“I’ve walked this earth for 30 years and, out of gratitude, want to leave some souvenir.”

— Vincent van Gogh, August, 1883

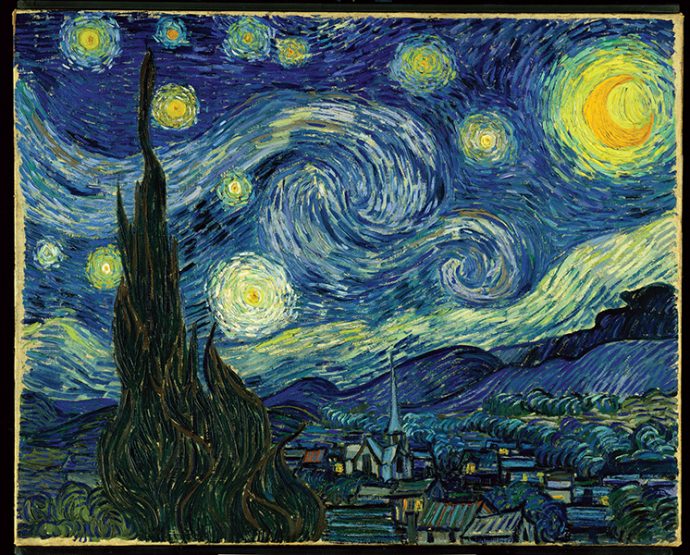

It’s a ritual as regular as the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace. A group of admirers gathers before a painting that is the sole occupant of a partition on the fifth floor of The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. They stand in a makeshift semicircle a few feet away, under the watchful eye of a museum guard to their left, raise their cell phones and start recording a virtual experience. The guard looks at us, observing nearby, and rolls his eyes as if to say, “They could be looking at the painting instead.”

After a while, these fans drift away and a new group forms to take their place. Some turn around to try to take selfies with the picture, difficult given the throng. Occasionally, however, one breaks free from the pack to step back and merely stand still and silent, communing with the painting itself.

“It has a lot of flow to it,” Rebecca Chapin, a programmer from Washington, D.C., says, a “a kind of serenity. But then, I’ve always been someone who loved the night.”

Vincent van Gogh (1853-90) was also “in love with night,” as Shakespeare might’ve put it, but also with any time of day that cast a trajectory of shifting light across the landscape of his beloved nature. After the pre-Christmas breakdown that spurred the infamous self-mutilation of his left ear, the artist committed himself in the spring of 1889 to the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. It was there — where he would create some of his greatest works — that he captured a view of the village just before sunrise that he deemed a failure but that Chapin and its many other admirers worldwide know as “The Starry Night.”

The work is an idealized view from that room. For one thing, Van Gogh wasn’t allowed to paint in his second-floor cell — only sketch in charcoal and ink. Asylum officials gave him another room on the ground floor that served as his studio. For another, artists are always conflating experiences to conform to their imaginations, so while the “Morning Star” (Venus), which appears to the right of the cypresses on the canvas, would indeed have been present in the Provençal sky at that time, the moon, on the far right, was actually a waning gibbous and not the waning crescent Van Gogh depicted. Nor could he see from his room the sleepy village he created of ultramarine and cobalt blue oils, dwarfed by those weirdly radiating stars of zinc and Indian yellow.

What to make of those orbs — shimmering in the mistral and changing light — that leave us starstruck? At the time, Van Gogh was torn between painting from nature, as he always did, and painting more from imagination as advocated by friends and colleagues Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard. The son of a minister and himself a failed minister who became disillusioned by organized religion, Van Gogh nonetheless saw something mystical in the stars, which for him carried a sense of hope and the promise of an afterlife.

Nevertheless, with “The Starry Night,” he felt he had overreached, as he wrote in one of his many impassioned letters to his brother Theo, an art dealer in Paris who served as his patron, soul mate and lifeline: “…once again I allowed myself to be led astray into reaching for stars that are too big — another failure — and I have had my fill of that.”

When it came time to send Theo a batch of new paintings, “The Starry Night” was not among them — at first. But in the fall of 1889, Van Gogh sent the painting to his brother. Within two years, they would both be dead and it passed — as did so many of the works and the letters — to Theo’s widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, the mostly unsung heroine of the Van Gogh story. If her husband had, in a sense, made Van Gogh the artist possible, she would make Van Gogh a legend.

“The Starry Night” would pass back and forth from her to a number of acquaintances and the Oldenzeel Gallery in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, where it wound up in the 30-year stewardship of one of the city’s most prominent residents, Georgette Petronelle van Stolk. She sold it to Paul Rosenberg and through him it came in 1941 to MoMA, where it has been ever since — helping to illumine a city that is itself in thrall to the night.

And firing the imaginations of others. “The Starry Night” has figured in everything from “Doctor Who” to “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” “The Simpsons,” Akira Kurosawa’s “Dreams” and “The Great Debate: The Storytelling of Science,” in which astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson plumbs the painting as a narrative of the night sky.

But two works inspired by “The Starry Night” have a strong connection to WAG Country. One is by Neil Waldman, the painter and illustrator who teaches watercolors at Westchester Community College’s Center for the Arts. His children’s book “The Starry Night” (Boyds Mills Press, 1999), based on a fantasy from his own Bronx childhood, tells the story of a little boy who meets Van Gogh painting in Central Park and then accompanies him around Manhattan, which he begins to see through the artist’s Impressionistic eyes. They wind up in front of “The Starry Night” at MoMA, where Van Gogh vanishes but not before inspiring the boy to paint. (The book’s final page and endpapers feature drawings of “The Starry Night” by children in the art class Waldman taught for the Southern Westchester Board of Cooperative Educational Services.)

The other work is the song “Vincent” by New Rochelle native Don McLean, each stanza of which begins with the words “Starry, starry night” and which uses the swirling textures of the artist’s canvases and the sadness of his brief life as poignant, poetic metaphors for the gulf between artist and audience and the ultimate inscrutability of art.

Back at the museum, the guard warns an admirer against getting too close to “The Starry Night.” An alarm will sound. And perhaps that, too, is a metaphor. Stand back too far, clicking away, and you risk disconnecting from the actual moment.

But stand too close and you risk missing the big picture — the starry souvenir of the artist’s self.

For more, visit moma.org.