Could the American Revolution have turned on a particularly engrossing game of chess?

It’s possible, according to one legend.

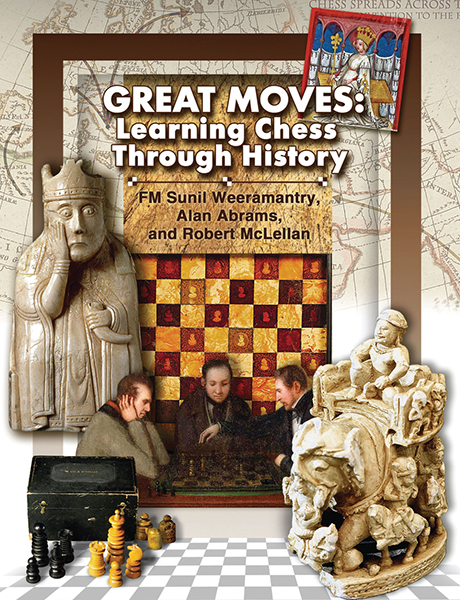

Sunil Weeramantry recounts the story in a recent interview with WAG. It’s also featured in “Great Moves: Learning Chess Through History” (Mongoose Press, $29.95, 371 pages), which he co-authored with fellow White Plains resident Alan Abrams and Robert McLellan.

Sunil Weeramantry recounts the story in a recent interview with WAG. It’s also featured in “Great Moves: Learning Chess Through History” (Mongoose Press, $29.95, 371 pages), which he co-authored with fellow White Plains resident Alan Abrams and Robert McLellan.

Before George Washington led his famed crossing of the Delaware River to attack Trenton, New Jersey, in December of 1776, a spy had sent word of the impending attack to the commander of England’s Hessian mercenaries stationed there. But Col. Johann Rall, legend has it, was so caught up in a game of chess that he never opened the letter, which was found on his body after he died in combat.

While it was never confirmed that the Hessian leader was playing chess, Weeramantry says it’s a plausible tale.

“If this had been said of a British person, I would not have believed it. The chess culture in England at that time wasn’t as developed,” says Weeramantry, a World Chess Federation master and executive director of the National Scholastic Chess Foundation. “But Germany was a whole other story. So it’s quite plausible that a German would have been playing chess. Unfortunately, they never found the chess set in the ruins of the battle.”

The story is one of many featured in “Great Moves,” a polished version of written lessons that Abrams and Weeramantry collaborated on years ago. Abrams taught chess from 1997 to 2012 at two Bronx elementary schools that went on to national championships. To add a reading component to his chess instruction, Abrams started writing brief histories of famous chess players that tied in the eras in which they played. He then sought out Weeramantry, whom he had met through a friend at the Yonkers Chess Club in the late 1990s, to analyze the moves made by the players.

Weeramantry competed internationally as a teenager and still competes today. (Following the interview with WAG, he caught a flight to Gibraltar for a tournament.) He won the New York State championship in 1975 and 2001. Four years after his first state championship, he started teaching chess at Hunter College Elementary School in Manhattan, where he established a chess program that is part of the school’s kindergarten through fifth-grade curriculum. He now oversees chess programs at more than 70 schools throughout the metro area and teaches workshops around the country.

Tying history to move-by-move chess instruction was a great concept, Weeramantry says, “because it made everything come alive. It helped capture the imagination. The kids could identify with the personalities and accomplishments of the players.”

It certainly got results. Abrams’ Bronx chess program was covered by The New York Post in 2006 after students from P.S. 291 took home first-place prizes in the K-3 and K-5 divisions at the National Elementary School Chess Championships in Denver, the school’s first, and again in 2010 when students took home another two national championships.

But after Abrams retired from spearheading the program and shifted to teaching chess privately, he says he and Weeramantry lost track of the book and efforts to have it published.

That’s where McLellan comes in. After joining Weeramantry’s scholastic chess foundation in 2014, the two were discussing projects to help spread scholastic chess when the book came up. It was a perfect fit, as Weeramantry describes it, for teachers looking for a literary or historical component to add to chess instruction.

After some polishing and additional research to broaden the historical focus — including a trip by McLellan to the Cleveland Public Library, home to one of the largest chess source book collections in the country — the book was published last year. It covers eras and players stretching back to the origins of chess as a military-inspired board game in eastern India’s Gupta Empire (circa 280-550 B.C.) with the modern game developing during the Middle Ages.

“Just like anything else, music or art or literature, you have different schools,” Weeramantry says. “You have the Romantic period, you have the Realist period, the Hypermodern period. With each, there are different movements and they align very well with movements in the arts.”

One chapter tells the life story of Paul Morphy. Born in 1837 New Orleans, Morphy was a chess prodigy by age 10 and considered among the best of his era. The book first details the story of his early childhood leading up to a breakdown of a game he played as a 12-year-old against Hungarian chess master Johann Lowenthal.

It also includes historical facts and legends, such as the Revolutionary War story, that show the many ways chess is woven into world history. The book describes how Spain’s Queen Isabella is widely credited with increasing the range of moves the queen chess piece is allowed to make. It also documents the travels of The Turk, or Automaton Chess Player. While the purported chess-playing machine actually had a human operator, it was a sensation in its time. The Turk traveled the world, vexing challengers, who included Napoléon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin.

The book should be of interest to both students and adults, Abrams and Weeramantry say. In the classroom, Abrams says, chess can have lifelong benefits. He keeps in touch with many of his chess students, all of whom went on to college and now have successful careers.

“Chess has meant a lot to them, for all aspects of their life,” Abrams says, “how they learn to think, how they learn to plan ahead. They learn to take their time and look at all the possibilities.”

And you don’t need to be a chess expert to follow along. The only assumption is that readers know the basic rules of how each piece on a chessboard moves. Weeramantry pitched the book as a great coffee table tome as well as school textbook.

“This is a game that transcends all games,” he says. “It’s an ancient game and is still going strong. So what is the appeal?”

Like a grand master, “Great Moves” reveals much of chess’ magic.

For more, visit nscfchess.org.