He created the alternating current induction motor, ensuring that the world could have continuous electricity.

He pioneered wireless technology — he is credited with inventing radio — prefiguring the digital revolution.

He dazzled the Gilded Age’s high society and hoi polloi alike, wielding light tubes, forerunners of fluorescence, like a 19th-century Jedi; unleashing a gnarled crescendo of AC voltage through his patented coil; and even taking hundreds of thousands of volts of electricity through his own skin.

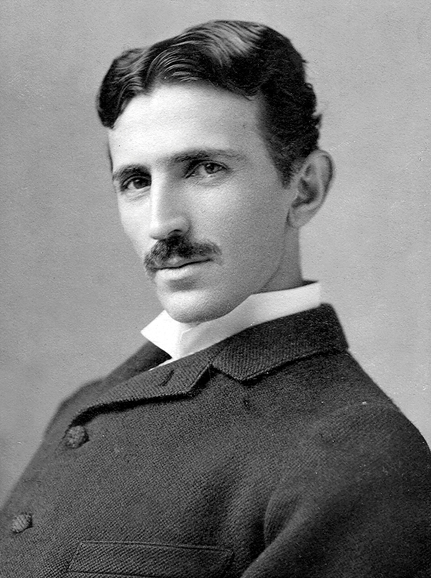

And yet when he died at the height of World War II, inventor Nikola Tesla was all but forgotten, a poignant figure, the ultimate eccentric genius, shuffling from one Manhattan hotel to another — always one step ahead of his creditors and always staying in a room and on a floor whose numbers were divisible by three; communing with pigeons in Bryant Park; subsisting on crackers somewhere between reality and madness.

But as Tesla would say, “Let the future tell the truth and evaluate each one according to his work and accomplishments. The present is theirs; the future, for which I have really worked, is mine.”

That future is now. In a time that has seen the likes of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, Tesla is the darling of Silicon Valley. His name is on everything from a unit of measure for the flux density of magnetic fields and an IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) award to airports, museums and, of course, the electric car company, while his complex persona has sparked movies (“The Prestige,” the forthcoming “The Current War”), novels (“The Invention of Everything Else”) and plays (“Tesla’s Letters”).

“When you think about electricity, you think of (Thomas Alva) Edison,” physicist Peter Fisher said in the recent “Tesla” documentary on PBS’ “American Experience.” “But Tesla was just more of an original American than Edison.”

That Tesla is still not thought of in the same breath as Edison or Guglielmo Marconi, who made the first transatlantic radio transmission, says as much about the vagaries of time, science’s knotty relationship to business and the shadow side of the American immigrant dream as it does about Tesla himself — a poetic, impractical man for whom capital, intellectual and financial, would be his making and his undoing.

Even now, he remains elusive, a man cast in myth who always seemed to be straddling two worlds — claimed by Europe (Croatia and Serbia) and America and, in America, by the East and the West. Fittingly he was born on the stroke of midnight July 10, 1856, in Smiljian, Croatia to parents who were ethnic Serbs, amid a raging storm. “He’ll be a child of the storm,” the midwife said. But his mother, an illiterate yet inventive woman, knew better. “No,” she said. “Of light.”

Tesla’s father was a Serbian Orthodox priest descended from a long line of priests who ingrained in his son the Orthodox belief that everything was ultimately knowable and expected him to join what was the family business. But possessed of an artistic imagination, his mother’s photographic memory, impressive linguistic skills and visions that he controlled with his mind, little Nikola devised a waterwheel as well as a windmill powered by June bugs. He even tried to fly off the roof of a barn. It was soon apparent that Tesla would never be a priest, and he ultimately made his way to the Austrian Polytechnic School where he would study math, physics and mechanics and where a pattern would emerge that would haunt him in America — a wealth of and an obsession with ideas, tireless work, money troubles, flame out.

Leaving school, Tesla bounced around Europe, taking low-level jobs where he could. But by then he was already fired up about alternating current. Direct current sends the flow of electrons in a loop, losing and limiting energy along the way. In alternating current, the electrons ebb and flow, sending electricity over long distances. But how to make it work?

For four years, Tesla thought of little else. He was like a young Bill Gates obsessing over software. And then one day in 1882 as Tesla was walking in a Budapest park with a friend, it came to him like a lightning bolt: Instead of having metal rub on metal, he devised a motor with an inner copper cylinder and sent electricity through the outer ring, creating a rotating magnetized device. No sparks, no smell, no breakdown — an elegant solution. Two years later on June 6, 1884, Tesla arrived in Manhattan with four cents, some favorite poems and a letter of introduction to Edison. But while Edison hired him immediately, he was invested in direct current and practical products he could sell. He wasn’t interested in Tesla’s AC motor.

After six months of fixing generators day and night, Tesla decided to go it alone. He was cheated out of patents for arc lights and dug ditches for $2 a day. Then he met George Westinghouse, the successful inventor of the railroad air brake, who in 1888 bought Tesla’s AC patents for tens of thousands of dollars. Now rich, Tesla would’ve been far richer still had he not relinquished the royalty of $2.50 per horsepower of AC sold to give Westinghouse more capital. To Tesla, wealth lay in ideas not cash.

The two would go on to electrify the Columbian Exposition of 1893 and harness Niagara Falls. Tall, dark, lithe and handsome in his cutaway and striped dress pants, Tesla would dine at Delmonico’s and the Waldorf Astoria, charming everyone from John Jacob Astor IV to Sarah Bernhardt to Mark Twain, despite his phobia for germs, pearl earrings and touching human hair. And though rumors percolated about his attraction to well-muscled young men, Tesla’s great love remained ideas.

This is where Tesla’s Gilded Age dream becomes tarnished. He dreamt of sending electricity and wireless messages around the world cheaply, even freely, burning through thousands of dollars of Astor’s and J.P. Morgan’s money respectively with experiments in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and on the 200 acres he called Wardenclyffe on Long Island. He produced patents but no products. And when Marconi sent the first transatlantic cable in 1902, Tesla’s fate was sealed.

For the rest of his life he longed to make enough money to return to Wardenclyffe, which he lost to his Waldorf debts. He died on Jan. 7, 1943, in Room 3327 on the 33rd floor of the New Yorker Hotel. Six months later, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Marconi’s wireless patents were really his.

But how many people know that today, despite Tesla’s popularity? W. Bernard Carlson, author of “Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age” (Princeton University Press, 2013) writes that Tesla’s relatively obscure legacy lay not only in his lack of a company of his own and tangible accomplishments but in his otherness — as a Serb and a possibly gay man in white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant America. (It’s interesting that although Tesla became an American citizen in 1891, the FBI ordered the Alien Property Custodian to seize his belongings, perhaps due to their possible international sensitivity, two days after he died. His effects were shipped to Belgrade, as well as his remains, in the 1950s.)

And yet, Carlson writes, that outlier status is part of the Tesla renaissance today.

Perhaps Tesla best understood that our successes and failures are two sides of the same coin, that human nature, like an invention, is all of a piece:

“Our virtues and our failings are inseparable, like force and matter. When they separate, man is no more.”