Perhaps the most ruthless “power trip” in the world began with a son’s mission to avenge his father. The great Mongol warrior who ruthlessly carved out the largest empire in the world, before the British Empire, was known by many names. As a child he was Temujin. As Mongol chief, he was known as “The Scourge of God.” But the name that went down in history was Genghis Khan, meaning “Universal Ruler.”

Temujin was born in central Mongolia around 1162, when Mongolia was a state of fierce warring tribes. He was born with a blood clot on the palm of his right hand, a sign in Mongol folklore that he was destined to become a great leader.

When he was 9, his father, Yesukhei, took him to live with the family of his future bride, Börte. On his way home, Yesukhei encountered members of a rival Tartar tribe. They invited him to a conciliatory meal, but he was betrayed and poisoned. Temujin swore revenge and returned home to claim his position as clan chief. His mother, Hoelun, taught him the grim and brutal reality of living in a turbulent Mongol tribal society and the need for alliances and he began his ascent to power. By the age of 20, he had organized an army of 20,000 warriors and set out to unite all the Mongol tribes under his rule.

Through a combination of outstanding military tactics and merciless brutality, Temujin avenged his father’s murder by decimating the Tartar army and killing every male Tartar over 3 feet tall. He went on to defeat his main rival, the Taichi’ut tribe and in a show of cruelty that defined his tactics, he had all the chieftains boiled alive. By 1206, Temujin had enlarged his army to 80,000, defeating and uniting all the tribes of Mongolia into an army of fierce mounted warriors. After the victories, the rival tribes agreed to peace and bestowed on Temujin the title of Genghis Khan, which carried both political and spiritual significances. The leading shaman declared Genghis Khan the representative of Mongke Koko Tengri (the “Eternal Blue Sky”), the supreme god of the Mongols. With this declaration of divine status came the understanding that Genghis Khan was destined to rule the world. It was with this religious fervor that he told his enemies: “I am the flail of God. If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.” At the age of 44, he set forth with his Mongol soldiers to fulfill his destiny.

The warriors, mounted on sturdy Mongolian ponies, had one great advantage. They had invented the most powerful weapon in the world at that time – the iron stirrup. This enabled the cavalry members to stand up in their saddles, maneuvering their galloping horses with their legs while using their hands to launch their spears and shoot arrows straight. Their military tactics were also superior. The fighters coordinated their advance with a signaling system of burning torches and smoke. Flags signaled further orders and huge drums sounded the signal to charge. The soldiers were equipped with bows and arrows, shields, daggers and lassos. They carried large saddlebags, which could be inflated as life preservers to cross rivers and also used to carry food, tools and clothing. Cavalrymen also carried small swords, javelins, body armor, battle-axes and lances with hooks to pull enemies off their horses.

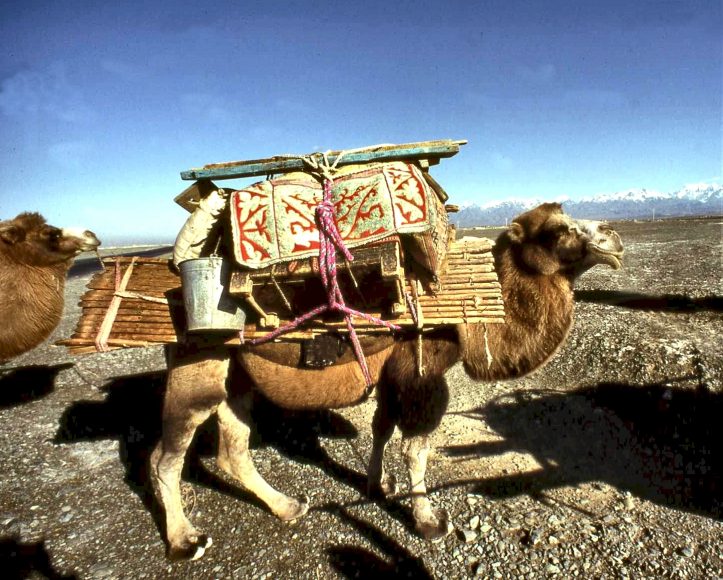

The Mongols thundered through Central Asia along the Silk Road on a mission of conquest, rape and pillage. Whole populations were systematically wiped out. Rivers were diverted; irrigation channels cut off, people starved, cities burned and dams were smashed open to flood the remains. No mercy, no prisoners. Migrations of whole populations began and continued for centuries.

The conquest devastated North China and Central Asia. Any city along the Old Silk Road, Buddhist or Muslim, that refused to join his armies or pay due respect was obliterated. When the lost cities were discovered by foreign archeologists some 800 years later, they told of a desert strewn with so many human bones that the travelers piled them up as trail markers.

The Mongol Empire, which stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Japan, lasted well after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227. One of his grandsons, Kublai Khan, conquered China, establishing the Yuan Dynasty and entertaining explorer Marco Polo.

By the time Polo left China in 1291, and returned to Venice to tell his fantastic stories about his 16 years in the fabulous court of Kublai Khan, most of the Buddhist cities, with all their gold encrusted temples, monasteries, works of art, sacred scriptures and invaluable manuscripts with forgotten secrets had vanished beneath the shifting sands dunes of the deadly Gobi and the Taklamakan (The Desert of No Return.)

But in the end, who was the conqueror and who the conquered? Over the two centuries of Mongol rule, the Mongolians were assimilated into Chinese culture. Kublai Khan was converted to Yellow Hat, Tibetan Buddhism. His armies became decadent and lost their will to fight. They were driven out of China by the Chinese, who established the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Thus ended the world’s longest power trip.

The Mongols then retreated to what is today the independent Republic of Mongolia, formerly Outer Mongolia, and Inner Mongolia, still under Chinese rule. Both claim Genghis Khan as a national hero, although he is understandably despised in the Middle Eastern lands he decimated.

As for his exact cause of death, that remains a mystery. Some historians maintain he fell off a horse while on a hunt. But the report I like best is the one that claims Genghis Khan was castrated by a Tangut princess taken as war booty. She used a hidden knife to avenge his treatment of the Tanguts (Tibetans) and to stop him from raping her. Khan died from infection and she committed suicide by drowning in the Yellow River.

But not before she got, as it were, her pound of flesh.