The grand estates that commanded the Hudson in the late 19th century might conjure the names of Astor, Gould, Morgan and Rockefeller but not that of Caesar.

And yet, it was one of the original Caesars — the Emperor Claudius, great-great grandnephew of Julius Caesar — who was linked to Greystone Castle, once the Tarrytown home of Josiah W. Macy Jr., a partner of John D. Rockefeller’s in Standard Oil.

How Claudius — popularized in the Robert Graves’ novel “I, Claudius” and the addictive 1976 BBC series — came to be associated with Tarrytown is a story steeped in history, his and ours. And it begins — or rather the ending does — with Greystone on Hudson, a more than 100-acre luxury residential development on the site of the former estate.

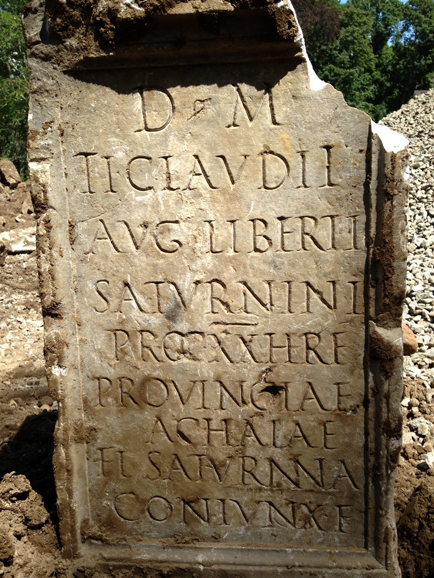

It was in the summer of 2015 that Andy Todd, president of Greystone on Hudson, and his team discovered a marble artifact with a Latin inscription while excavating for one of the homes, which they are now building. They did what any modern person would do — Googled the Latin inscription. Ultimately, their detective work led to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which authenticated the find as the funerary pillar of Tiberius Claudius Saturninus, a former slave who collected inheritance taxes for the Emperor Claudius in Greece. (Employing freed slaves in Rome’s civil service was the kind of compassionate innovation that helped earn Claudius, whose physical infirmities belied a shrewd mind and a scholarly temperament, a reputation as one of the more judicious Caesars. That and the fact that he was bookended by two mad emperors — his nephew Caligula and his grandnephew and stepson, Nero.)

Today, this funerary cippus is ensconced in The Met’s Leon Levy and Shelby White Court in the Greek and Roman galleries. Even if you know no Latin, you can make out the names of the deceased, his wife and his region, Achaea (Greece). The pillar is not merely a tombstone but a onetime reliquary, damaged on top where it was hollowed out to contain Saturninus’ ashes. (The lid that would’ve sealed the ashes in place is missing.) Decorated with a relief of a pitcher on the left side and a disk or dish on the right, the cippus is an indication of the Roman respect for death. Not only would citizens, or freedmen like Saturninus, be given such a burial but slaves as well.

But how did a Claudian artifact wind up in Tarrytown? In 1893, Josiah Macy’s widow, the former Caroline Louisa Everit, purchased it at auction at Rome’s Villa Borghese. In time, however, Greystone Castle and its treasures went the way of many of the great Hudson River estates. In the first half of the 20th century, Todd says, it was a home to a dance school led by Elizabeth Duncan, sister of modern dance diva Isadora Duncan, and, later, the militaristic Tarrytown School established by publisher and fitness enthusiast Bernarr Macfadden. In 1976, Greystone Castle burned to the ground and the Claudian link was buried with the past.

Until now. Driving through the serpentine Greystone on Hudson, you get the sense that Claudius and his backstabbing, power-grabbing family would have been as content there as they were in their villas in Capri. Each of the planned houses — there will be 20 in total by 2020 — is individual in character and set apart from the others, with unique riparian views. At Greystone on Hudson, you have neighbors, but you’d never know it.

We begin our tour at the entry where the castle’s original wrought-iron gate, crowned by a “G,” offers a stately welcome, as does the gaslit sentry house made of white wood and Manhattan schist. Indeed, all along the soaring Carriage Trail — named for the horse-drawn carriages that would wind their way up to the castle — you’ll find stone walls. (The stone is quarried on the property and cut by 14 masons for use mainly in the construction of the houses.)

Sugar maples also line Carriage Trail. They are among the mature specimen trees — including beeches, oaks and sycamores — gracing a landscape that beguiled Todd.

“We were looking for land to buy and build on (in 2012) when we saw this,” Todd recalls. “We looked at it and said, ‘Wow, this is such a beautiful parcel of land and only 13 miles from New York City.”’

Todd takes us to a ravine that cascades down to a pond the color of Roman glass. Three parcels share the ravine and pond, Todd says, and the entire site backs up onto Taxter Ridge Park Preserve in Greenburgh, perfect for cross-country skiing and hiking.

But you don’t have to be athletic or outdoorsy to enjoy Greystone. The versatility of the development is evident in the first two houses, both occupied. The first is an imposing stone, turreted affair, perched on a height; the other, a warm, woodsy Dutch Colonial with a generous wraparound porch.

The third — the roughly 22,000-square-foot, $12.9 million abode under construction on the site of the original castle and the Claudian discovery — is designed as an entertainment paradise, with an outdoor pool and tennis court, an indoor basketball court, a 14-seat theater, a wine cellar and a two-story Tudor-style library trimmed in mahogany that would surely have enticed the studious Claudius.

The copper-trimmed stone house, embellished with Palladian windows, corbels and gables, also contains 12 en suite bedrooms, and a 4,000-square-foot attic that leads to a rooftop deck, or widow’s walk (so-called for the rooftop vigil mariners’ wives kept for their husbands, often in vain).

The houses — which range from 8,000 to 25,000 square feet and $4 million to $20 million— will all feature geothermal heating. (This would no doubt have pleased the ancient Romans, who knew a thing or two about engineering.)

But then, Todd says, Greystone is about marrying the present to the past.

“Everything we’re doing is to create an Old World feel. We found the tombstone, which goes with the history of how people lived in (the 19th century). It’s part of what makes this place really special.”

For more, visit greystone-on-hudson.com.