When Nicholas D. Kristof was a child, he rode the Number 6 school bus with the five children of the Knapp family in Yamhill, Oregon — a farming community of golden wheat, Christmas trees and spreading orchards of apples, cherries and hazelnuts.

The Knapps had been itinerant fruit pickers who managed to become homeowners through husband Gary’s union pipe-laying job and wife Dee’s work driving a tractor. Their bright brood — led by Kristof’s Yamhill Carlton High School classmate Farlan, “adept with his hands and smart, a natural engineer” — was on a trajectory to surpass preceding generations in education, with high school graduation and college in their sights.

However, when Gary, an alcoholic wife beater, died at 39, the Knapps, like others in their community, found themselves falling off the tightrope of patriarchal, working-class America, in which any one problem — the loss of a breadwinner, usually the husband; a parent’s drug addiction — could send a family on a downward spiral of dropping out of school, un- or underemployment, substance abuse, mental illness, incarceration and early death.

“I think back to my friend,” Kristof says of Farlan, a woodcarver and furniture maker whose drug and alcohol abuse led to liver failure. “Those five kids were all smart. But four out of five of them are dead. I wonder if I might’ve been like Farlan had our circumstances been reversed.”

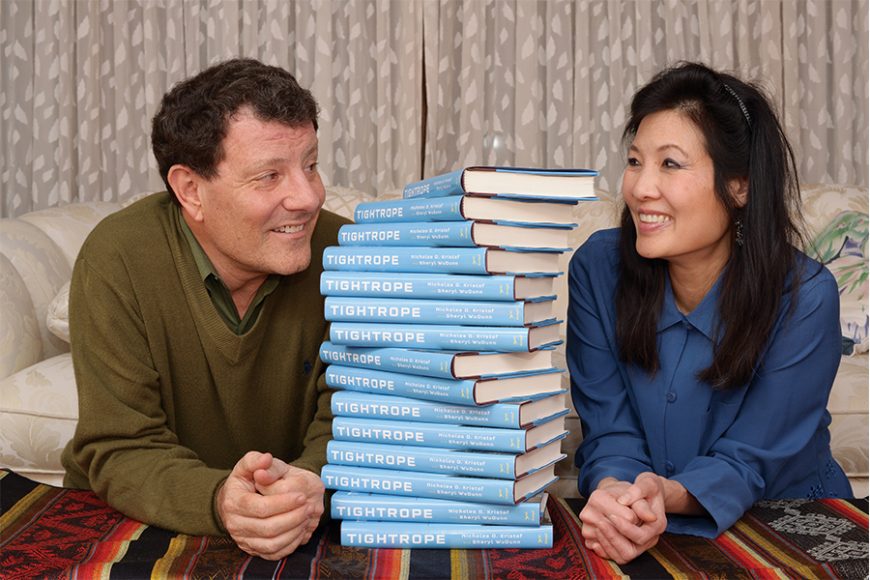

Instead, Kristof — the Chicago-born son of Portland State University professors, who grew up on a sheep and cherry farm — would go on to Harvard and Oxford universities, the latter as a Rhodes Scholar, and a career as a foreign correspondent and associate managing editor of The New York Times. In 1990, he and wife Sheryl WuDunn, who served as a foreign correspondent and business editor with The Times, became the first married couple to win a Pulitzer Prize for journalism for their coverage of the uprising in China’s Tiananmen Square. (He garnered a second Pulitzer in 2006 for his columns on war-torn Darfur, Sudan.) With WuDunn, who now works in finance and consulting, Kristof has written four books on the subjects of China and women’s rights.

Their fifth, published last month by Alfred A. Knopf, considers what happened to their friends back in Yamhill and working-class people like them around the United States. “Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope” ($27.95, 304 pages) is a timely work and, thus an important one, given that the erosion of the American working class was a decisive factor in the 2016 presidential election and will undoubtedly play a role in the 2020 one as well. At its heart, the book offers a counterpoint between nature and nurture, personal responsibility and collective obligations. That counterpoint is central to the decline of the working class, they write.

“One of the root causes was a change in the narrative that began in the 1970s,” says Kristof, a Westchester resident who will join WuDunn for a book talk at Scarsdale High School on March 11. “Everything was about personal responsibility and the idea that helping people would create dependency.”

But aren’t people responsible for their own actions? Kristof acknowledges that “there are bad individual choices. What’s most important are the bad choices society has made.”

Both he and WuDunn point to the lack of a safety net in the United States, noting that auto workers who were laid off in Ontario, Canada, during the Great Recession of 2008-09 made out better than their Detroit counterparts in large part because they retained their health benefits and had access to better job-retraining programs.

“Ultimately, we need health care for all,” WuDunn says. Kristof agrees: “I would add that what’s important is universal health care. It’s less important if it’s single payer, as in Britain, or multiple payer, as in Germany.”

Complicating the lack of health care and the deterioration of the working class is what WuDunn calls “a hostility toward labor unions,” which is often eclipsed by management in their battle for workers’ rights and benefits and have themselves made mistakes.

The couple also sees a lack of education as crucial. “There is an anti-intellectualism that is permeating the country,” observes WuDunn, who holds a B.A. from Cornell University, an M.B.A. from the Harvard Business School and an M.P.A. from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. What we need, she adds, is early childhood education so that kids can get a jump on higher learning, as there is a great socioeconomic divide between those who have a bachelor’s degree and those who don’t. The only way this will happen, Kristof adds, is if we have a more egalitarian system so that poorer kids have the same access to quality education that wealthy kids do.

For some, education will mean job retraining, the couple says. But that doesn’t mean we should undervalue the contributions workers have already made to society. We must, the couple adds, understand the part that lost jobs play in shaping identities. “President Trump did speak to (workers’) sense of despair” about the loss of both, Kristof adds, but then he undercut the narrative by cutting back their health care.

Kristof and WuDunn paint a portrait of a country at a crossroads, one whose mediocre standings in education, life expectancy and psychological satisfaction do not justify its overconfidence. It is in many ways a grim picture. But the subtitle speaks of hope and there are shining moments, including the example of Mary Daly, a suburban St. Louis high school dropout, who, thanks to the helping hands of a guidance counselor and a college teacher named Betsy Bane, would earn a bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. in economics. Today she is president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, “one of the most powerful shapers of economic policy in the United States,” “Tightrope” quotes The Washington Post’s Heather Long as saying.

Mentorship is the first of the book’s “Ten Steps You Can Take in the Next Ten Minutes to Make a Difference.” The others are sponsoring a child through Save the Children; getting involved with a nonprofit like Targeting Our People’s Priorities with Service, Provoking Hope and Women in Recovery; supporting early education for at-risk kids; becoming an advocate for a favorite cause; encouraging your book club or another group to tackle an issue; volunteering at a homeless shelter; discussing a taboo subject like mental health; and rewarding moral companies and punishing immoral ones with the power of the wallet.

Finally, Kristof and WuDunn suggest making an individual difference. In this they are walking the talk, deciding to replace the failing cherry orchard on the family farm in Yamhill with cider apples and wine grapes that are already yielding job opportunities.

“It’ll be a risk and an adventure,” they write, “but we’re also excited to create a pathway that just might help a community that we cherish.”

Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s “Tightrope” talk and book signing at Scarsdale High School is set for 7 p.m. March 11. For more, visit penguinrandomhouse.com and kristoffarms.com.