“There was nowhere to go but everywhere….”

– Jack Kerouac,“On the Road”

Laura Fahrenthold — like beat generation pioneer Jack Kerouac — was “On the Road” when she found purpose.

More accurately, she was face down in a pile of ashes, near her tent in the Oregon woods. The remnants of her spent campfire had just mingled with some of those of her late husband, Mark Pittman, whose urn she’d been clutching for company on the way to an outhouse when she tripped.

The shock of losing a part of Mark to a world beyond her grasp — so far from her then-Yonkers home — caused a divine idea to manifest itself: Perhaps letting Mark slip through her fingers would be a way to connect with his true nature.

The shock of losing a part of Mark to a world beyond her grasp — so far from her then-Yonkers home — caused a divine idea to manifest itself: Perhaps letting Mark slip through her fingers would be a way to connect with his true nature.

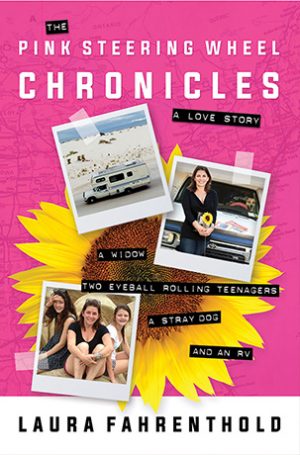

In her fearless memoir, “The Pink Steering Wheel Chronicles: A Love Story” (Hatherleigh Press/Penguin Random House) — journalist Fahrenthold, content editor at Woman’s World magazine, relives her husband’s traumatic death and the 31,000-mile road trip to healing with her grieving — sometimes eye-rolling, always up for adventure — daughters.

“It was a way to be a family again,” the Hastings-on-Hudson resident told WAG of the decision to take then 11-year-old Nell and 9-year-old Susannah on an adventure outside of their comfort zone (bringing “Mark In A Box” along for the ride). “In order for my girls to heal,” she said, “they would need a lot of love, a lot of fresh air and a lot of sunshine.”

Fahrenthold’s brutal honesty in the book is bolstered by a sarcastically wicked inner monologue that brings humor even to her most morbid thoughts and makes for an experience-packed adventure that honors Pittman’s spirit.

In life, James Mark Pittman was a big, lumbering, cowboy boot-wearing financial journalist from Kansas with an inherent sense of fairness and a fire in his belly to uncover social injustice. His early adulthood was influenced by the writings of counterculture icons like Bob Dylan, gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson and the generation-defining Kerouac. Pittman shared their “iconoclastic contempt for authoritarianism” and even embarked on his own character-defining motorcycle journey one summer in college.

In life, James Mark Pittman was a big, lumbering, cowboy boot-wearing financial journalist from Kansas with an inherent sense of fairness and a fire in his belly to uncover social injustice. His early adulthood was influenced by the writings of counterculture icons like Bob Dylan, gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson and the generation-defining Kerouac. Pittman shared their “iconoclastic contempt for authoritarianism” and even embarked on his own character-defining motorcycle journey one summer in college.

Now here was Fahrenthold, face full of ash, harboring a scheme that seemed to be communicated directly from Pittman. With newfound purpose, the family changed course, buying an old RV (nicknamed HaRVey) and set off on a four-part, multi-year journey through North America to sprinkle Pittman’s ashes. Beginning in 2010, they went from Oregon to the Montana Badlands to New Mexico’s White Sands, Arizona’s Hopi Reservation — where they gained a stray dog — Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and the Canadian-American Bay of Fundy.

Along the way, “Pittman” sailed from their fingertips off mountain tops, zip lines and horseback; hitched rides on a motorcycle, landed in the belly of an alligator and in the boots of a traveling musician. He was embedded where they went mud sliding and surfing and, pointedly, in the family’s visit to the Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C.

“…how many times can a man turn his head And pretend that he just doesn’t see?”

— Bob Dylan, “Blowin’ in the Wind”

It was Thanksgiving Eve 2009 when the award-winning Pittman suffered a fatal heart attack.

He’d been in the midst of intense media focus after predicting — and doggedly reporting — the U.S. banking system’s collapse on the heels of the subprime mortgage crisis. Working as a reporter for Bloomberg News, Pittman became hell-bent on uncovering the root of the collapse, taking unprecedented steps toward making the Federal Reserve Bank more accountable to the American people. After his requests under the Freedom of Information Act were denied, Pittman became the only reporter in history to sue the Fed.

Was it some divine coincidence, then, that his grieving family was at one point in its elaborate road trip placed in the same bike-touring group as then Federal Reserve Chairman Ben

Bernanke? Was it also a coincidence that Pittman’s favorite Dylan song, “Blowin’ in the Wind,” played at a moment Fahrenthold was desperate for his approval? During the family’s travels, Fahrenthold began to feel like maybe the conversation with her late husband continued on.

Five years after stumbling through the continent, following no particular path but that of their hearts, Fahrenthold and her daughters found Pittman’s journals from that motorcycle journey of his youth. In it, he wrote of places they had been inexplicably drawn to. Then another shock: his description of a fictional character’s death mirrored, too accurately, his own.

“Coming back to where you started is not the same as never leaving.” — Terry Pratchett, “A Hat Full of Sky”

“Coming back to where you started is not the same as never leaving.” — Terry Pratchett, “A Hat Full of Sky”

As Fahrenthold set out to navigate her revelation that “the greatest loss is what dies inside of us as we continue to live,” she found solace in the most unlikely of places — camping at Walmart. It’s where she bought the pink steering wheel cover that became what she joked was her spiritual GPS. And it’s where she began to practice her story on a changing cast of housewife-shoppers — retelling her loss until the truth of it sunk in, then allowing their sympathies to heal her. “I grieved in the arms of America,” she said. It was a foothold toward the wonder she began to find everywhere. “We are really, truly connected to people,” she said.

“It is good to have an end to journey toward; but it is the journey that matters, in the end.” — Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Left Hand of Darkness”

“I think we were done,” Fahrenthold said of their journey to Kansas that ended their final trip. “I think Mark was done. It was time. We all had to let go.”

Letting go of the material Pittman meant being able to find him everywhere else.

Was he expressed in her running toward that outhouse in the woods? Or in the deli man in Yonkers urging her to take the trip? Or in Pittman’s favorite Dylan song? Whatever it was, she knows that what she found everywhere was love.

And as she remembered the love shared with Pittman she asked, “Is it really gone or has it just changed form?”

“The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind.”

For more, visit laurafahrenthold.com.