As befits the second largest financial district in the metro region, after the Big Apple, Stamford has an appropriately button-down history, albeit one that zigs and zags its way ever upward from its native beginnings as Rippowam – the name, according to the Stamford History Center, was changed in 1642 to honor a town in Lincolnshire, England, which supplied more than 80 percent of the original settlers to New England – to its present as a stronghold of corporate and personal wealth. But the story behind that ascent is one of alleged witches and would-be pirates, mysterious astronomical events and a murder trial that would “Boomerang” from Connecticut to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s White House and back.

This is the Stamford that few people know, a portrait of a city tested by prejudice and hysteria that would see reason triumph. In dark days, including the literal “Dark Day,” Stamford shone a light:

Something fanciful this way comes

The Salem, Massachusetts, witch trials are a justly infamous part of American history, but in the same year they began, 1692, witch hunting came to Stamford. It began with Katherine Branch — a French servant of the Wescot family, who lived along the shoreline near Wescot Cove and whose story is captured in Richard Godbeer’s “Escaping Salem: The Other Witch Hunt of 1692” (2005).

One fine April day, Branch picked some herbs, came home and collapsed, clutching her chest. Branch started having fits and babbling about shapeshifting cat-women tempting her with the good life. (Was it epilepsy or some neurovascular disease, or was it something in those herbs? Maybe she was just looking for some attention and escape from what must’ve been a dreary existence.) At any rate, Branch put two and two together, came up with five and eventually declared witchcraft to be the cause. A month later, she accused Elizabeth Clawson — a neighbor who had had a disagreement with the Wescots about the weight of flax — of being a witch, as well as Mercy Disborough, who was apparently everyone’s go-to for witch accusations, and a handful of others.

While the time-honored tests for witchcraft were employed — including throwing the accused in a body of water to see if she would float — jurisprudence proved decisive. Clawson’s husband, Jonathan, did what any good husband would do: He got together a petition of 76 brave individuals who affirmed his wife’s fine character. That was no doubt key to her acquittal at trial. (Disborough was found guilty but got off on a technicality when a juror missed a meeting.)

Unlike the more pervasive witch trials in Salem — in which 200-plus were accused, 30 found guilty, 19 hanged, one pressed to death for refusing to plead and at least five died in prison — the Stamford witch trials damped down hysteria. Reason and the antecedents of the American judicial system prevailed.

Ahoy, mercantile mateys

If we had a dollar for every time we heard someone say that Capt. Kidd’s treasure was buried in the Hudson Valley or along Connecticut’s Gold Coast, we’d all be rich. That’s because William Kidd (circa 1654-1701) — a Scotsman who climbed New York’s social ladder before turning to privateering — disposed of his goods, ill-gotten and otherwise, on his way back from the Caribbean to New York in 1699. Some of the treasure reportedly went to Gardiner’s Island in East Hampton. But that hasn’t stopped legends from cropping up about reported Kidd bounty in Milford and Westport, among other locales.

Wherever the booty was stashed, Kidd took the knowledge to his grave. Richard Coote, the first Earl of Bellemont and royal governor of New York, New Hampshire and Massachussetts Bay — a Kidd investor who didn’t want to be tarnished with the same pirate’s brush — lured him to Boston with the hope of clemency and ultimately had him extradited to England, where he was hanged for murder and piracy in 1701.

It was Bellemont who would provide the Stamford connection, according to the Stamford History Center, in a report to the English Lords of Trade: “There is a town called Stamford in Connecticut colony, on the border of this province, where one Major (Jonathan) Selleck lives. He has a warehouse close to the sea, that runs between the Mainland (Long Island). That man does great mischief with his warehouse, for he receives abundance of goods from our vessels, and the merchants afterwards take their opportunity of running them into this town. Major Selleck receives at least ten thousand pounds worth of treasure and East India goods, brought by one Clarke of this town from Kidd’s sloop and lodged with Selleck.”

Of course, the to-ing and fro-ing of goods between Stamford and New York City was from the beginning one of Stamford’s chief industries, along with fishing and farming (potatoes, wheat, corn, rye, oats and livestock). What seems to have twisted Bellemont’s breeches, again according to the history published at stamfordhistory.org, was that “Selleck was evading English taxes even before it was a political statement.”

Stamford’s — and Connecticut’s — ‘Dark Day’

If there was a golden boy in the history of Stamford, it would be Col. Abraham Davenport. Scion of the Davenport family — he was the grandson of New Haven colony founder John Davenport — Abraham graduated from Yale University, married twice, led the Patriot cause in Stamford during the American Revolution, cared for surviving solders long before there were organizations like Wounded Warriors and served in various municipal and judicial capacities while amassing great wealth. But May 19, 1780 may have been his finest hour. It was the day that darkness descended over New England and part of Canada, which scientists attribute to drought and forest fires that year. The God-fearing members of the Connecticut Council, or State Senate, believing the end was nigh, fell to their knees and wished to adjourn — all but Davenport. “I am against adjournment,” he said. “The day of judgment is either approaching, or it is not. If it is not, there is no cause for an adjournment; if it is, I choose to be found doing my duty. I wish therefore that candles may be brought.” The candles were brought and deliberations continued.

Davenport’s grace would inspire the Depression-era painting “Dark Day” by Delos Palmer and President John F. Kennedy, who often referred to Davenport’s courage on the campaign trail in 1960. It also spurred John Greenleaf Whittier to write in his 1866 poem “Abraham Davenport (Tent on the Beach)”:

And there he stands in memory to this day,

Erect, self-poised, a rugged face, half seen

Against the background of unnatural dark,

A witness to the ages as they pass,

That simple duty hath no place for fear.

‘Boomerang’

A murder that shocked Bridgeport almost 100 years ago to this day reverberated from Stamford to the White House and back again.

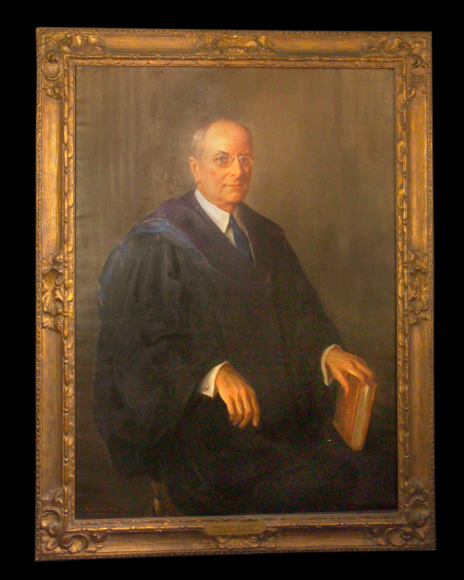

At 7:45 p.m. Feb. 4, 1924, Rev. Hubert Dahme, beloved pastor of St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church, was shot in the back of the head by a man wielding a .32-caliber gun amid an array of busy theaters on Main and High streets. A week later, police arrested Harold Israel, a former soldier and vagrant who possessed a .32 caliber gun and was placed at the scene. Israel would ultimately confess to the crime. It would seem then to have been a slam dunk for Homer Stillé Cummings, an ambitious Stamford lawyer and former mayor of the city who was the state attorney in Fairfield County and who had led a life as charmed as the impoverished Israel’s wasn’t.

But when Cummings entered the courtroom that Feb. 15, he argued that the state had the wrong man. The confession by the sleep-deprived, psychologically spent Israel had been forced. Witness testimony turned out to be suspect. Ballistics proved Israel’s gun was not the murder weapon. And his description of the shorts he said he was watching in a nearby theater at the time of the murder was confirmed by the theater’s manager.

Instead of a conviction, the prosecutor engineered a stunning nolle prosequi (“we shall no longer prosecute”) in the name of justice. In a fascinating 2017 study of the case for Smithsonian magazine and The Marshall Project, author Ken Armstrong quotes the late Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter as saying that Cummings’ performance “will live in the annals as a standard by which other prosecutors will be judged.” But the strange case — which was never solved — was not finished yielding its twists.

Cummings would go on to become President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first attorney general. As such he would instigate Roosevelt to pack the Supreme Court with justices favorable to FDR’s New Deal for an economically depressed nation — a power grab that ultimately backfired. Though he had been a progressive mayor, as the nation’s chief prosecutor Cummings refused to apply a federal law to lynchings.

Yet he was praised for consolidating federal investigators into the FBI; building the Alcatraz prison and announcing the capture of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping of the Charles Lindbergh baby. He would also develop a friendship with Israel, who returned to his native Pennsylvania to become an upstanding citizen and family man. Cummings would even help Israel negotiate the sale of his story to the movies.

The resulting film, “Boomerang,” was filmed mainly in Stamford when Bridgeport declined, with the courtroom scenes shot in White Plains. It premiered March 5, 1947 with Dana Andrews, who starred as the Cummings character, and director Elia Kazan in attendance.

Cummings died in 1956 at age 86; Israel, eight years later at age 60. Cummings’ name is on a Stamford park, a law firm (Cummings & Lockwood) and a Connecticut prosecutorial award.

But Armstrong suggests that his greatest legacy may have been Israel’s numerous descendants. For as Israel’s widow Olive always said, without Cummings, none of her family would be here.