He has been the fault line in American fiction, creating a new style — and a new type of hero — that subsequent writers would either emulate or define themselves against. He was as much a myth of machismo as a man, an invention of his own imagination that foreshadowed our cult of branded celebrity. And though he may not be fashionable today — there are no new scholars of his works, says Mercy College literature professor Christopher Loots — his legacy lies at the intersection of white, male, American identity, gender studies and cancel culture, even as the relationship between his complex character and fine writing begs the question, What price art?

Now America’s greatest film storyteller, Ken Burns, working with longtime collaborator Lynn Novick, has trained his lens on the man who may have been its greatest literary one in “Hemingway,” which will air on PBS at 8 p.m. April 5, 6 and 7. Written by Geoffrey C. Ward and produced by Sarah Botstein, “Hemingway” is a fascinating and at times confounding exploration of Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), to which Burns’ team brings its trademark blend of evocative location shoots, experts’ insights and archival material, with Jeff Daniels as Hemingway and Meryl Streep, Keri Russell, Mary Louise Parker and Patricia Clarkson as his wives.

What writing could be

Any discussion of Hemingway — who grew up in tony Oak Park, Illinois, the son of Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a prominent, nature-loving physician — must begin with his seminal, groundbreaking writing style.

“What Hemingway did and why we study his work is that he made it OK for you to write in a simple, short, refined way,” says Loots, a Ph.D. in English literature with a focus on American and international studies who is teaching a course on Hemingway this semester in Mercy College’s Master of Arts in English Literature Program. “With a writer like Henry James, you’d need a year to get through a paragraph. Hemingway wrote in a shorter, seemingly simple but not simplistic manner that changed the way we think about writing…. He democratized it.”

In this, both Loots and Burns’ documentary note, Hemingway was influenced by the musicianship of his mother, the former Grace Hall, who never let her six children forget that she had given up a career in the arts for them and who taught Ernest, her second-born and older son, to play the cello.

The musicality in Hemingway’s works is defined by a mix of staccato, declarative sentences and longer, more fluid lines threaded by polysyndenton, or the rhythmic repetition of conjunctions “on and on and on,” Loots says. But the author’s crisp style was also honed by the journalistic career that began with The Kansas City Star after high school and would serve as a counterpoint to his fiction; and the influence of Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and other writers of the so-called “Lost Generation” that came of age in World War I and sought to find itself in 1920s Paris.

Writing, however, isn’t merely about the rhythm of language. It’s using that rhythm to capture images and experiences in engaging stories with meaty characters. One of the greatest strengths of Burns’ series is the way he connects the images and experiences of Hemingway’s life — say, camping, fishing and hunting with his father on the lakes and in the woods of northern Michigan — to the typed words on a page.

This is no filmmaker’s conceit. In Paris, Hemingway also absorbed the Modernist paintings of such artists as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Juan Gris, whose shapes and colors distilled emotion and experience.

“Hemingway spoke specifically about the Cubists and the Modernists: ‘I’m trying to do in words what they’re doing in paint,’” Loot says.

“He would spend days, weeks on sentences, going over and over them to find the combination that would put the reader there in the story.”

The visual, the musical, the experiential would all come together in a series of now classic works, including “The Sun Also Rises,” his first novel, about the Lost Generation in Paris; “A Farewell to Arms,” based on his experience as an ambulance driver in World War I; “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” which drew on his coverage of the Spanish Civil War; “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” evoking his adventures as a big game hunter in Africa; and “The Old Man and the Sea,” inspired by his later years in Cuba and for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1952. Two years later, he would be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature — an honor he coveted even as his fragile ego made him feel unworthy of it.

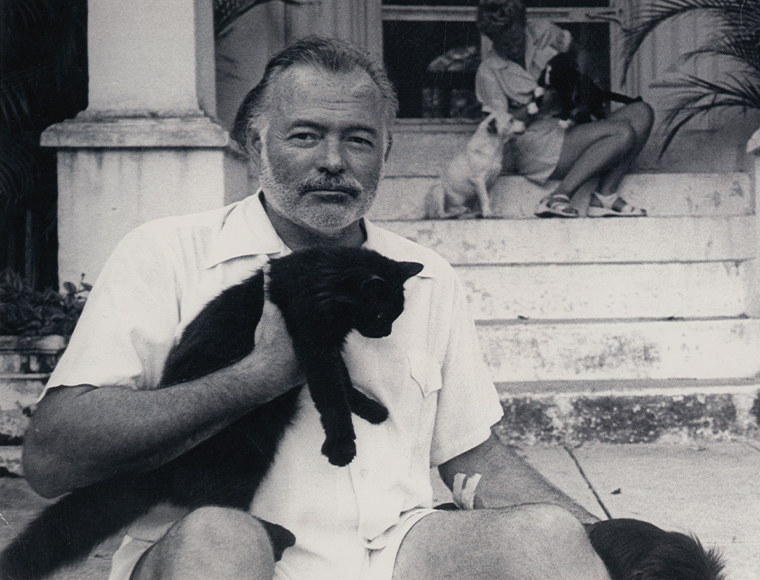

The cat and the bull

Despite that ego, or maybe because of it, Hemingway was simultaneously recreating himself as the Hemingway man — risk-taking, hard-drinking, globe-trotting, big game-hunting, bullfight-watching, gun-toting and woman-loving, which is not the same as being a lover of women. He liked to be called “Papa,” even though Loots says he didn’t want to be a father. (Ultimately, he threw himself into the role as the father of three.)

For all “Hemingway’s” literary analysis with scholars like Mary Dearborn and Mark Dudley and such writers as Edna O’Brien and Mario Vargas Llosa, what will draw viewers and keep them there is its tale of a complex man — brilliant yet sometimes sexist, racist and anti-Semitic in his fiction and nonfiction works; back-stabbing to helpful friends and colleagues; and often brutal to his children and four wives, the last three of whom were journalists — Hadley Richardson, the love of his youthful Paris days and mother of son John; heiress Pauline Pfeiffer, the mother of sons Patrick and Gregory; Martha Gellhorn, who left him for her identity as a single career woman; and Mary Welsh, the keeper of his flame.

In perhaps the documentary’s most telling moment, Hemingway excoriates Gregory for causing Pauline’s collapse and subsequent death in 1951 after she bailed her younger son out of jail in Los Angeles for cross-dressing. (In reality, Pauline died on the operating table of a burst, previously undetected adrenal gland tumor, though the release of adrenaline from the stress of the incident may have been a contributing factor.) Gregory — who would later alternate between his identities as Greg, father of eight, and Gloria — wrote a response that goes to the heart of what we today call cancel culture: Were his father’s achievements worth devastating the lives of his four wives and three children?

Can an artist’s or athlete’s accomplishments be separated from who and what he is? It’s a question each person must answer for himself, Loots says, though he suggests that when it comes to Hemingway the writer, we take Hemingway the man out of the equation.

“He’s something different from the macho myth, which he manufactured,” Loots says. “In his stories, there’s a gentleness and a quality that is antithetical to the alpha male machismo.”

Often, he adds, Hemingway identified with the unloved woman — as in his short story “Cat in the Rain,” in which the title animal serves as a metaphor for a neglected wife — and explored gender role-playing and androgyny, both in works like “The Garden of Eden” and in his marriage to Mary,

This fluidity appears in his love of cats, emblems of feminine grace — some 50 of which still roam the Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West — and his fascination with bulls, protean symbols of masculinity and suffering.

It is suffering and the ability to endure that galvanize Hemingway’s works, Loots says.

“In ‘A Farewell to Arms,’ he wrote, ‘The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.’”

Hemingway himself broke for good on July 2, 1961 when he put a shotgun to his head at his home in Ketchum, Idaho, 19 days before his 62nd birthday. Experts now attribute his suicide to the debilitating mental and physical effects of alcoholism, concussions and hereditary haemochromatosis, in which the accumulation of iron in the body leads to mental and physical deterioration. Perhaps, too, the myth, which was now overshadowing the work, had engulfed the man.

Humans are bound to suffer. But as Hemingway’s first book suggests, the sun also rises every day. “Maybe,” Loots says, “we are stronger for having suffered.”

For more, visit pbs.org and for more on Christopher Loots’ fall class, “The Literature of the Left Bank, Paris,” visit mercy.edu.