Every nation creates its own distinctive culture expressed in its literature, music, art, architecture and design, which is usually inspired by the surrounding environs.

In my extensive travels, the most innovative designs I have ever encountered were created in one of the most improbable places on this planet. It is known locally as Druk Yul and to outsiders as Bhutan, Kingdom of The Thunder Dragon.

I experienced these exotic and whimsical designs in 2002, when the Gangtey Rinpoche — high lama of the Gangteng Monastery in Bhutan, who is believed to be the ninth incarnation of the Buddhist patron saint Pema Lingpa — invited me to come to Bhutan and photograph a festival of lama dances to raise funds for the temple’s first restoration. I was delighted to accept and soon discovered that the mysterious monastery, founded five centuries ago, stands close to heaven in a scenic valley in the Himalayan Mountains.

Bhutanese believe that Buddha was born of a lotus and this distinctive monastery is akin to the heart of a lotus blossom while the surrounding mountains cup it like frosted lotus petals. Today it is one of the holiest Buddhist sites in the world.

Bhutan, the last Buddhist kingdom in the Himalayas, is about the size of Switzerland, with a population of some 700,000. The tiny country is sandwiched between two giants, China and India. But despite Bhutan’s location, the art and design found there is unique, perhaps because this “Mountain Fortress of the Gods” remained closed to the outside world until 1974.

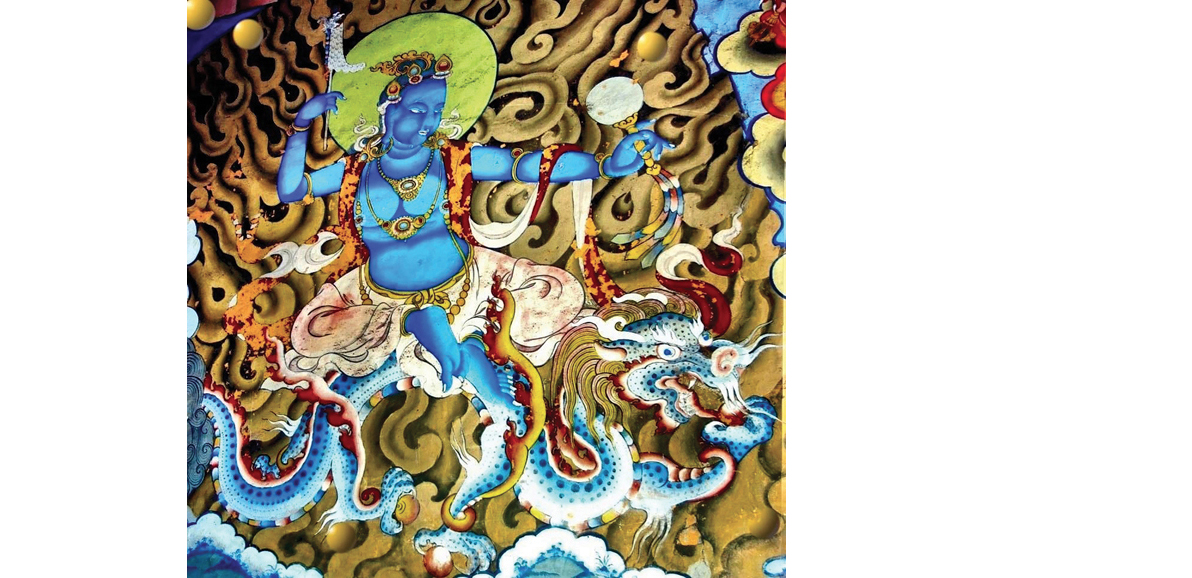

The best examples of Bhutan’s designs can be seen in the details of the ancient murals that flank the entrance to the Gangteng Monastery. They depict 12 semi-enlightened goddesses who became “Protectors of the Snowy Mountains.” To this day, they ride the skies over the Himalayas mounted on mythical beasts, including a dragon, a mythic bird called the garuda, and a multiheaded tortoise.

Bhutanese art and design capture an inimitable paradox of the kingdom’s culture, in which erudition and shamanism co-exist. The Buddhist nature of Bhutan’s artistic heritage may be traced to the founder, St. Pema Lingpa, who was an accomplished artist and architect. The shamanistic aspect was inherited from the ancient Bon religion, a complex blend of nature worship, superstition and the supernatural involving evil and benevolent spirits dwelling in space, mountains, forests and lakes. The Bon belief flourished for centuries until one auspicious day, in the eighth century, when a bizarre miracle occurred. The mythological Buddhist saint and Indian mystic, Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) flew from Tibet, via Swat in present-day Pakistan, to the Kingdom of The Thunder Dragon on the back of a flying tiger to bring Buddhist dharma and other teachings to Bhutan. If you can’t believe that, don’t go to Bhutan.

According to legend, the Bon king got into a mess of trouble with the gods and beseeched the Tibetan Guru Rinpoche for assistance. The guru agreed to make peace by bringing Tibetan Buddhism to Bhutan. He was eventually able to merge Bon with Buddhism by integrating the numerous Bon gods embodied in natural phenomena with Buddhist deities, many inherited from Hinduism.

But it wasn’t easy. After fighting 12 legendary battles, in which the guru appeared in eight malicious manifestations, he conquered the wrathful Bon gods. Then instead of slaying them, he granted them Buddhist mercy. In gratitude, they swore oaths to safeguard Buddhism.

Although the frescoes on Gangteng Monastery were painted almost 500 years ago with traditional paints made from earth minerals and vegetables reduced to powder and mixed with water, glue and chalk, they have been well-preserved in the dry mountain air. The brushes were composed of twigs and yak hair. The colors were applied in a particular order, laden with symbolic meaning, on a thin layer of cloth glued to the wall using a special paste. In recent times, chemical colors are sometimes used but all the restoration work in the Gangteng was done in the original way.

The murals are visually stunning but the issue of whether Buddhist art is beautiful or not is irrelevant to its intended purpose, which is to teach, by symbolism, the way to spiritual experience of which the painting is only the outward visible sign.

Traditional Bhutanese art and design, then, has two characteristics: it is religious and anonymous. Disciples of a master did all the preliminary work, while the fine work was executed by the master himself.

The art was contained in immense fortress monasteries called dzongs, extraordinary exemplars of Bhutanese architecture that stretched along strategic mountain ridges. These fairy-tale citadels dominate the major valleys and serve as administrative headquarters for secular and religious authorities. Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal unified Bhutan in the 17th century and built most of the dzong, which were all constructed on general design principles but with unique details. The architects relied on a mental concept for design and never used blueprints or nails. Yet every inch of the interiors, window sills, ceiling beams and columns burst with flamboyant traditional and abstract designs.

That was the true Bhutanese miracle.