Georges Seurat, the late-19th century French painter, is best-known for two things — his Pointillist or dot technique and its ultimate expression, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.”

That 1884-86 oil on canvas, which hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago, and its creator’s brief life are the subject of the 1984 Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine musical, “Sunday in the Park With George,” now an acclaimed Broadway revival starring Jake Gyllenhaal.

But Seurat’s “Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque)” (1888) “is the most haunting and enigmatic painting of this major artist’s short career,” writes Richard Thomson, author of the catalog accompanying “Seurat’s Circus Sideshow,” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan through May 29. It was, as the introductory text panel explains, the first of six important figure paintings by the artist to portray popular urban entertainment in a nighttime setting. In showcasing this jewel from its collection, The Met — which staged a spectacular Seurat retrospective in 1992 — has created a thoughtful exhibit that not only honors Seurat but captures the gritty endurance of the circus at a time in our culture when its traditions have been transformed.

The son of a wealthy speculator, Seurat was born in Paris where he studied at the École Municipale de Sculpture et Dessin near the family home and then at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts. All his life, he would be a study in contrasts himself, at once passionate and precise, a seeming paradox that would feed and would in turn be fed by his training and subsequent work. The Met show includes Charles Simon Pradier’s “Tu Marcellus Eris,” an 1832 neoclassical etching and engraving after that master of line and chiaroscuro, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, whom Seurat copied.

But he was also drawn to the dynamic palette of Eugène Delacroix’s dramatic canvases. Line and color would come together in a subject that fascinated Seurat and the other French painters of the 19th- century’s close — Parisian playtime, which included thronging to the circus.

Seurat captured the center ring in his 1891 work “The Circus,” in which a bareback rider, balancing on one foot, comes perilously close to falling off, her flying red hair flaming atop her head. The surrounding ringmaster, tumblers, musicians and spectators are rendered in primary colors — red, blue and yellow — that meld and yet remain distinct.

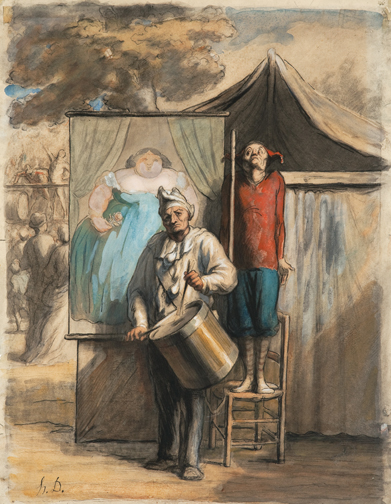

He was, of course, not the first to depict what would become known as “the greatest show on earth.” The Met exhibit includes several 1865-66 drawings by the caricaturist Honoré Daumier, whom the later generation admired for his antibourgeois sentiments. One of these mixed media drawings, “Saltimbanques” — from the Italian for circus performers, saltimbanco, meaning “one who jumps on a bench” — offers a brilliant distillation of circus life in four figures. As the father, in clown attire, focuses on beating a drum to attract a distant crowd at another event, the older son puffs out his chest, the mother hangs her head in despair and the younger son plays in the dirt, oblivious to the family’s desperation. Anyone who has ever tried to sell something — indeed anyone with a shred of compassion and insight — will recognize Daumier’s exploration of four attitudes toward the human condition.

“Circus Sideshow” — an exhibit you can practically smell — does a wonderful job of crystallizing the perseverance of the late 19th-century circus performer amid an atmosphere that was at times tawdry, usually raucous and downright exhausting.

For spectators, however, it was catnip. They, like Seurat, thronged to the Cirque Corvi, which played Paris as part of the annual post-Easter Gingerbread Fair, featuring the delectable pain d’épice in assorted fantastical forms that included real and imaginary gingerbread animals. The fair was staged at the former Barrière du Trône, where Louis XIV and his queen, Maria Theresa of Spain, entered the city in 1660 as newlyweds. In Seurat’s day, it had been redesigned as the place de la Nation, a circular hub from which radiated roads and boulevards to mirror the more upscale Place de l’Etoile to the west.

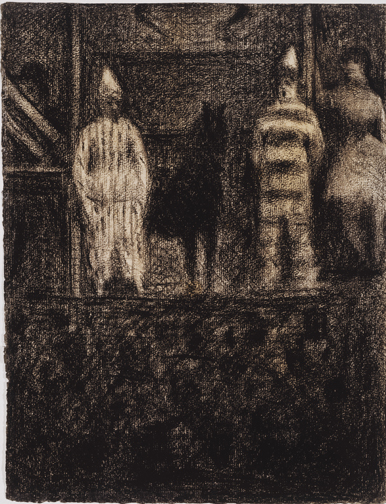

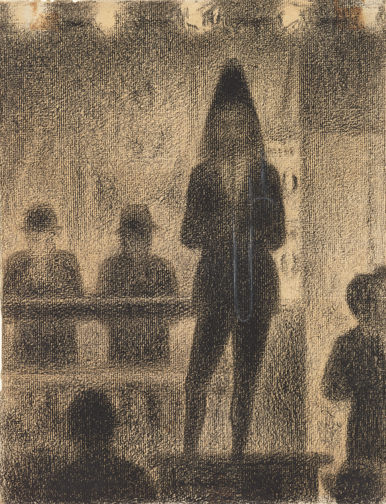

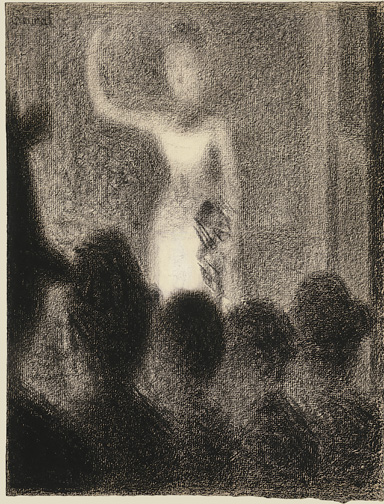

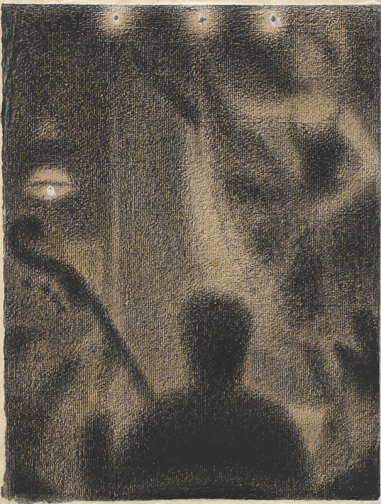

People from all walks of life crowded the fair and the circus. But Seurat chose to focus instead on a group of sideshow, or parade, musicians, particularly a trombonist, who helped reel in the audiences. In the spring of 1887, he created a number of Conté crayon drawings, using his Pointillist technique. For the painting, he also drew on Divisionism, or chromoluminarism, in which colors remain distinct so that the eye “mixes” them optically. A yellow circle might surround a green one. A red dot might be juxtaposed with a blue one. But you only notice this up close, along with a purplish blue border of dots that serves as an inner frame.

What you see when you step back is a trombonist in a traditional conical hat and leggings performing on a stand while bowler-hatted brass and wind players back him up to the left. A gentleman at right takes it all in as another man, hands on his lapels, looks up at him. The painting is bordered by gaslights atop, a skeletal tree to the left, a group of chatting spectators at bottom and another group climbing the stairs to the box office at right. The marriage of sharply drawn figures and shimmering color creates an effect at once of heightened reality and heightened unreality.

“Circus Sideshow” was exhibited at the fourth Salon des Indépendants in 1888, sold from the artist’s estate in 1900 — years after his death at age 31 of undetermined causes — and became part of the first exhibit at The Museum of Modern Art in 1929. Three years later, it was purchased by Singer Sewing Machine Co. heir Stephen C. Clark, older brother of Clark Art Institute co-founder Sterling.

In 1960, Stephen Clark bequeathed “Circus Sideshow” to The Met, where it continues to haunt.

“The overall effect of the painting is at once subtle and ambiguous,” Thomson writes, “on the one hand warm and indistinct, on the other ordered and hieratic. For out of the ordinariness of his fellow citizens at a fairground Seurat conjured a night scene of exquisitely measured mystery.”

For more, visit metmuseum.org.