Some people eat to live. But for the fortunate who live to eat, Chinese cuisine can be an adventure into a world of new flavors and delights. Chinese cookery, as a distinctive and unique culinary art, has been developed over the centuries as an extension of Chinese culture. Cooking is learned not only from studying a recipe but from attention to theory, by practice and care. In China, eating is a prime source of enjoyment and celebration. Good cuisine is considered a measure of civilization. Although chefs of great skill are prized throughout the world, nowhere is the Tai See Foo (chief chef) held in such importance as in China.

Every country and region has its own national or favorite food. China is divided into distinct schools of cooking – each distinguished by a variety of spices and sauces. The four most important are Beijing, Canton, Shanghai and Sichuan. By the time of Confucius in the late Zhou dynasty (770-256 B.C.), gastronomy had become a high art. The philosophy behind it was rooted in the “I Ching” and Chinese traditional medicine. Food was judged on color, aroma, taste and texture. A good meal was expected to balance the Four Natures (hot, warm, cool and cold) and the Five Tastes (pungent, sweet, sour, bitter and salty). The use of chopsticks as eating tools necessitated that most food be prepared in bite-size pieces.

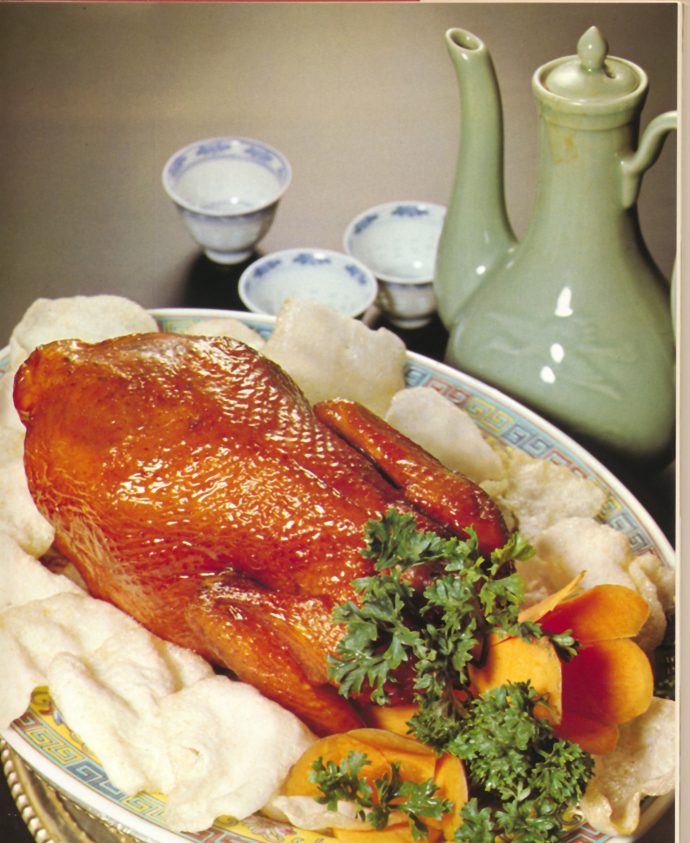

In later years, old Peking, now Beijing, became for Chinese food what Paris is for French food – the representative of a nation’s cuisine. There are hundreds of traditional Chinese dishes from different regional cuisines, but Peking Duck is feted as the national dish, especially in China’s capital. Unlike hamburgers or hot dogs in America, Peking Duck is not an ordinary everyday staple. Roasted Peking Duck (see recipe) first appeared during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) but because of the huge expense and complexity of the preparation, it was limited to the imperial court menus. Poets and writers penned flowery odes to the dish while commoners drooled at this unobtainable food of the gods. For centuries this imperial fowl, unlike the traditional American Thanksgiving turkey, was the exclusive preserve of emperors, aristocrats and wealthy elite to be served only on special occasions.

Now Peking Duck exists for the masses, but it is not cheap and thus is still considered a gourmet delicacy. Most tourists in Beijing make a beeline for the famous Quanjude, one of Beijing’s oldest restaurants specializing in duck. In the mid-1800s, its founder bribed a retired imperial chef for his coveted roast duck recipe and opened a street café to serve the renowned delicacy to eager, upwardly mobile, status-conscious diners. Quanjude expanded rapidly. The restaurant grew into a massive flagship, with seven noisy floors. But in the process the restaurant lost its appeal for those of us who prefer a finer ambience.

When I lived in China, before the Communists arrived in 1949 and during many recent visits as a journalist, my Chinese friends readily gave me advice concerning various food energies, called qi, which could be interpreted as food power. According to Alex Tan, a practitioner at the Straight Bamboo Chinese Medicine clinic in Beijing, there’s a big difference between how people in the West and people in the East describe food.

“Typically in the West,” Tan says, “they take a food, isolate it and break it down into component parts, such as fats, carbohydrates and calories. That food, tested in any laboratory in the world, would get the same exact results. In China, however, we look at a carrot, then eat a ton of carrots, and we describe what it does to us. It’s observation-based science.”

Dietary therapy, along with massage, herbal medicine, acupuncture and gigong exercise, are the five main pillars of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). According to TCM theory, you can benefit by eating food containing seasonal energies. In China there are five, not four, seasons – spring, summer, late summer, autumn and winter, and each season corresponds to an element, an organ, a taste, a weather attribute and a process.

Sofia Du, a chef and nutritionist in Beijing, says, “Our bodies are designed to eat with the season. These foods are more beneficial, because they live in the same climate as you, and therefore, meet your body’s needs. So, even if I like passion fruit, for example, it’s not good for me because it is grown in the south and I am a northerner.”

In summer, one is advised to stay refreshed by eating more “cold” foods like melons, persimmons, pears and cucumbers. Most Chinese foods, especially dumplings, can be prepared in an infinite number of ways, but most recipes are rooted in theoretic dietary principles. In the cold winter months, foods “warm” in nature, such as red meat and ginger root, can help the body combat the chill. It’s also the time for banquets and parties. Ice cold beer and all alcohol is considered “hot” because it heats us up internally.

Banquets are traditionally served on a round table with a large lazy Susan in the middle laden with a variety of appetizers. You could leisurely pluck a bite-size portion of food with your serving chopsticks before gently passing it around on the lazy Susan. The last time we were in China, in 2012, we journeyed to Chongqing in Sichuan province to celebrate my husband Seymour Topping’s 90th birthday with old friends and our adopted Chinese son, Peter Ronning. It was in late December and Christmas carols blared continuously from a loud speaker. At the flower-bedecked table, we were amazed – then horrified – to discover that the lazy Susan had been mechanized. Shortly after we sat down, someone flicked a switch and the tantalizing dishes placed around it began twirling around at such a high speed that it was impossible to capture any food with our chopsticks before it whisked by us.

Chongqing is renowned for its delicious hot spicy foods and bold flavors, but we could only watch in mouth-watering frustration as the Sliced Hoisin Pork, Bean Curd, Spicy Chicken, Hot Turnips, smoked meats, spring rolls, seaweeds, chili peppers, ancient eggs, tree fungus, deep fried celery with red pepper, hot-pickled cabbage, Facing Heaven pepper and a variety of herbs sailed by. Our grandson Torin tried slowing it down by force so we could stab a portion but to no avail. Disaster prevailed. The peaceful meal turned into a race against the not-so lazy Susan and no one could find the remote. All decorum was thrown to the wind as it became a matter of survival. We all dived in. It was every man/woman/child for him or her self.

We licked the platters clean and ended up playing the traditional finger game – where the loser, not the winner, gets to drink the red or hot rice wine. No one worried about the mess we left on the table, because it was a considered a good sign that we had enjoyed ourselves.

Peking Roast Duck (Jing Ting Peking Ya)

Ingredients:

4- to 6-pound duck

2 tablespoons molasses

1 to 2 bunches scallions (white part only)

Hoisin sauce

Chinese pancakes

Preparation:

Mix molasses with 1 tablespoon water.

Wash duck well, remove fat from cavity and dip in boiling water for five minutes.

Hang duck in airy spot half a day. Rub with molasses mixture and hang again, overnight.

Cooking:

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Line a baking sheet with aluminum foil (optional). Place a rack over foil.

Place duck on rack and roast 90 minutes.

Raise oven temp to 425 and roast 15 to 20 minutes more.

Slit the scallion bulbs 2 inches down the stems, making a second 2-inch cut at right angles to the first cut.

Cover with ice-cold water until serving time.

To serve, slice off skin, cutting it into pieces 1-1/2 inches by 3 inches. Slice meat into bite-size pieces arranged with the skin.

Roll meat, sauce and scallions into Chinese pancakes, Chinese steamed bread or American bread.