Diamonds may be a girl’s best friend, but not even they can outshine the ruby.

“The last 70 years have seen the clever and persuasive marketing of diamonds,” gemologist Joanna Hardy writes in her new book “Ruby: The King of Gems” (Thames & Hudson, $125, 320 pages). “Yet rubies are far rarer than white diamonds, a fact that is being recognized in the world-record-breaking prices they set at auction.”

Photography by Nick Welsh.

If the worthy woman of Proverbs is a “price far above rubies,” her modern counterpart knows a ruby’s value. Rubies have been worn by bellwethers from Elizabeth I to Elizabeth II to Elizabeth Taylor. No wallflowers they, nor were Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Audrey Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich, Princess Grace, the Duchess of Windsor and Princess Margaret, to name but a few who loved their rubies center stage with diamonds as the supporting player. (Take that, diamonds.)

“Maybe it is subconscious, but there seems to be a common belief that rubies are not for the faint-hearted,” Hardy writes. “Women with attitude and strength, who ooze passion and are wildly independent have chosen to wear rubies or have been given ruby-set jewels by their admirers.”

History shows, however, that red gemstones have not been the province of the female sex alone. The great English warrior-king Henry V reportedly wore the 170-carat Black Prince’s Ruby — named for his great-uncle Edward, son of Edward III — into the Battle of Agincourt where it saved his life. (The gem was affixed to Harry’s helmet, staving off a blow from the Duke of Alençon’s ax.) Today the hen’s egg-sized stone commands pride of place on the Imperial State Crown, which resides in the Tower of London. (The queen wears it for the opening of Parliament.)

But is the Black Prince’s ruby real? Hardy describes it as an “ancient ruby,” because until the 18th century, jewelers were unable to differentiate among minerals. Today we know that what we thought were rubies, which are made of aluminum oxide, may really have been spinels, which are made of magnesium aluminum oxide. (Both contain trace impurities, including chromium, which give them their color.)

The two stones refract light differently, too, so that the spinel shows the same color from all angles, while the ruby alternates orangey-red and pinkish-red.

Another difference, Hardy notes, is that while spinels can be purple, green or blue as well as pink and red, rubies are only some shade of red. (If a “ruby” is any other color, it is a sapphire, “but that is another story,” Hardy writes.)

This differentiation should not devalue the spinel — brought to the West along with other gemstones from Asia along the Silk Road — in the eye of the contemporary collector, she stresses.

“Today, spinels are increasingly sought after for their beauty, durability and rarity, all qualities that are highly valued by stone connoisseurs and jewelers.”

Indeed, part of what makes Hardy’s crimson coffee-table book so refreshing is her egalitarian approach to jewels. For her, “semi-precious” is a misnomer. “…All gemstones are precious so long as they display beauty, rarity and durability.”

As for the notion that a ruby should be only a certain color, she observes: “A colored gemstone should be chosen because it ‘speaks to you,’ not because it has been described in a particular way, such as ‘pigeon’s blood’ in the case of a ruby.”

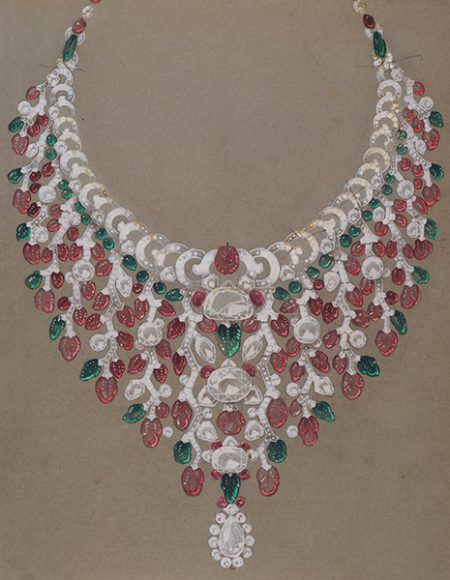

commissioned by Mrs. Ronald Tree, later Mrs. C. G. Lancaster, in 1930.

© Cartier, courtesy of the Cartier Collection

Photography by Nick Welsh.

A few quibbles about captions: Princess Grace — seen in an official 1959 portrait wearing a Cartier ruby and diamond diadem and diamond necklace and in a ruby and diamond tiara and necklace at Versailles in 1973 — was a Serene Highness, not a Royal Highness.

And the caption for a late-16th century portrait of Henry V, which shows him wearing several red gemstones, describes him incorrectly as the Black Prince.

We should also note that while the book dwells at length on Myanmar (the former Burma), from which many of the finest rubies come, and the political turmoil that led the United States to ban the importation of Burmese rubies for a time, its publication preceded the current crisis in which some 600,000 Muslim Rohingya have fled persecution in Buddhist Myanmar to neighboring Bangladesh.

Still, Hardy’s interdisciplinary approach — spanning art, science and history — and the stunning illustrations make this a gem — no, a ruby — of a book.

For more, visit thamesandhudsonusa.com.