The murder of George Floyd and subsequent protests have reignited the long-simmering debate over monuments to racist historical figures — thrown into sharp relief by the events of Charlottesville in 2017 when white nationalists marched on that Virginia city to denounce the removal of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s statue, killing three and injuring 34.

The question of Confederate statues — which were erected long after the Civil War in the era of Jim Crow segregation (1890s-1950s) and thus serve no purpose beyond intimidation — would seem to be a no-brainer. Losers do not get to dictate either the terms of their surrender or the trappings of their defeat. There are no statues to Adolf Hitler in Germany.

But what about the monuments to the victors, those flawed men — and yes there are almost always men, white men — who created, preserved and expanded this union, often at tremendous cost to others? Should their tributes be removed entirely, kept in place with contextual materials or moved to museums? Does it depend on the man and the monument? We can’t imagine the Washington Monument being dismantled, although much has been done in recent years to discuss President George Washington as a slaveholder, particularly at his estate in Mount Vernon, Virginia. Nor can we see the Lincoln Memorial being destroyed, although President Abraham Lincoln was slow to see blacks as intellectually equal to whites and was first and foremost interested in preserving the union, not freeing the slaves. That he did so and “gave the last full measure of devotion” with his life tilt the scale in his favor.

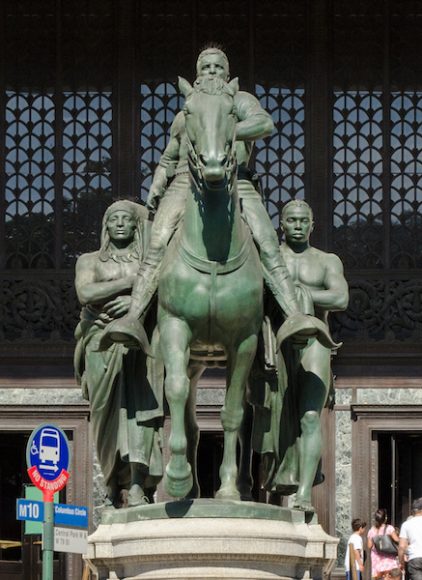

Other monuments, however, have come to their day of reckoning. New York City will remove James Earle Fraser’s 1939 equestrian statue of President Theodore Roosevelt, which stands in front of the American Museum of Natural History on city property on Central Park West. In making the request, museum president Ellen V. Futter said she offers no judgment of Roosevelt, only of the racially hierarchical composition of the statue, which shows him on horseback flanked by an African American and Native American on foot. (Futter’s statement may just be hair-splitting. It’s hard to separate the man — who espoused workers’ rights and imperialism, conservation and big game hunting — from the message.)

Opponents have said that by removing such statues, we are attempting to remove the past. You cannot, they say, read history — the story of the past — backward. True, but we live with the past, not in it as we try to learn from it. Many experts counter that what is needed is the curatorship to put these monuments in the context of their times. But even such scholarship may not be enough. In January 2019, the Museum of Natural History mounted an exhibit “Addressing the Statue” to consider myriad viewpoints on the Roosevelt monument.

It is one thing to study the past, however, another to celebrate it. The presence of such statues out of doors in places of prominence suggests an exaltation of the iconographies they espouse. The time for their removal has come.

Some of the statues will survive as museum exhibits; others as archival photographs; all as opportunities to understand where we’ve been and where we are going.

But there is something else we must understand: What is important or incendiary in one era is lost on another. In his poem “Ozymandias,” Percy Bysshe Shelley contemplates a statue of Ramesses II that lies in ruins. (Ever the iconoclast, Shelley discounted all the many sensuous sculptures of the pharaoh that remain throughout Egypt.)

Still, Shelley’s point is well-taken: The “immortality” conferred by stone and metal, like that of flesh, is fleeting indeed.