He is, in a sense, the reverse-Nureyev.

Whereas Rudolf Nureyev was all darkling Dionysian fire on the ballet stage, David Hallberg – pale and blond, with long, lean limbs – possesses an Apollonian cool that would suit him in, well, George Balanchine’s “Apollo.”

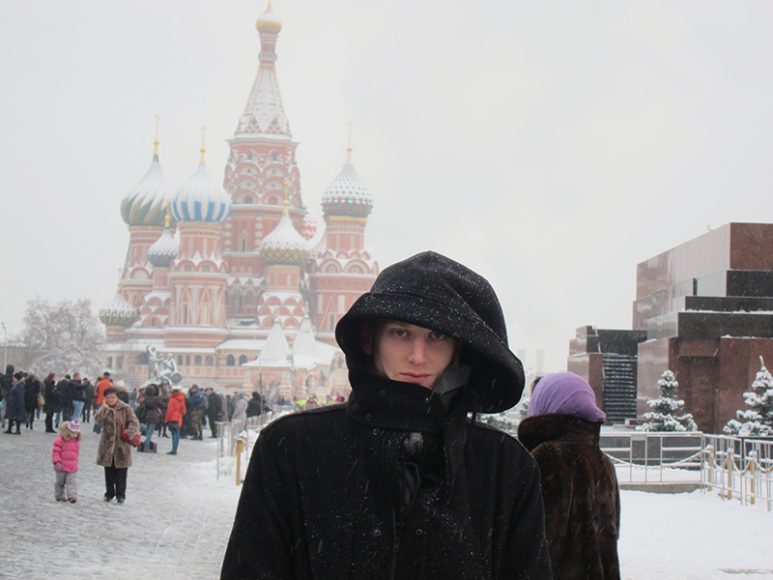

Their trajectories are mirror images, too. In 2011, Hallberg, a principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre, joined the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow — the first American to do so — a half-century after Nureyev made his leap from behind the Iron Curtain to dance in the West.

Hallberg’s “defection” wasn’t quite as dramatic as Nureyev’s standoff with Kirov Ballet officials and his KGB minders at Le Bourget Airport in Paris. “I just got on a plane,” Hallberg says. But like Nureyev, he is proving to be a trailblazing crossover artist — starring in a video for Nike and sporting Jean Schlumberger’s Bird on a Rock clip for Tiffany & Co.’s fall ad campaign.

Indeed, he tells WAG that what inspired him about Nureyev wasn’t his dancing “but a biography of how he lived his life. It was his insatiable curiosity that inspired me. You have to look all around you to become complete.”

Hallberg echoes that thought later in a conversation with choreographer Peter Pucci before an audience at the Jacob Burns Film Center in Pleasantville: “Risk was it. For me as an artist, I’ve always thrived on that risk, the unknown.”

The occasion of his comments is the first selection in the Burns’ annual “Dance on Film” series, the fascinating 2015 docudrama “Rudolf Nureyev: Dance to Freedom,” in which Bolshoi Ballet star Artem Ovcharenko captures Nureyev’s androgynous good looks and singular self-possession amid an alternately tense and amusing Cold War setting that resonates in today’s political climate.

“He is one of the most warm-hearted, easiest to get along with guys,” Hallberg says of Ovcharenko, “and I’m so happy for him. No one is more deserving of this opportunity. He’s a beautiful dancer with long lines.”

The Burns’ screening is also the occasion of a signing for Hallberg’s new memoir, “A Body of Work: Dancing to the Edge and Back” (Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, $28, 424 pages), an astonishingly candid and evocative portrait of an artist who — despite childhood bullying, a peripatetic lifestyle that has required constant cultural readjustment and a career-threatening injury — is never less than comfortable in his own skin.

Certainly, that centeredness — akin to Nureyev’s — stood him in good stead during his three years (2011-14) in Moscow. Fast-paced, formidable and forbidding, Moscow, like New York, is not a place where the meek shall inherit the earth. In Hallberg’s telling, you can feel the pressure of impatient shoppers at the supermarkets and the disdain of the checkers as your credit card fails to work the second time. And you can practically smell the cat urine at the Bolshoi Theatre — the result of what Hallberg calls feline Phantoms of the Opera — and see its creamy Corinthian columns, topped by a pediment crowned with Apollo driving his steeds.

A tough, imposing town. “But as I make very clear in the book, I was never mistreated,” says Hallberg, who had been there a dozen times before. “There was no anti-Americanism, no harm, no stereotyping.”

In contrast to his days at the Paris Opera Ballet School — where he was scornfully known as l’Amérique, “the America” — he says, “Everyone involved in the Bolshoi was welcoming.”

And in Hallberg — who blends a subtly immaculate technique with a soulful acting style — the Bolshoi had a sponge waiting to soak up all the company had to offer, including a bold, visceral style that is often contrasted with the refined classicism of the Kirov, to which Hallberg would seem better suited.

“I was so happy to learn how to use my body in a different way,” Hallberg says. “I didn’t want to lose my identity as a dancer, but I wanted to absorb the style.”

In Russia, ballet dancing is not considered an unmanly profession, as it is still, unfortunately, in the United States. Yet President Vladimir Putin’s anti-gay agenda has been well-documented. Nevertheless, Hallberg — who writes frankly about his sexual awakening as a gay teen and the brutal bullying he endured growing up in Phoenix — was never harassed in Moscow. As he made friends among the city’s artists, it opened up to him — reminding us that it’s not where you are so much as who you’re with

where you are.

At the banya, or sauna — where Hallberg would go on his day off to ease his aching limbs — he and the other dancers had a special status. In one of the book’s most poignant moments, an acquaintance named Genia musters the courage to ask him for tickets to the Bolshoi as a treat for himself and his girlfriend on Woman’s Day.

“Like many Russians,” Hallberg writes, “he had been told as a child that maybe one day, instead of watching Bolshoi on TV, he could actually see a live performance at the historic theater….It gave me as much fulfillment to give Genia those tickets as receiving the tickets gave him.”

Moscow has not been the only “M” city to loom large in Hallberg’s life and memoir. Melbourne played a big part after he was sidelined in 2014 by an injury to his left ankle that required two surgeries. Dancers measure the length of their careers in dog years. “I lost two and a half years,” he says. “That’s 15 years in the dance world.”

But it was more than that, he adds: “I lost everything that defined who I was.”

He shaved his fine blond mane — “like shedding an old skin” — and moved to Australia, where he rehabbed and hung out in pubs.

“I never had my college years,” he says. “I always had to get up the next day (for dance class). So it was nice to sit in a pub and talk to the bartender.”

Today, Hallberg is back with ABT, performing with the company during the past spring season. He’s also a resident guest artist at The Australian Ballet, appearing there twice a year. Next year sees him guesting with The Royal Ballet, while at ABT, he and Natalia Osipova — with whom he has an electric, complementary partnership — will perform “Giselle” on May 18, their birthday.

“I feel like a completely different artist. I use the word ‘rebirth,’” he says. “You don’t know gratitude until something has been taken away from you.”

He is paying that gratitude forward with the David Hallberg Scholarship for boys aspiring to ballet careers.

“I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t fit in,” Hallberg says of the bullying. Dance became his safe place and the passion for dance the overwhelming counterweight to others’ expectations.

“That’s why having come out the other end, I’m determined to help boys in ballet. I can say, ‘I went through this.’”

And triumphed.

For more, visit davidhallberg.com.