Oaks estate of American diplomat Robert Bliss and his wife, Mildred, now an historic site in Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown neighborhood — Farrand designed the gardens covering their hilly, 53-acre property, which featured a 100-foot descent down to Rock Creek. Beginning in 1921, Farrand worked closely with Mildred Bliss for almost 30 years to achieve their vision of terraced gardens and vistas, orchards and kitchen gardens and an array of meadows and wooded pathways. They also collaborated on the design and choice of the garden’s ornaments, from benches and gates to finials and sculptures.

With all its retaining walls and terracing, it was a complex engineering feat and an opportunity for Farrand to incorporate many of the styles and influences that she had absorbed during her work and travels.

“It’s a garden that has beautiful flowers, but it’s really about the stage and the structure and the experience,” Symmes says. “What’s great is you can wander through that garden and you are drawn down the steps and through the garden ‘rooms’ but you don’t really break a sweat. You can walk all the way down to the bottom and all the way back up and feel comfortable, because it’s so beautifully designed in terms of places to rest and stop. It’s almost like a choreography through the garden that allows you to just get lost in it and not even be aware of the incredible slope.”

It offers a delightful contrast to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden. Created between 1926 and 1930 by Farrand and its namesake, the garden is set amid acres of moss-carpeted woods. The “Spirit Path” on the west side of the garden invites visitors to stroll past six pairs of Korean tomb figures. These pieces, along with other Asian sculptures from Japan, China and Korea, are integral components of the garden. They are thoughtfully placed to evoke a contemplative quality.

“At the end you come to a gate and then there is this most breathtaking, drop-dead flower garden you’ve ever seen,” Symmes says. Among the 600 plants on Farrand’s design list were delphiniums, foxgloves, hollyhock and lilies, along with thousands of annuals that make the garden still explode in color. “The scale of it is so enormous that it’s hard to

fathom,” Symmes adds.

“I think she was always trying to draw you from one part of the garden into the next. There was a progression from the built landscape into nature. Her ultimate idea was to get people out of the house and into nature. Her gardens were designed to have these beautiful formal spaces near the house and then you would see something that would draw you and make you want to continue on and ultimately find yourself in the wild landscapes and closer to nature.”

“Beatrix Farrand’s American Landscapes” will be shown across the country and locally at an upcoming symposium on Farrand hosted by the Beatrix Farrand Garden Association at Bellefield at Historic Hyde Park June 1 and 2. For more, visit beatrixfarrandgardenhydepark.org.