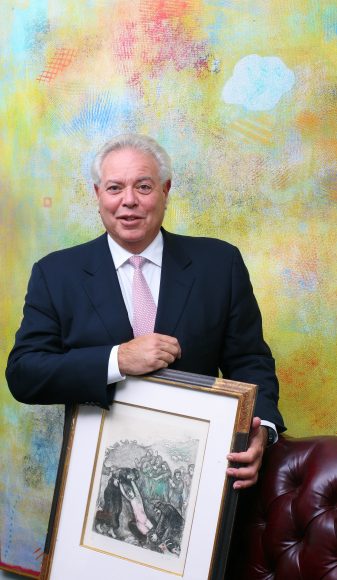

Joel S. Lever is an art lover like you or me.

“I buy art the way most people do – to fit over the couch or because it has great colors or because it makes me feel good.”

One wall of his White Plains office is lined with biblical prints by Marc Chagall – hand-colored by the artist. Across from his desk is a bright yellow floor-to-ceiling painting by the Abstract Expressionist Robert Natkin. Lever points to the various faces you can find in the work with such enthusiasm that you would swear he’s a curator.

But he’s an attorney, a founding partner in the firm of Kurzman Eisenberg Corbin & Lever LLP, one whose specialties include art law. And as an art attorney, he knows that a painting or sculpture is about more than how it is displayed in the home or how it makes you feel.

Art, he says, is an asset class, just like a house or a car – only more complicated in part because high-end art is not highly regulated.

Lever got into the field 30 years ago when he represented a multinational corporation whose assets included artworks. Since then, he’s represented brokers, dealers and collectors who leverage their multimillion-dollar collections to buy more art in what is today a hot market, particularly for Impressionist and contemporary works. It turns out that banks are willing to lend money to big-time collectors – any art worth less than $50,000, forget about it, Lever says – although don’t look for the bank to fork over the collection’s entire value. If your collection is appraised at $50 million – and you’ll be paying for that appraisal to satisfy the bank – you’ll get 25 to 50 percent of the collection’s “loan to value.” So $12.5 million to $25 million – a nice chunk of change for you to spend on that Damien Hirst you had your eye on.

Most high-end collectors have established relationships with dealers, galleries and auction houses. But even the savviest collector can be what Lever calls an “emotional buyer,” because art is subjective.

Remain cool-headed, however, “and make sure you know who owns (the work),” Lever says.

This can be easier said than done, because buying art is not like buying a car or a house, he adds. Cars and houses have titles. Artworks have titles, too, and provenances – histories of ownership that can contain gaps, particularly when works are stolen as in the case of Nazi-looted art.

“There’s a saying,” Lever adds. “‘You can’t get title from a thief.’”

He points to a recent case in which a client purchased a work at an American art fair. (About 40 percent of the roughly $66 billion in annual gallery art sales are made at art fairs like Basel in Miami or in London, Switzerland and Hong Kong.)

No sooner did Lever’s client have the $500,000 painting in his possession than he received a letter from The Art Loss Register, created by The International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR), stating that the work had been stolen and demanding its return. It turns out it had been consigned some 10 years earlier to a gallery. The gallery owner sold it and took the money and ran to South America. The original owner of the painting was ultimately paid off by the insurance company. Now the insurer, through the registry, was looking either for the artwork or it monetary value. Needless to say, the provenance of this painting was far from exact.

Lever argued “voidable title.” The original owner, having placed the work into commerce, had no more claim on it. Lever also went after the German gallery that had sold the work to his client at the art fair. That gallery argued that the U.S. had no jurisdiction over a foreign gallery. But Lever countered that the gallery was operating under the rules established by the American art fair and U.S. laws of jurisdiction. After seven months the issue was resolved out of court and his client’s title to the work was confirmed.

Sometimes the perils of art ownership lie inside the home. That’s what one client found out when his $10 million painting – carefully hung and watched over by a security camera – fell off the wall, incurring a tiny hole. (Hey, stuff happens. Las Vegas casino impresario Steve Wynn was all set to part with “Le Rêve” (“The Dream”), a painting of Pablo Picasso’s mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, to Steven A. Cohen, founding chairman of Stamford-based SAC Capital, for $139 million in 2006 when he accidentally elbowed it, putting a silver dollar-size hole in the canvas and ending the deal. Was it an emotional farewell or Freudian slip of that elbow? Seven years later, Wynn sold the restored painting at a Christie’s auction to Cohen for $155 million – or an extra $16 million.)

Back to Lever’s client. Lever put together a crisis management team that included an insurance expert, a restorer and an appraiser. The insurance offer came in at $100,000. Lever was able to get his client $1 million. Actual cost of the restoration – $3,500. (Recounting of this story, Lever says – priceless.)

Such clients are deliberate investors or collectors. Then there are the accidental investors or collectors, who may inherit an artwork like the one another client bought for $25 and kept in his basement. When he died, his heirs had it appraised.

It was worth about $500,000.

Here it gets tricky, Lever says, because the accidental collector/investor may not be familiar with the for-profit world of auction houses and the fees and taxes they’ll have to pay on selling a work.

What can you do?

One choice: You can leave it to Lever.