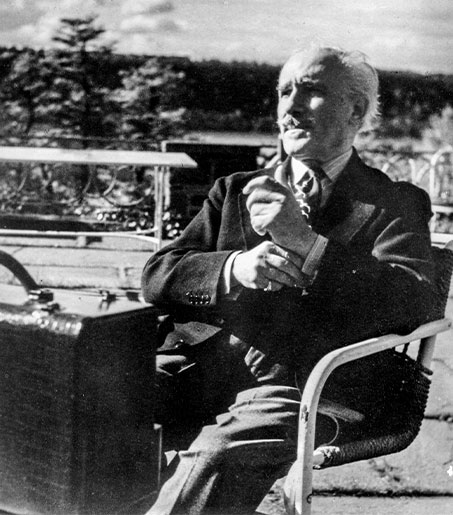

As with all the great historic houses that preside over the banks of the Hudson River, Wave Hill — now a public garden and cultural center in the Riverdale section of the Bronx — has been no stranger to illustrious visitors (Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother) and residents (the young Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain). But of all the celebrated and powerful who strode the rooms of its Greek Revival manse, Wave Hill House, and savored its conservatory, gardens and scenic pergola, few were more fascinating than fiery maestro Arturo Toscanini, whose authoritative passion, acute ear, attention to detail and photographic memory have made his name a benchmark of classical music conducting.

Toscanini (1867-1957) was already an international sensation with conducting stints at the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic on his résumé when talent, temperament — and a very different kind of musical titan — conspired to set him on the serpentine path that would lead from Manhattan to the promontory that is Wave Hill.

The year was 1936 and Toscanini, having wrapped up a decade on the podium of the New York Phil, was ready to retire in his native Italy, where the political situation remained explosive. Already Toscanini, who had flirted with Fascism in the 1920s, had tangled with dictator Benito Mussolini — refusing to play “Giovinezza,” the Fascist anthem, at Teatro alla Scala in Milan and enduring physical attacks, wiretaps, surveillance and passport confiscation. “The conduct of my life has been, is and will always be the echo and reflection of my conscience,” Toscanini observed — although his passionate nature might’ve gotten the better of him when he thundered to a friend: “If I were capable of killing a man, I would kill Mussolini.”

So when emissaries and mutual friends of David Sarnoff came calling with an overture for a new musical venture in New York, Toscanini was reluctant but ripe.

Scarsdale resident Sarnoff — president of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and the dealmaker behind the creation of its fledgling TV network, NBC — wanted a symphony orchestra that would bring classical music to the masses, and he wanted Toscanini to conduct it. The NBC Symphony Orchestra made its debut on Christmas 1937 from Studio 8H at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan, now the home of “Saturday Night Live.”

The concerts, while overall successful, making Toscanini a household name, were not without their challenges. The acoustics were famously dry and the maestro was criticized for adhering too rigidly to the scores — something that composers, of course, loved — and for not playing enough modern and American music. The last criticism was unfair as Toscanini played works by Cortlandt Manor resident Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, John Philip Sousa and Dimitri Shostakovich while showcasing such soloists as clarinetist/band leader Benny Goodman, the witty pianist Oscar Levant and the virtuoso pianist Vladimir Horowitz, who happened to be married to the maestro’s younger daughter, Wanda.

On Nov. 5, 1938, Toscanini conducted the premiere of what would become one of the most famous of American works, an orchestral arrangement of the second movement of Mount Kisco resident Samuel Barber’s String Quartet, Op.11, the “Adagio for Strings,” better known today as the soundtrack for “Platoon.” Toscanini pronounced the work semplice e bella — “simple and beautiful.”

A personnel dispute with Sarnoff led to Toscanini’s brief resignation from the orchestra in 1941. He would share conducting duties with friendly rival Leopold Stokowski before resuming complete control in 1944. It was during these crucial World War II years that Toscanini lived at Wave Hill. Online footage at Critical Past https://www.criticalpast.com/video/65675025691_Arturo-Toscanini_plays-piano_works-on-a-musical-composition_makes-a-correction offers a glimpse into the maestro’s life there. As his grandson Walfredo — son of Toscanini’s only son, Walter, and a future deputy mayor of New Rochelle — lounges in a study filled with books, plants and memorabilia, Toscanini paces, listening to a phonograph, then annotates a score at a piano. Outside nature would create a different kind of thunderous sound, the wind howling across the river.

“I believe we have the noblest roaring blasts here I have ever known on land,” said Mark Twain, who lived at Wave Hill some 40 years before Toscanini (1901-03). “They sing their hoarse song through the big treetops with a splendid energy that thrills me and stirs me and uplifts me and makes me want to live always.”

None of us do, of course. Toscanini would leave Wave Hill at the war’s end in 1945 but would stay on in Riverdale, continuing to conduct the orchestra at Studio 8H until 1950, then briefly at Manhattan Center and finally at Carnegie Hall. His last performance, an all-Wagner program on April 4, 1954, caused a sensation when the maestro had a minor lapse in concentration that led panicky technicians to stop broadcasting the concert for a full minute, even though Toscanini quickly regained his form.

While he would spend the next few years evaluating the broadcasts with Walter for release on record, that lapse was a harbinger of things to come. Toscanini had a stroke on New Year’s Day 1957 and died on Jan. 16 at home in Riverdale. He is buried in Milan in the family tomb, with an epitaph that reads Qui finisce l’opera, perché a questo punto il maestro è morto.” (“Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died.”)

Thirty-one years earlier, he had uttered those words before Liù’s death scene in Act III of Giacomo Puccini’s “Turandot” during the opera’s premiere at La Scala, because that was was all the music Puccini had composed before he died. (The next night, La Scala would present a full performance of the work, the opera having been completed based on Puccini’s remaining notes and sketches.) But at that first performance when Toscanini spoke, he had laid down his baton.

Now he laid it down for good. Wave Hill, however, would go on singing. Since becoming a public garden in 1965, the site has also become the home of programs in which the arts intersect with nature. Gyan Hur’s “So we can be near” installation (May 22-June 27) deals with landscape, beauty and loss. Simultaneously, Shoshanna Weinberger’s “Fragments of Perception” plumbs Wave Hill’s Aquatic Garden Pool and tropical plants collection as well as her own Caribbean-American heritage. Then “The Shadow of the Sun: Ross Bleckner and Zachari Logan” (May 22 through Aug. 15) finds two complementary, longtime collaborators teaming again to consider the themes of invisibility, queerness, the landscape and the fragility of life.

There are free, popular weekend programs that allow families to create art around nature-inspired themes and lots of live music.

In other words, Wave Hill is the kind of place where the spirits of people like Twain and Toscanini can “live always.”

For more, visit wavehill.org.