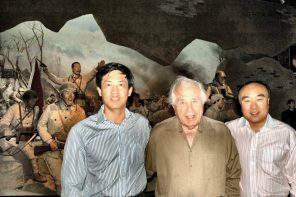

As a doctor and philanthropist, Richard Deckelbaum makes it his mission to help others.

Deckelbaum has worked in classrooms, hospitals and laboratories around the world, traveling to countries such as Zambia and Israel to help improve their public health systems. In Israel, he laid the groundwork for the world’s first medical school focused on global health and spearheaded the first children’s hospital in the West Bank. And now he shares his expertise with Columbia University students as a professor of pediatrics and epidemiology.

When asked what inspires him, he says with a smile, “(Helping people) is a part of me.”

Deckelbaum’s spirit is evident as he shows WAG the memorabilia inside his Hastings-on-Hudson home. One wall is dominated by a floor-to-ceiling display of artifacts that share space with the artwork of his wife, Kaya, profiled in May WAG. Each artifact has a story, and each of Kaya’s creations draws on ethnic influences. The objects have been collected over time, during the couple’s many trips to Africa.

Though Deckelbaum’s feet are firmly planted in the United States — in addition to being a professor, he is the director of Columbia University’s Institute of Human Nutrition, as well as a specialized pediatrician for NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital in Manhattan — much of his research is still devoted to Africa, where his career began.

As a graduate of McGill University in Montreal in the 1960s, he traveled to Zambia with Kaya to work for an affiliate clinic of the Zambian Flying Doctor Service. (The organization, later called AMREF Doctors, is now an international aero-medical service headquartered in Nairobi, Kenya.) Deckelbaum’s mission was to improve the clinic and save lives while broadening his perspective.

“I thought that before I went into academic medicine, it would be important to see things that went beyond the ivory tower,” he says.

He recalls his first day of work, which began with an eye-opening experience.

After immediately noticing that all of his 15 to 20 patients lay in dirty sheets, an appalled Deckelbaum called for change. However, he soon realized that the unsanitary conditions weren’t the result of laxity but a cultural misunderstanding. The Zambians were accustomed to sleeping on the ground — which they did — and had been soiling the sheets themselves.

“It made me realize that when traveling to a new place, a new culture, the first thing you should do is look, watch and listen, and don’t talk,” he says. “And it was after that experience, I learned that when you work in different places, you have to really understand the people and their conditions.”

A year later, Deckelbaum traveled to Jerusalem with Kaya, where he served as a liaison between the Israelis and the Palestinians as they collaborated to upgrade the Palestinian health system. That role created relationships he maintains to this day.

“A lot of my work in the Middle East is about getting people to talk to each other,” he says. “My feeling, as a doctor, is that we shouldn’t take a political stance. We should try to make things better, wherever we are.”

It was also during this time that he helped open the first children’s hospital in Israel’s West Bank, and later, co-founded the Medical School for International Health (MSIH) at Ben-Gurion University in the Negev, Beersheba, Israel. MSIH, which is affiliated with Columbia University, is the first medical school with a required four-year global health curriculum.

Deckelbaum returned to the United States in 1973 to work at Boston University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he shifted his focus to basic science while continuing to advance his overseas work.

“I’ve developed a good career in basic science and biological science, and having that career in science has allowed me to pursue other disciples, like global health,” he says. “I’m able to bridge the two by doing training in Africa, which is very exciting.”

Lately, Deckelbaum has been researching the “double burden” — the dilemma of worldwide malnutrition versus obesity — with an emphasis on Africa, of course.

“Worldwide, there’s over one billion people that are hungry,” he says. “And, there’s over one billion people that are overweight or obese because of too much food.”

At the same time, Africa is developing more so-called First World illnesses. By the year 2030, more fatalities in Sub-Saharan Africa will be caused by non-communicable diseases — such as cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, cancer and diabetes — than from malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and maternal and child malnutrition combined. His ongoing mission is to educate the public in order to reduce this likelihood.

“It’s a new era in terms of what’s going to be killing people,” he says. “Cancer, trauma, road accidents. It’s all totally unaddressed in Africa.”

He is currently working with Columbia University to facilitate the African Nutritional Sciences Research Consortium, an effort to unite the university with institutions in East Africa and conduct doctorate and postdoctoral training in basic sciences as they relate to nutrition, agriculture and noncommunicable diseases.

The objective remains the same — to save lives.

“Everyone has to learn from each other,” he says. “It’s about taking the glass that is half full and making it full.”

Kaya Deckelbaum’s artwork was recently featured in our May 2016 “Our Fling with Spring” issue. For more on her, visit wagmag.com/into-the-woods/.