“When I find pleasure in orchids, I love uprightness; when I see pines and bamboos, I think of virtue; when I stand beside limpid brooks, I value honesty; when I see weeds, I despise dishonesty. This is what is meant by the proverb, ‘The Ancients get their ideas from objects.’”

– Emperor Ch’ien-lung, 18th century

Oriental gardens are a distinctive and empowering art form that originated 5,000 years ago in the unique gardens of China. The gardens of Japan, of bonsai, ikebana and miniature landscape art are intimately connected with the greatest of Chinese arts – landscape painting. In the 18th century, descriptions and paintings on scrolls, screens and porcelain were exported to the West and added impetus to the art of “natural” landscaping in England, while in the last century the flora of China transformed the work of gardeners all over Europe and America.

The love of flowers is an ancient passion among the Chinese. Today one cannot walk through a garden in England or North America without finding species of rhododendron, jasmine, azalea, lilacs, roses, clematis and tree peonies – which Marco Polo once described as “roses big as cabbages” – and countless other flowers that first appeared in China. Without Chinese gardens, we would not have garden chrysanthemums or peaches that came to Persia via the Silk Route across Asia. Perhaps the main difference between the theory and practice of garden design in the West and East is that in England and America a garden is planted, but in China a garden is built. A Chinese scholar’s garden is not attached to the house. His interests are in exotic architecture, space and layout as well as odd rocks, fairy-tale scenes and blossoming fruit trees. The buildings in Chinese gardens are reminders that gardens are meant to be lived in as well as viewed.

The early emperors of China contributed two major themes to the art of garden design – the vision of magical dwellings of the Eight Immortals and the idea of the park as a microcosm in which might be found all the riches of the world. Chinese gardens were not only the products of emperors. Rich men liked to show off their wealth by landscaping their estates. Later poets, painters, scholars and literary elites all added to garden design. In traditional China, the scholar-official stood at the pinnacle of society, second only to the imperial family. Following the ideals formulated by Confucius in the fifth century B.C., the officials retired early and lavished their resources on the cultivation of garden arts. After the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to 220), thousands of private gardens began to show the influence of changing values and to develop two different themes that were to become essential aspects of the Chinese garden. One concerns the expression of Taoist nature philosophy in gardens; the other the growth of a rich, unique and fascinating connection among the arts of gardening, painting, poetry and calligraphy.

Despite centuries of evolving garden design, the essence of Chinese gardens remains virtually unknown in the West, and even in the East, except for Japan and Korea, they have almost become a lost art. In The People’s Republic of China, many old and famous gardens that survived the wars and revolutions of the 20th century have now been restored and are open to the public. Part of their appeal is their strangeness. Everyone can feel visually empowered by the sight of a Chinese garden, but before their beauty and complexity becomes fully accessible to the viewer, it is necessary to understand something of the myths and meanings of the imaginary names that lie behind them.

In her book “A Chinese Garden,” Maggie Keswick makes an interesting comparison: “Perhaps the closest analogy to the experience these gardens offer would be a walk through Chartres Cathedral. In both, the first sensual impressions lead on to more cerebral pleasure and, lying behind the forms for those who wish to find them, are apparently unending layers of meaning which become increasingly esoteric and mystical as they are explored. Like the plans of Gothic Cathedrals, Chinese gardens are cosmic diagrams, revealing a profound and ancient view of the world, and of the man’s place in it. But in their long history they have also been – in a quite real way – the background to a civilization.”

Today, there of thousands of private and municipal gardens in most Chinese cities, but China has three main “Garden Cities” – Hangzhou, Suzhou and Wusih. Hangzhou, the ancient garden city of the emperors, has a history of more than 2,100 years. Marco Polo, one of the earliest foreign visitors to Hangzhou – then called Kin-sai, a name signifying “The Celestial City” – later wrote: “Kin-sai merits preeminence to all other cities in the world, in point of grandeur and beauty as well as from its abundant delights, which might lead an inhabitant to imagine himself in paradise.”

Since that time Hangzhou has suffered cruelly. It was partially destroyed by Genghis Khan and the Mongols in the 13th century and razed again during the Taipei Rebellion in 1862. Fortunately, Premier Zhou Enlai saved the gardens and ancient temples from Mao Zedong’s Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. Today, Hangzhou is a modern city with wide tree-lined streets. Many of the old temples, villas and palaces still stand on the picturesque mountains stretching around the nine-mile shore line of West Lake, which is almost a garden in itself.

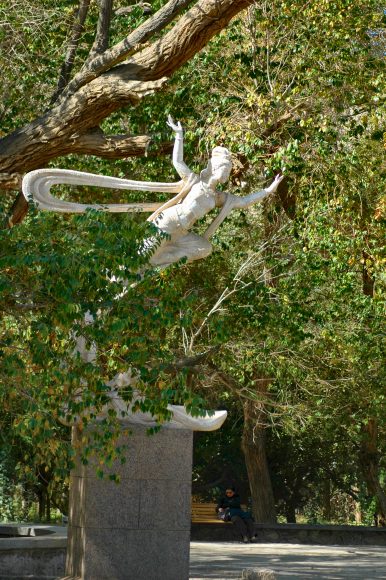

The most famous Chinese garden builders were retired Mandarin scholars. Steeped in classical learning, they found great satisfaction in bringing antiquity alive through the names chosen for their creations. All Chinese gardens, as well as their pavilions and vistas, were given names with long poetic and historical associations, which helps to guide and stir the visitors imagination. Subjects for poetry and paintings enriched these artistic traditions. Without this rich interplay of allusions, the historical flavor and intellectual stimulation of the garden would have been greatly diminished. My husband and I once sailed around Hangzhou’s West Lake in a dragon-shaped gondola to explore the romantic, cloverleaf shaped island called “Three Lanterns Reflect the Moon.” We wandered through the scroll-like Sung dynasty garden, past the “Pavilion of Moon Arriving and Breeze Coming” and over the moon bridges to the “Park of Orioles Singing in the Willows.” In reflections the semi-circular moon bridges, mirrored in he clear waters, complete themselves, producing the ideal round shape – a symbol of the moon and of perfection.

Just as Alice, when she walked through the looking glass found herself in a new and whimsical world, so we, when watching the carp darting through the shimmering lotus blossoms floating on the “Pool to Linger In,” found ourselves as though caught up in some magical time machine and lost all contact with the modern world. We wandered as if in a trance past the golden Buddhas in the “Monastery of the Souls Retreat,” and through the “Caves of the Morning Mists and Sunset Glow,” decorated with 280 Yuan dynasty rock carvings in low relief and covered with the mineral patina and green moss of 700 years. Carved in the 13th century, the carvings represent symbolic animals and the pilgrims that brought Buddhism along The Silk Road, from India to China. Illuminating one cave is the original rock carving of the laughing Buddha, whose mood is still so contagious that visitors get carried away and the sound of laughter echoes from the caves.