Giant pandas seem to exude a mystic power that enchants all who gaze upon them, but this mystical appeal may not be enough to save them. The species remains at extreme risk of extinction, because human activity is shrinking the panda’s habitat.

Since China’s former Chairman Mao Zedong gifted Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing to the Washington National Zoo in the 1970s, giant pandas have become popular all over the world. Animal lovers are smitten by the furry black-and-white creatures with black eyepatches, who resemble teddy bears and can melt your heart at first glance.

Pandas have startling human-like attributes that children of all ages find irresistible. A baby panda has an appealing childlike cry causing its mother to sit up and cradle her suckling baby to her breast while caressing it, like a human mother, with the other forepaw.

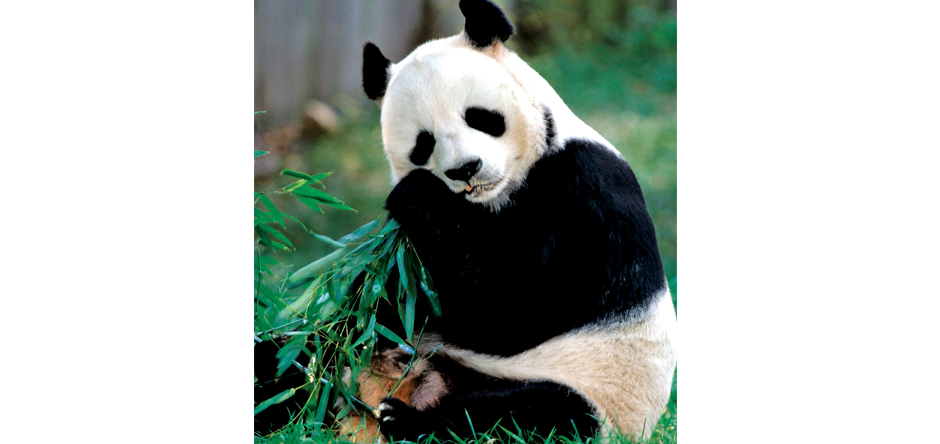

The giant panda is the only bearlike animal with a thumb like humans. Its powerful jaws can sever a stalk of crisp umbrella bamboo in one mighty crunch. Then, rather than lower its mouth to feed like most other four-legged animals, the panda will lean nonchalantly against a tree, peel the bamboo with its thumb and bring it up to its mouth like a child eating ice cream.

For centuries, the Chinese have held giant pandas in special esteem. They were kept in captivity as pets by ancient emperors. Chinese books, written 3,000 years ago, claim the giant panda was endowed with mystical powers capable of warding off natural disasters and evil spirits. The black-and-white patterned panda actually personifies the two great Chinese forces of separation and unity that constitute and balance the universe — the yin and yang, black and white, dark and light, moon and sun, death and life. For thousands of years, farmers have considered them lucky charms or even divine and have refrained from killing the pandas that entered their fields or raided their beehives.

George B. Schaller, a leading panda biologist, noted that the panda is a “perfectly symbolic animal, the embodiment of innocence and vulnerability,” but warned in his book “The Last Panda,” “Humankind has upset the balance, and the panda’s existence is now shadowed by the fear of extinction.” Schaller adds, “Because the panda has become a lucrative commodity, protecting it in the wild seems a near impossible task.”

The main threats to the panda are destruction of its habitat, deliberate poaching for the export of live animals and skins and accidental snaring in traps set for other animals. A live panda sells for $112,000 on the illegal Chinese black market. In Taiwan, Hong Kong and Japan, black marketers are getting $10,000 or more for dead pandas sold as grisly trophies. There are about 300 in captivity worldwide. Although Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing were gifts, Western zoos now pay millions to rent a panda for exhibit. The five pandas in zoos in San Diego, Memphis, Atlanta and Washington, D.C. are here on loan, $8 million for 10 years.

The forbidden world of the giant pandas is known in China as “Hsi-fan,” “the Land of the Western Barbarians.” The World Wildlife Fund, which uses the panda in its logo, reports that the bears’ suitable habitat has shrunk by about 50 percent in the last 20 years. Once they had the freedom to roam in huge coniferous and broadleaf forests, with an understory of bamboo that only grew deep in the remote mountains of central China in alpine valleys with elevations between 5,000 and 10,000 feet. Now they have only six isolated areas where they can find the rare bamboo they thrive on.

Although many types of bamboo exist in China, only two kinds, the fountain and the umbrella bamboo, are hardy enough to grow on the floors of humid ravines and the icy mountain slopes where the giant panda lives. Both species of bamboo appear to follow a 100-year cycle. Roughly once in a century they bloom, drop their seeds and die. In 1975 the entire generation of bamboo died off en masse, leaving the panda without its main food source and no place to go. When the bamboo dies out, the giant pandas succumb to starvation because they lack the ability to move to new areas.

Pandas have existed for millions of years and are believed to have survived the ice age. The origin of the giant panda still remains a puzzle. In 1874, the German zoologist Max Weber pronounced it a living fossil descended from Hyenarctos, a Miocene carnivore. In 1915, A.S. Woodward published a report declaring that a prehistoric giant panda lived 2 million years ago in the Pleistocene Epoch. The first record of the giant panda in Chinese chronicles noted that a “beishung” or white bear was included in the tribute to the Kingdom of Yu from the Kingdom of Chin (Sechuan) in 200 B.C. Although naturalists have now had ample time to study the giant panda in captivity, they cannot agree whether it belongs to the bear family or the raccoon. But recent studies appear to confirm what the ancients have long known: The giant panda is unique.

Although Marco Polo wrote about seeing the skins of black-and-white bears in Emperor Kublai Khan’s Imperial Palace in Peking, the first Westerner to travel into the Hsi-fan and actually see a giant panda was the Jesuit missionary Père Jean Pierre Armand David in 1869. He described Hsi-fan’s difficult terrain in his diary: “For four whole hours we pull ourselves from rock to rock as high as we can go by clinging to roots and trees. All that is not vertical is covered with frozen snow. The inconceivable difficulties of the monkey-like ascent absorbs us so much that we pay no attention to the fresh traces of several large animals in the snow. At last the sun, which has shone till 3 o’clock, disappears in the thick fog, in which we are soon lost.”

During a trip to China in 1975, I, too, trekked into Hsi-fan territory and shivered in the icy forest while attempting to get a photo of the legendary giant panda. I traveled first by horseback and then by foot with some Tibetan farmers, who had recently rescued five pandas from starvation. They said that a number of thin pandas had wandered into their cornfields. They soon found dozens of emaciated carcasses and reported the disaster to local officials, who sent rescue teams. Equipped with ropes and nets they managed to catch dozens of live pandas, but saw dozens more that had pathetically propped themselves against trees with their front paws over their ears to die. The rescued pandas were brought to collecting posts and fed sweet potatoes and rice gruel contributed by the local people, chiefly Tibetans who had lived in the area for centuries. Younger Tibetans scaled the rugged, snow-covered mountains to forage umbrella bamboo to feed to orphaned cubs. The rescued pandas were returned to the forest when the snow melted, except for about 10 that were donated to zoos.

Although we saw broken bamboo and fresh panda tracks in the snow, we never encountered a panda, dead or alive. But I did have the thrill of experiencing the forbidding mountain terrain where these mysterious denizens of China’s primordial forests have roamed since the days of the dinosaurs. I never had the honor to meet a giant panda in the wild, but I did have the opportunity to study at close range the pandas my Tibetan friends had rescued. I was enchanted, awed, yet filled with sadness. It was obvious why these superb creatures have been revered for centuries. They seem to contain the wisdom of the ages. With their aura of mystery, so innocent and gentle, they remained calm and self-contained even in captivity. The realization that this species is slowly slipping off our planet into oblivion because of human encroachment and greed brought a dreadful sorrow to my heart.

The plight of the panda is perhaps the greatest challenge the conservationists have yet faced. There are fewer than 1,500 left in the wild. Schaller tells us that a realistic plan to save the species does exist. “But unless we implement the plan now, our brief pang of love for the panda will end with an eternity for remorse. We must make a global commitment. If we can’t save a spectacular animal like the panda, what the hell are we doing?”